Protests in Kenya

“I am plagued by doubts about how we as a country can survive”

I went to the demonstration on 25 June with a certain sense of hope. That day marked the first anniversary of the storming of the Kenyan parliament, the climax of the youth-led protests against the government in 2024. I hoped that at least the families of those who had died in the previous year’s protests would be one step closer to justice and coming to terms with the loss of their loved ones.

We wanted to march through Nairobi, lay flowers at various places where protesters had been killed to commemorate them, and then go to the final stop in front of the parliament building, where we wanted to hand over a petition to the speaker of parliament to push for a faster trial so that those responsible would be prosecuted and the families would receive some kind of compensation from the state for their loss. We wanted to submit the same petition to the president’s office.

The police had made things very difficult for the families and their planned demonstration before finally announcing that a peaceful march could take place. Many people came to the city that day – mothers and fathers, relatives of the victims and numerous Kenyans who had come out of solidarity, despite the roadblocks on the main streets and the barbed wire surrounding the parliament and government buildings.

I personally started the day alongside Mama Rex, Mama Kennedy – two women who lost their sons in last year’s protests – and former Chief Justice David Maraga, keeping my fingers crossed that the state would, for once, allow us to commemorate our heroes. But we had barely walked what felt like 100 meters when tear gas canisters were thrown at us, followed by rubber bullets; and so, the chaos began. Water cannons were also used, and live ammunition was fired. I spent the rest of the day among protesters in various parts of the city, trying to get to the parliament and helping injured people, until I gave up in the evening and found my way home. As darkness fell, gangs of thugs looted and destroyed shops and attacked women who had joined the protests. When I got home, I was physically exhausted – but above all mentally and emotionally drained.

At least 19 people were killed that day. I spent the following days helping victims, offering my condolences to the families affected – and, as always, demanding justice.

Saba Saba

Almost immediately, discussions about Saba Saba began. The original Saba Saba protests on 7 July 1990 were a key moment that helped bring about multiparty democracy in Kenya. To this day, Kenyans take to the streets on 7 July (“Saba” means seven in Kiswahili) to demonstrate for their rights. This year, tensions in the lead-up to the anniversary were running higher than ever.

I made a deliberate decision to stay away. We needed to organise ourselves better. I felt that the loss of life, the injuries and the damage were becoming too great, and that the state had repeatedly shown that it was prepared to treat its citizens with unlimited brutality. On the evening of 3 July, I entered my house and did not leave until the morning of 9 July.

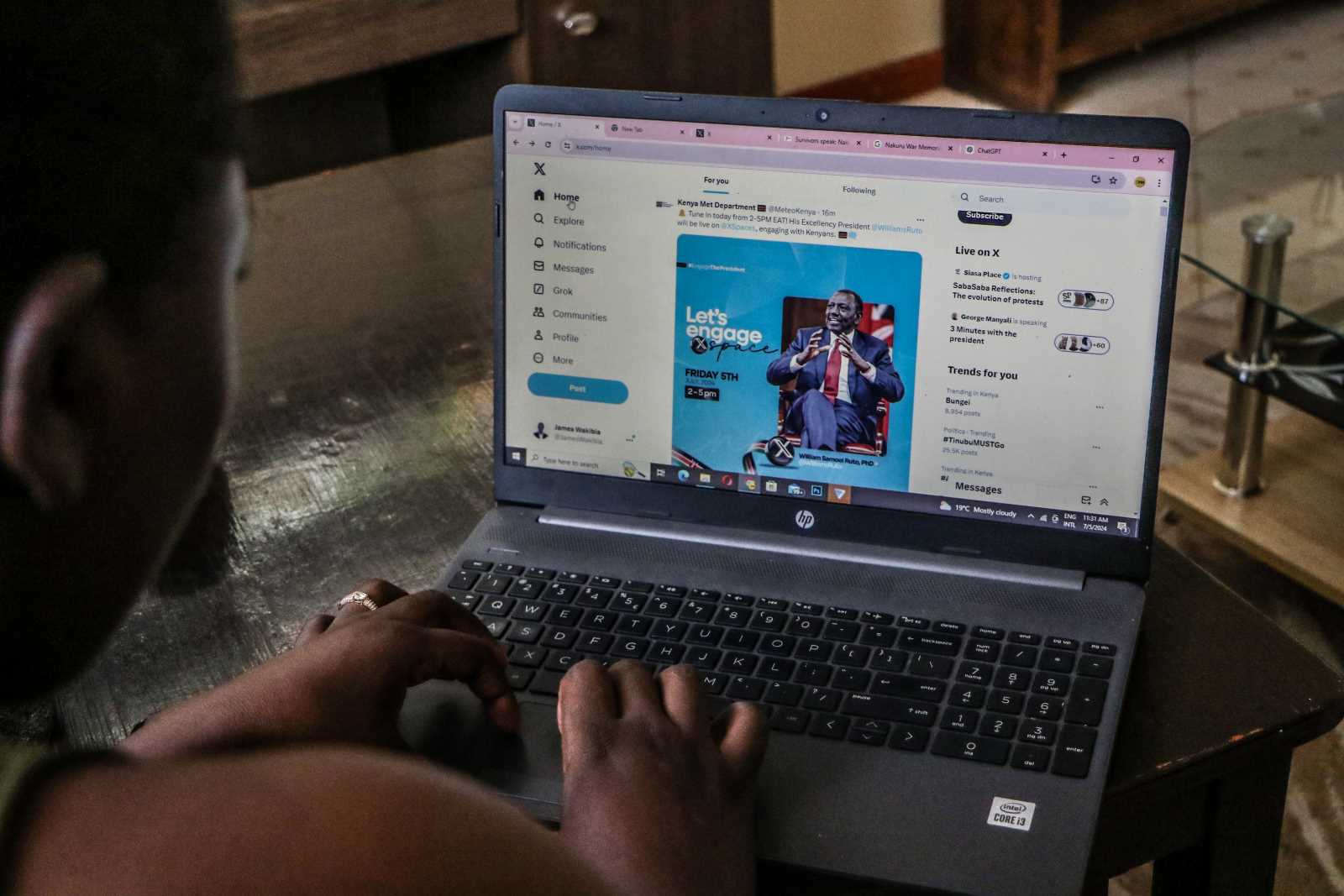

I passively watched online as people made plans for Saba Saba, while I prayed at home for my sanity and the salvation of my country. I tried to take time off, rest, and not be particularly productive. 7 July arrived, and the state panicked. It had literally sealed off the city. It was almost comical as a reaction to a group of unarmed youths. No one is going to die today, I thought – until we saw posts online showing the police spreading terror in smaller towns and residential areas all over the country.

I have a relative who runs a small private clinic in Ngong town. On that day, 12 victims with gunshot wounds were brought in, and even the paramedics were traumatised by the events of the day. By nightfall, the death toll had risen to 30, and it has now reached at least 42 as more victims have succumbed to their injuries.

Autopilot mode

Since then, I have been almost in autopilot mode. I am concerned about my personal safety and that of my family. I feel that I am not there for my son as much as I would like to be. I am tired and sometimes I want to give up. I am not sure what we as citizens can do to bring about the urgently needed changes more quickly and with less damage. Not long ago, I officially joined the political committee of former Chief Justice Maraga’s presidential campaign. As I settle into my new role, I am plagued by doubts about how we as a country can survive until 2027, when the next presidential election is scheduled to take place.

Much has changed since last year. It now seems clearer than ever that the government has decided to declare war on its predominantly young population. The death toll from state-sanctioned brutality continues to rise. People are disappearing without a trace. Since last year, bodies with undisclosed causes of death have been found in garbage dumps, rivers and other locations throughout the country.

At least 20 people have died in police custody in recent months, according to the Independent Policing Oversight Authority, including teacher and blogger Albert Ojwang, who was abducted from his home and taken to the central police station in Nairobi for criticising a police boss online.

In mid-July, Kenya's most prominent activist, Boniface Mwangi, was arrested on fabricated charges. Boniface's prominence is drawing a lot of attention to the case, but many more young people – some of them minors – have been held in Kenyan prisons for weeks. Many are charged with terrorism, and their bail is set so high that their families cannot possibly pay it. I am currently helping to coordinate a national fundraising campaign to find lawyers who will work pro bono and to pay the bails.

Shoot to kill

Boniface Kariuki was shot at gunpoint while selling masks during a protest. It feels like everyone has the video of his execution on the phone. It is not even necessary to demonstrate to fall victim to violence: Bridgit Njoki, a 12-year-old girl, was hit by a stray bullet during the Saba Saba protests while watching television at home. Many more young people, including children, have been injured in the violence surrounding the protests. This was to be expected: In June, Interior Minister Kipchumba Murkomen ordered the police to shoot to kill. In July, President William Ruto replaced Murkomen’s orders with a public announcement that the police should aim for legs. In addition, it seems that gangs of thugs were hired to infiltrate the protests and harass and attack citizens.

The government also appears to be paying media outlets and bloggers to spread propaganda and narratives that seek to confuse the people. On 25 June, the Communications Authority of Kenya issued an order banning live coverage of the ongoing protests on national television. Four Kenyan filmmakers were temporarily detained in May for allegedly being involved in the production of “Blood Parliament,” a BBC documentary about state violence in connection with the 2024 protests. Rose Njeri was arrested for creating a website that facilitated public participation against the government’s finance bill. People like me, who are at the forefront of the fight against the government, have to take special precautions to ensure our personal safety. Personally, I no longer feel safe when I am out at night.

More desperate than last year

Kenya is on a dark path. What frustrates me in particular is that Member of Parliament Kimani Ichung’wah who belongs to the ruling United Democratic Alliance (UDA) openly admitted that many of the financial bill proposals we protested against last year were passed quietly. Opposition leader Raila Odinga has once again cooperated with the government in a major plan. This leaves us with no official opposition - and we have a vice president who was technically appointed illegally, as he took office in the absence of an Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) board.

There have been several attempts to pass outrageous laws, such as one to extend the president’s term of office from five to seven years and others aimed at restricting social media or the right to demonstrate. The government has been reshuffled several times, and the president has appointed several more advisers.

As a movement, we feel like we are constantly putting out fires while this regime bombards us with one problem after another and simultaneously plans how to stay in power and amass more wealth. Many Kenyans are angrier or more desperate about the state of their country than they were a year ago.

By the way, I also don’t understand why international institutions and governments continue to interact with our government representatives and shake their hands. I personally attended a meeting with the Dutch royal family, which took place despite a petition with over 22,000 signatures from Kenyans urging the royal family to cancel their trip considering human-rights violations in the country. The Dutch royals then agreed to meet with us as a movement. The whole thing was a PR stunt and quite a disappointment. Following this meeting, no tangible efforts were forthcoming. Such behaviour is not limited to Kenya: the world seems to be standing by and watching as Palestine, the DRC, Sudan, Haiti and many other countries suffer without anyone actively working for justice. We accept that no one will come to save us, but we at least hope that the world will not hinder us by supporting a repressive regime.

Remaining strong

So, things look pretty bleak at the moment, with little hope in sight. However, I find strength in how Kenyans continue to stand up for one another – from hospital bills and blood donations to requiem masses and funerals. Despite all the threats to our lives, we still take to the streets. Moreover, a growing number of Kenyans seem to realise that it is up to us to save ourselves. We all have a role to play if the people who are supposed to protect us are so clearly against us. The government continues to try to portray us as anarchists and enemies of progress, while hypocritically courting Western favour. But we continue to receive expressions of solidarity, especially from other African countries such as Togo, Burkina Faso and Zambia.

The best way forward currently seems to be through elections. We are organising to bring about a change in leadership and take political power. From social-media posts to political education to rallies, we are committed to changing the way Kenyans participate in politics. We cannot keep electing the same old, tried and failed politicians and expect different results.

We also cannot afford to be indifferent and fail to engage in governance as we have done in the past. In the last election cycle, nearly half of eligible voters did not participate in the elections. This must change. We are traveling across the country encouraging citizens to arm themselves with their ID cards and voter registration cards and, when the time comes, to choose their leaders based on their merits and past achievements. Most importantly, the vigilance toward what is happening in government that was awakened last June must remain strong – no matter how hard the government responds.

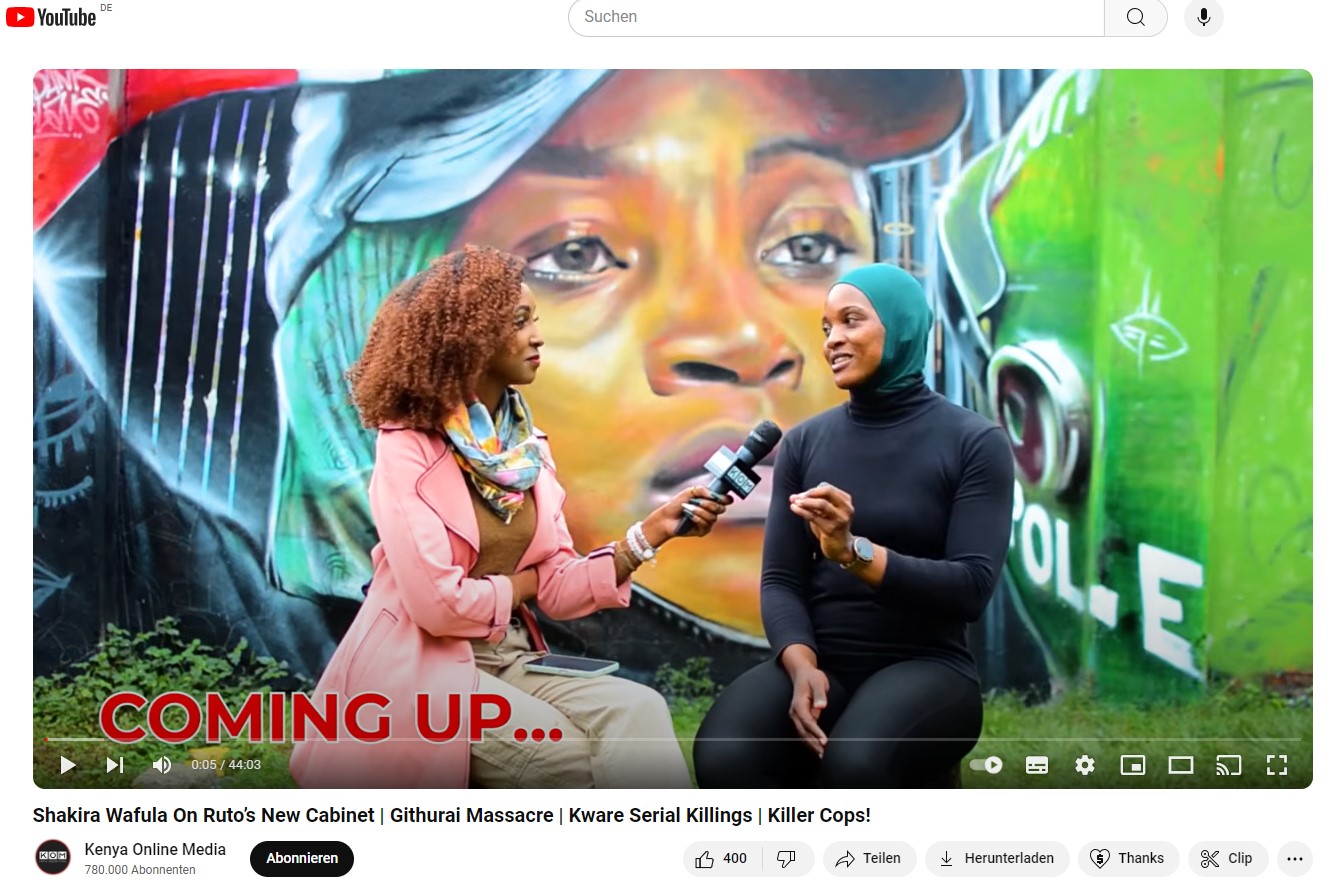

Shakira Wafula is a sports science student and an active citizen.

sfitermined@gmail.com