Protests

Too much violence and grief

Since 2019, Human Rights Watch’s annual World Reports have documented patterns of increasing state repression in East Africa. Tanzania and Uganda remain highly restrictive, with governments regularly suppressing freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and dissent. In May, for example, two prominent activists made headlines when they were detained and tortured by Tanzanian authorities for days after they entered the country to express solidarity with imprisoned opposition politician Tundu Lissu. Both Boniface Mwangi, who is from Kenya, and Ugandan activist Agather Atuhaire reported that they had been sexually assaulted, which the Tanzanian police denies.

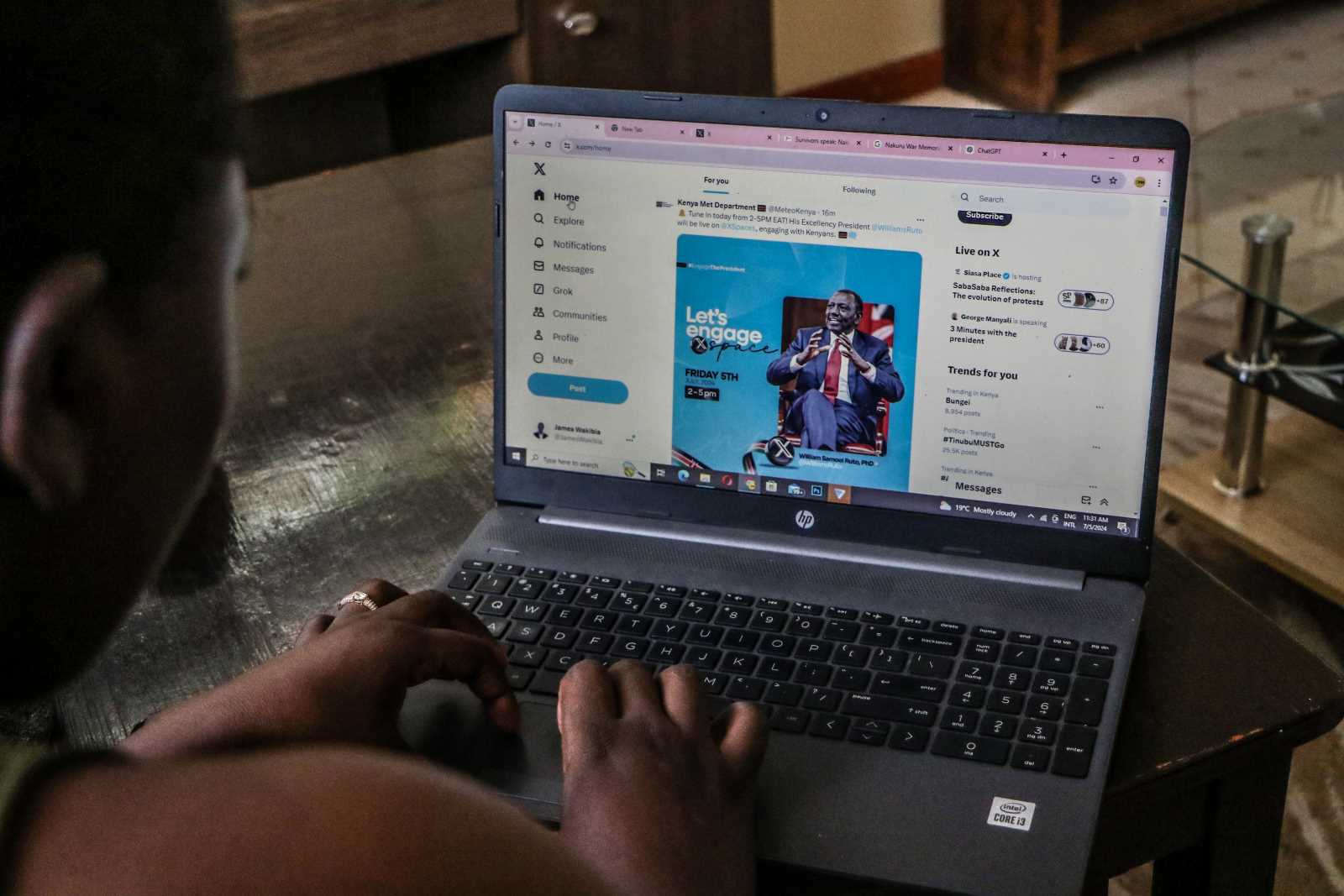

In Kenya in particular, state repression and violence are once again being carried out in response to the protests that have engulfed the country over the past 12 months. In 2024, the so-called “Gen Z protests” in Kenya attracted international attention. Young people organised against the government’s controversial finance bill, which would have imposed drastic new taxes on an already struggling economy. Their movement achieved a partial victory when the government agreed to withdraw the bill. However, this success came at a high price: dozens of people were killed across the country and hundreds were injured, though the exact numbers are difficult to verify. Even the Kenya Defence Forces were deployed to support the National Police Service. Many people have been reported missing.

This tragic death toll in protests is nothing new in Kenya’s political history. Protests have always been a central part of the country’s civil society, from its anti-colonial struggles to the movement for multi-party democracy in the 1990s. But repression has also been a constant. After the disputed presidential elections of 2007–2008, the police cracked down brutally, killing over 1200 people and displacing hundreds of thousands. After the 2017 elections, violent riots broke out again, leaving at least 97 people dead, many of them in opposition strongholds. Dozens of women and girls reported sexual assaults. Journalists and human-rights activists who exposed such violations were arrested, threatened and attacked.

More recently, in 2023, opposition leader Raila Odinga called for demonstrations against the government of President William Ruto.

The protests resulted in at least 30 deaths, many injuries and property damage. In June and July of this year, as Kenyans marked the anniversary of the Gen Z protests with new nationwide demonstrations to honour the dead and renew their demands, at least 42 people were killed and hundreds injured. Several cases drew national outrage, including the filmed fatal shooting of an unarmed street vendor.

The pattern is familiar: every new wave of protests is announced as peaceful. But when the tear gas clears, people have been killed, families are mourning and property has been destroyed. Young people are at the centre of this reality. They are driven to activism by disappointment in politics, the rising cost of living and unfulfilled promises of democracy.

Why do these protests so often escalate into violence?

Several factors contribute to the outbreak of chaos. One is infiltration by criminal elements and opportunistic looters, especially in urban centres such as Nairobi and Mombasa, where criminal groups use the protests as a cover to rob and destroy property. Citing these threats, the police respond with force, but are often unable to distinguish between criminals and legitimate protesters.

At the same time, an alarming suspicion has been raised: activists and observers point to “unknown groups” that incite violence but are never clearly identified or prosecuted, fuelling speculation that elements within the security services themselves may be stirring up chaos to discredit the protests.

Moreover, police accountability remains notoriously weak. Investigations into deaths during protests rarely lead to convictions. This impunity further erodes public trust.

As political scientists have emphasised, violent resistance is generally not as effective as nonviolent action in achieving long-term goals. This poses difficult questions for Kenyan activists. If protests are likely to be met with deadly force, do organisers bear moral responsibility for the suffering inflicted on their supporters? Should they reconsider their tactics in light of the predictable cycle of state violence and social unrest?

East Africa needs new approaches. Civil-society leaders should think creatively about safer, less confrontational ways to exert pressure: legal activism, digital mobilisation, community organising and building transnational alliances. These forms of resistance are an effective way to mobilise public support and can be more difficult for authoritarian states to suppress.

State actors must also take action. Harsh rhetoric such as that used by President Ruto, who called on the police to aim at the legs of demonstrators during the recent protests, must be toned down. Kenya was one of the first African countries to develop a national action plan for youth, peace and security, but its implementation has focused mainly on tough security measures and has neglected important aspects like prevention and protection. State actors should maintain open channels for genuine dialogue with young people, raise public awareness of existing complaint mechanisms and invest in psychological care and social support for communities already traumatised by repeated raids.

The citizens of East Africa are demanding better leadership and an end to the bloodshed. Responding to them with violence is not only immoral, but also unsustainable. The future of the region depends on breaking this deadly cycle.

References

Kaplan, S., 2022: Nonviolent protesters and provocations to violence. Washington University Review of Philosophy: The philosophy of war and violence, Vol. 2, 170-187.

Grace Atuhaire is a Pan-Africanist, Social Development and Communications Specialist and a PhD candidate in Political Science at the Eberhard Karls University Tübingen.

graceseb@gmail.com