Restricted growth

Multilateral action on sovereign debt must speed up

After the Covid-19 pandemic, debt crises loomed in many countries with low and lower-middle incomes. Debt levels kept soaring while international interest rates rose fast. There was reason to fear widespread sovereign defaults.

A catastrophic wave of defaults was avoided, so there was no systemic global crisis. Emerging market bond spreads are back to pre-pandemic levels. It means that interest rates are not dramatically higher than those of advanced economies, which is a sign of growing investor confidence. In recent months, Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya and Senegal have been able to issue new bonds. Since 2022, the number of sovereign defaults and requests for comprehensive debt relief has gone down. The last relevant application was Ghana’s in 2023.

It helps, of course, that the Federal Reserve and other leading central banks started to cut interest rates since March 2024. Lower interest rates mean more favourable financial conditions for countries with low and middle incomes.

Nonetheless, debt relief or at least liquidity relief will be needed in some low-income countries with deeply entrenched debt issues. Serious problems do indeed persist. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), around 15 % of low-income countries are still in debt distress and another 40 % are at high risk of such distress.

Not only default spells trouble

Even when a country does not default, debt problems tend to stifle its development. Even if the economy is still growing, national budgets stay strained because of unexpectedly high interest-costs and increasingly unstable exchange rates. Moreover, illiquid debtors are at risk of default even if they are solvent in principle. That means they may become unable to fulfil an obligation in time even though they would be able to do so with some delay.

Helping countries that are at risk of a liquidity squeeze but have sustainable debt levels should now be a priority. Failure to act fast and effectively now means more difficult and more expensive action will become necessary in the future. Solving the problems fast will facilitate investments and growth. Continuous insufficient debt rollovers always require long negotiations and come at huge economic and social prices.

According to IMF data of late 2023, the median low-income country was devoting over 14 % of its revenue to servicing foreign debt. A decade ago, the share had been only six percent. The IMF reckoned that these countries’ near-term debt repayments would reach approximately $ 60 billion per year. From 2010 to 2020, the annual average was $ 20 billion. These figures mean that poverty cannot be tackled and building climate resilience looks utopian.

A growth-focused approach is urgently needed. Low-income countries cannot tackle adverse shocks the way that advanced economies do. In the Lehman Brothers crisis (2008–2009) or during the Covid-19 pandemic (2020–2021), high-income countries responded with temporary expansionary policies that were funded with massive borrowing and reversed once stabilisation was achieved. Moreover, social-protection systems reduce the down-ward spiral that the loss of wages means. Low-income countries lack those means to escape crises.

Valid steps in the right direction

The good news is that the international community is making progress regarding how to handle excessive sovereign debt. In November 2020, the G20 adopted its Common Framework for Debt Treatments (CF). It is a multilateral mechanism for restructuring and forgiving excessive sovereign debt. It does not suffice for resolving all current issues, but it has positive features:

- It is creating a coordinated multilateral debt renegotiation framework at a time in which the geopolitical system is fragmenting.

- It involves all relevant private, statal and multilateral creditors rather than only the Paris Club which represents the bilateral creditors of the established economic powers like the G7. China and other emerging-markets creditors are involved in the CF. That is a fundamental step in the right direction. Building trust and agreeing on rules among so many different types of creditors is difficult, of course, and will take time.

- The CF is a fundamentally sound initiative given that the international community has been unwilling to define a legally binding mechanism to handle sovereign debt problems. In this setting, the CF is a valid second-best soft-law approach. At this point, no alternative is in sight.

- The CF can and should be developed further. So far, it only applies to low-income countries, though some middle-income countries are struggling with serious problems too. Moreover, it would make sense, for example, to add a mechanism to provide temporary liquidity relief to countries in need. A clear and fast liquidity channel would allow those countries to avoid the stigma of debt restructuring and stimulate participation.

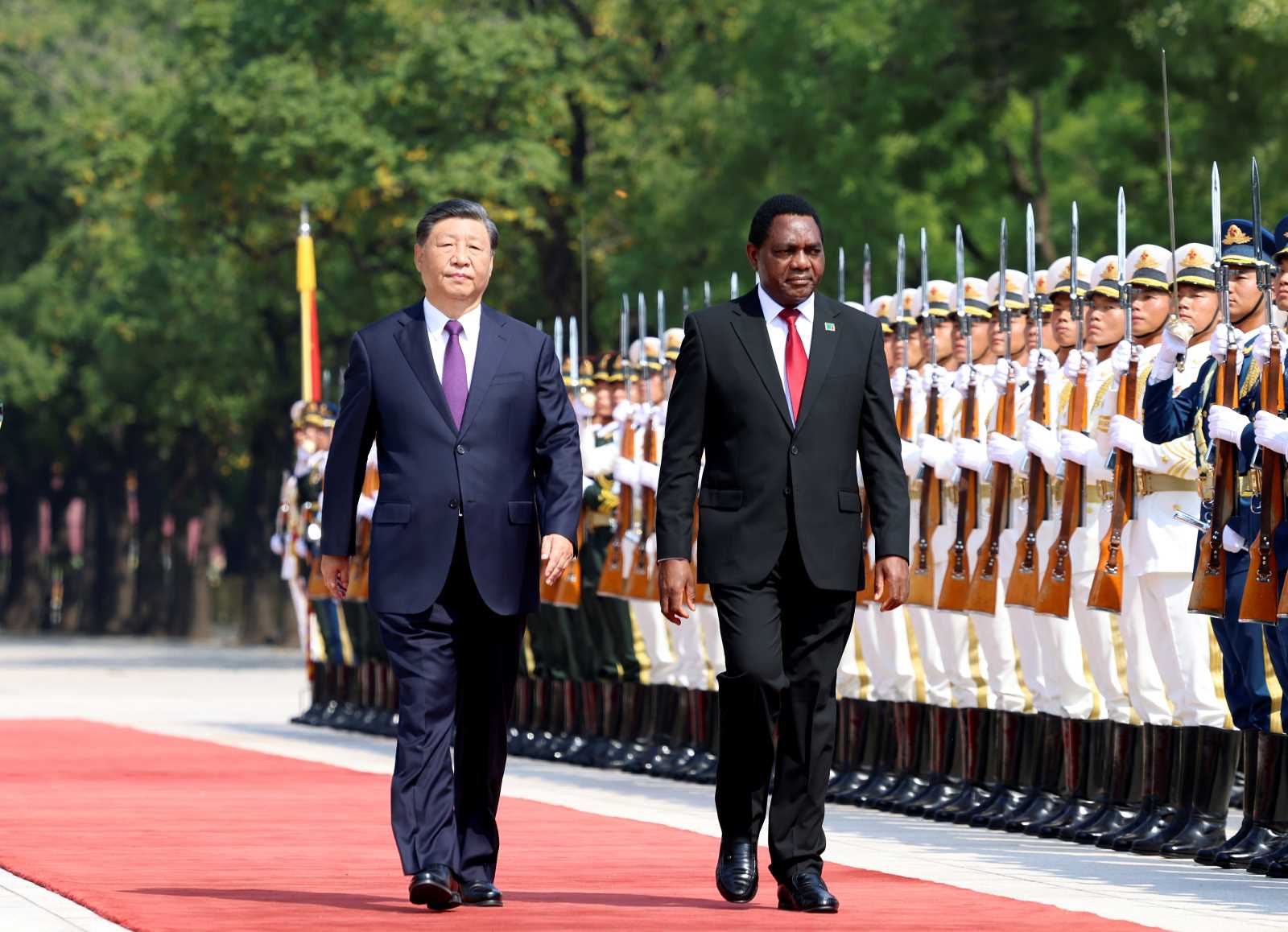

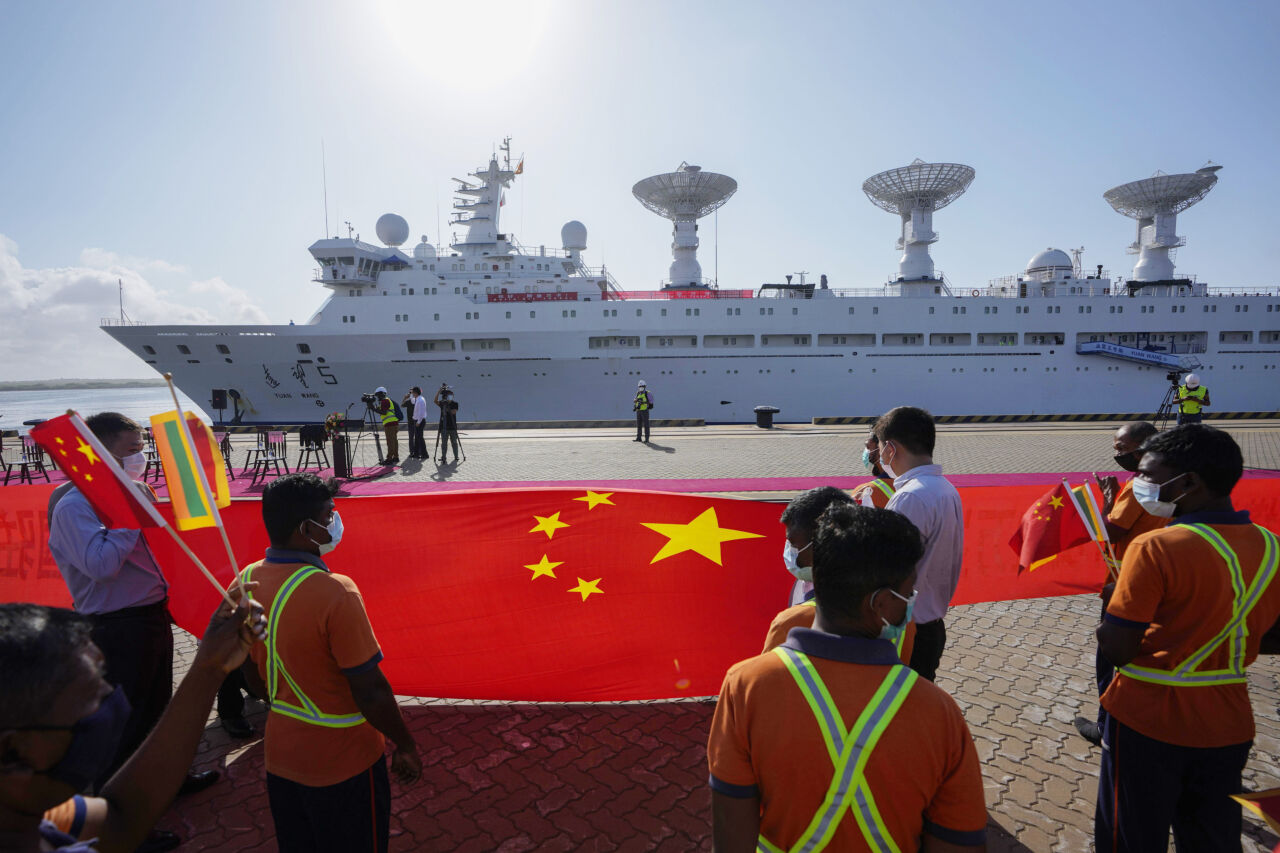

Decisive progress depends on cooperation of Paris Club donors with emerging markets, and especially China (see box). It is difficult in a period of polarisation, but the fact that the CF exists and is developing reasonably shows that it is possible.

Picking up speed

CF procedures are slow, but they are gradually picking up speed. Negotiating Ghana’s agreement took roughly half the time it took for Chad’s in 2021 and Zambia’s in 2022.

Though the CF does not formally apply to them, the cases of the middle-income countries Suriname and Sri Lanka were dealt with according to its rules too. Sri Lanka was the second case, and it proceeded faster than the first.

The general trend is that parties are becoming more familiar with the process. They increasingly know what to expect, are building trust and learning to overcome stumbling blocks. Approval in principle for programmes will soon enable the IMF to disburse support as it receives the required financing assurances, but before every detail is hammered out.

In 2023, the G20 established the Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable (GSDR) in cooperation with the IMF and the World Bank. It is a useful forum for discussing technical issues, methodologies and implementation issues. As in the CF, all relevant parties are involved.

In another important step, the CF has embraced the principle of comparable treatment of commercial and bilateral lenders from the Paris Club as well as non-Paris-Club countries. However, a clear definition of “comparability” that would suit all restructuring models has not been found yet.

Private bondholders are an increasingly important group of creditors. So far, however, they were only brought in at the end of CF debt negotiations. The big challenge is that none of the three principal creditor groups likes to proceed with its own settlement without knowing what terms the debtor agrees with the other groups. The GSDR should address that official and private creditor processes move in parallel.

Progress is being made, but more is needed – and the faster it happens, the better. The CF is useful, but not really fit for purpose yet. A core challenge is that countries that need CF support often hesitate to apply for it. The reasons include that they are not assured that they will get significant debt restructuring or renewed access to financial markets. Moreover, there is a stigma attached to turning to creditors and asking for a renegotiation of loan conditions.

José Siaba Serrate is an economist at the University of Buenos Aires and at the University of the Centre for Macroeconomic Study (UCEMA), a private university in Buenos Aires. He is also a member of the Argentine Council for International Relations (CARI).

josesiaba@hotmail.com