Sovereign debt

Zambia’s difficult quest for debt restructuring

In June 2024, Zambia’s finance ministry announced that more than 90 % of holders of its outstanding international bonds had accepted its restructuring proposal. The bonds’ nominal is worth $ 3 billion, and the deal was an important step towards the comprehensive debt restructuring Zambia needs.

The southern African nation’s sovereign debt now amounts to about $ 27 billion, which includes the obligations that have not been met in the past four years.

The debt mountain results partially from governmental mismanagement, but the problems were severely worsened by global trends. The impacts of the climate crisis are getting worse, for example. Moreover, the Covid-19 lockdown not only hit Zambia’s domestic economy, but the international slump depressed the copper price. Copper is Zambia’s most important export good. The very low commodity price meant that government revenues dropped fast in a time of desperate need when more government spending was necessary. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), sovereign-debt problems have been escalating in many places for reasons like this.

Long, difficult and cumbersome

The Zambian government’s quest for debt relief has been long, difficult and cumbersome. A core problem is that many different stakeholders had to be brought on board. Since their interests diverge, the G20’s “Common Framework on Debt Treatment” did not work out well. Important stakeholders include:

- international financial institutions like the IMF and the World Bank,

- bilateral agencies from high-income countries which belong to the Paris Club of long-established creditors,

- bilateral agencies from China and other emerging markets that do not adhere to the Paris Club and

- private bondholders.

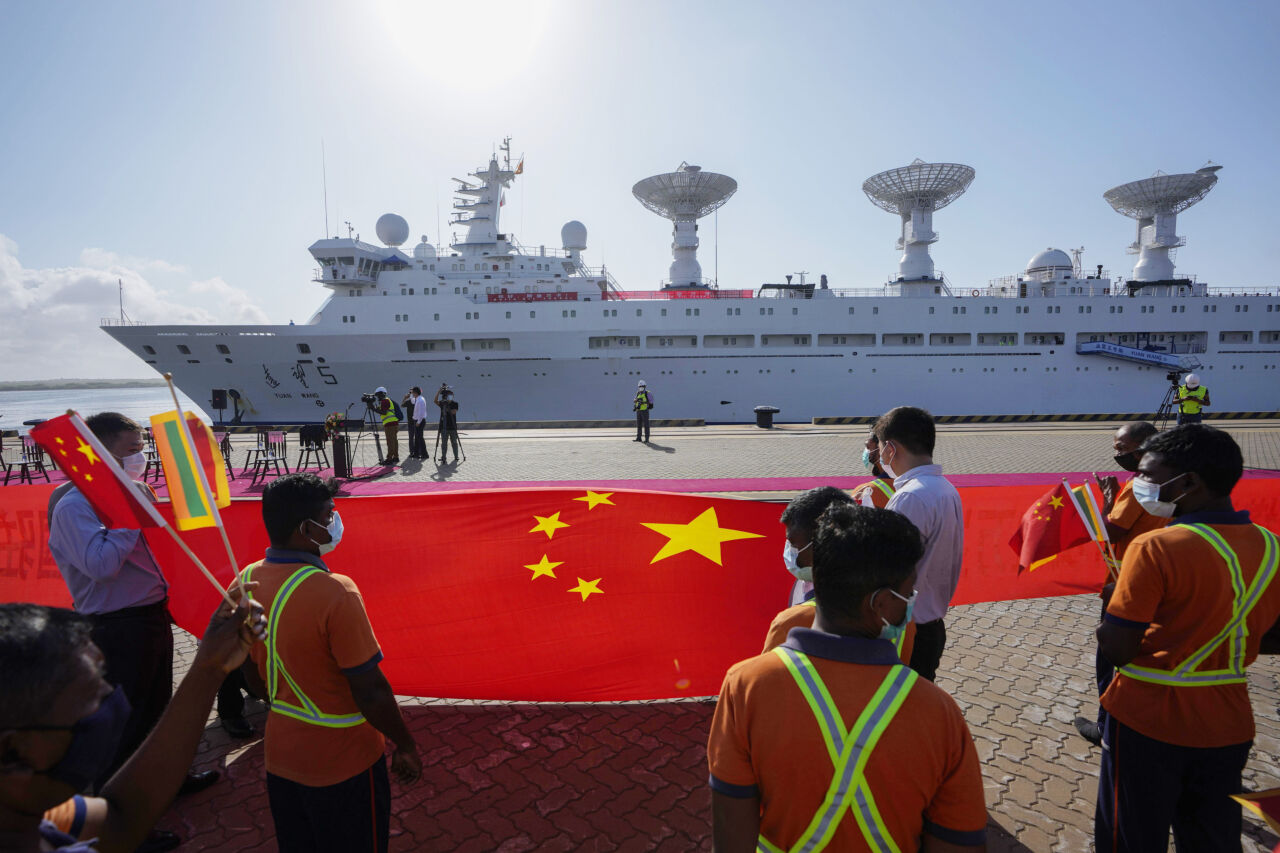

Adding to the worries, Zambia’s government must yet reach an agreement with the commercial banks that it owes money. That may well prove difficult again, not least because they are based in different countries with different political cultures. As the experience of other countries shows as well, debt restructuring has become even more difficult than it was around the turn of the Millennium. Sri Lanka is a prominent example.

Since the default in November 2020, Zambia’s economy has been in serious crisis. As arrears piled up, the debt mountain kept growing. Quite obviously, debt restructuring was needed to get the economy going again.

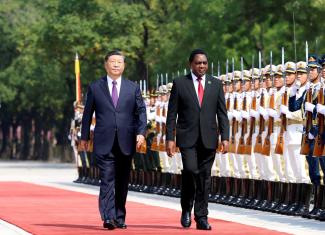

President Hichilema’s mission

President Hakainde Hichilema took office in August 2021, after winning a general election. His top priority was to secure better terms for Zambia’s debt obligations and reduce its debt-to-GDP ratio.

The IMF proved supportive. In August 2022, it approved an emergency loan of $ 1.3 billion. Though this loan increased the debt and led to austerity, it did enable Zambia to implement reforms. It also obliged the government to agree on a debt-restructuring plan with its creditors.

It took Hichilema almost a year to reach a restructuring deal with the long-established “official creditors”. These include:

- multilateral institutions like the IMF,

- bilateral donors such as the USA and the EU countries, which all belong to the Paris Club and

- bilateral agencies from emerging markets.

Zambia, however, only owed them $ 6.3 billion. The deal rescheduled repayment over 20 years, starting with a grace period. All summed up, it basically means that, instead of having to return $ 6.3 billion within 10 years, the country’s debt servicing costs will only amount to $ 750 million in that period, on average $ 75 million per year.

The deal postpones debt payments and reduces interest rates, but it does not cancel debt, as was the case with debt relief two decades ago. What will happen after the next 10 years, is an open question. All parties concerned hope that growth will pick up strongly, so the country will be able to bear the debt burden in the long run. If its performance improves above expectations, interest rates, for example, will rise again, though details would still have to be defined. The downside could then be that tougher debt-serving would stall growth once more.

Getting bondholders on board

After this agreement, the Hichilema government had to get other creditors on board. It did not go smoothly.

Indeed, there was a serious setback in November 2023. After Zambia’s negotiators concluded an agreement with the holders of the above-mentioned Eurobonds, bilateral creditors objected. Chinese agencies played an important role in arguing that private bondholders were getting a better deal than governmental institutions. Other bilateral creditors insisted on the principle of comparable treatment too. According to it, all creditors must share restructuring burdens fairly.

Zambia’s government thus had to find a compromise that would satisfy all parties. Earlier this year, Zambian officials travelled to China. They discussed debt issues with various parties, including the Export-Import Bank of China and Chinese commercial banks. In February, President Hichilema announced that China and India had finally agreed to sign memorandums of understanding (MOUs) on restructuring Zambia’s debt. He had thus managed to bring the two final bilateral creditors on board.

This step then paved way for accelerated negotiations with Eurobond holders, and a deal could be sealed in the summer. It is in line with the demands of all official creditors. The repayment period has been extended by at least eight to fifteen years. Unlike the multilateral and bilateral creditors, the bondholders have accepted a “haircut” of 25 % or so. Haircut is the term financial investors use for the reduction of a bond’s value. They accepted the deal because they will be paid higher interest rates than the official creditors and get their repayment sooner.

The numbers are not completely fixed. If Zambia’s economy performs better than expected repayment conditions for bondholders will be more favourable. The IMF is the arbiter and will decide whether expectations have been exceeded. The risk, of course, is that higher debt-servicing costs might then hamper economic growth in Zambia again.

Improved outlook

Zambia’s agreement with Eurobond holders certainly represents a critical milestone towards restoring debt sustainability. As attention must now turn to the commercial creditors, it is helpful that the Eurobond deals roughly outline what the final deal must look like.

The good news is that Zambia’s economy has begun to pick up speed again. The progress made on debt restructuring has renewed investor confidence and enhanced the country’s attractiveness. The government reckons that accounting for inflation and other long-term factors, its total burden of debt plus interest rates will actually be reduced by 40 %. As it is set to spend considerably less money on debt servicing in the next 10 years, so its fiscal space is growing decisively. It will be able to spend more on education, health and infrastructure, and to the extent that it manages to stem corruption, it may even be able to avoid painful austerity.

The road ahead, nonetheless, may still prove rocky. The remaining commercial lenders include the Chinese state-owned China Development Bank and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China. Together, Zambia owes them more than $ 900 million, and to them, geopolitical concerns may matter again. Other important players are private-sector entities like the multinational African Export-Import Bank or the London-based Standard Chartered. To finalise the debt restructuring process, all of these institutions must agree to terms that are comparable to those concluded with bondholders and official bilateral creditors.

Beaulah N. Chombo is a Zambian economist and analyst.

beaulahchombo27@gmail.com

Charles Chinanda is a Zambian economist and analyst.

charleschinanda@gmail.com