Global governance

How to improve the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatment

Responding to the pandemic shock in 2020, the G20 (group of 20 largest economies) implemented the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) in support of low-income countries. From May 2020 to December 2021, the 73 eligible countries neither paid interest nor repaid their debt. In total, the suspended payments amounted to $ 12.9 billion.

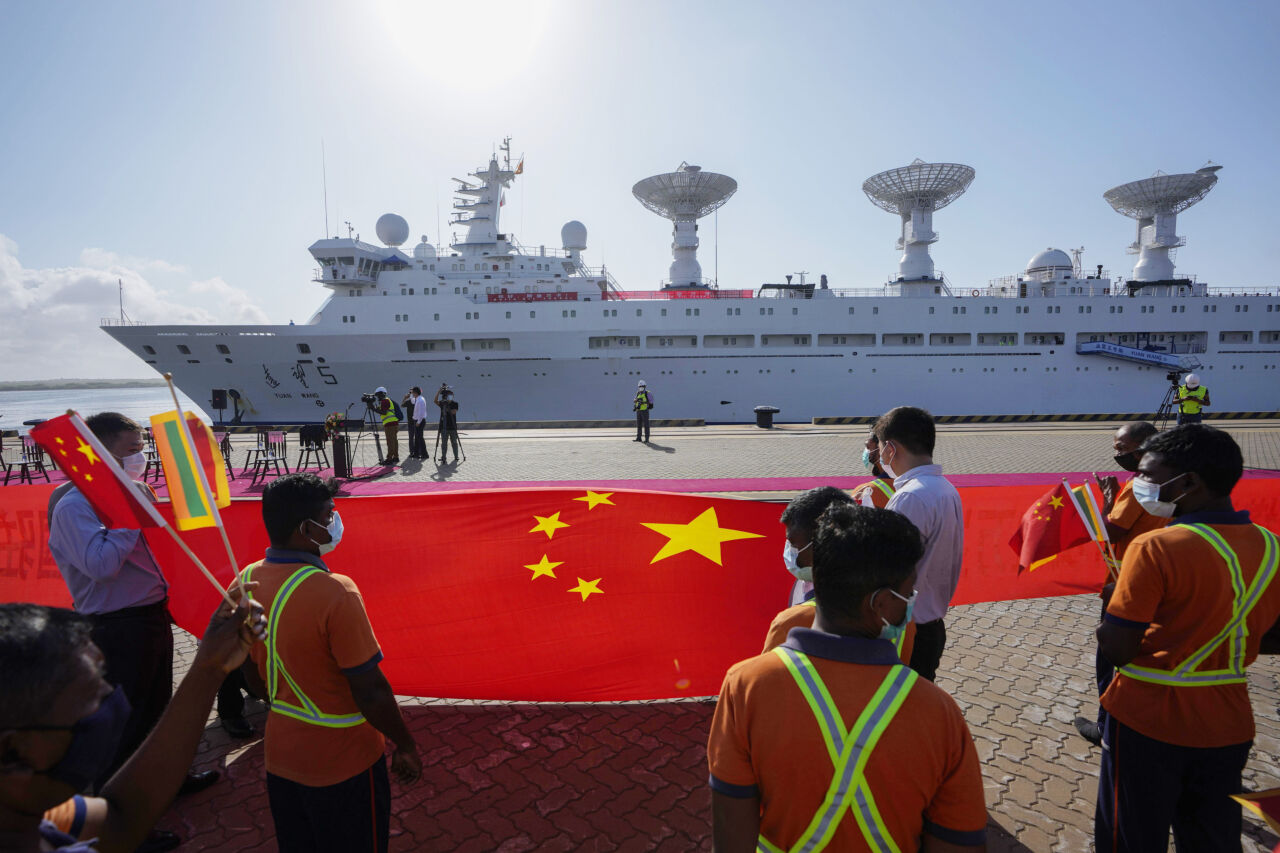

The DSSI was quite helpful, but it did not solve longer-term problems. In 2022, the world’s poorest countries had to afford $ 35 billion in debt-service payments, according to the World Bank. They owed the money to multilateral, governmental and private institutions. More than 40 % was owed to China, now the world’s largest bilateral creditor.

The Common Framework for Debt Treatment

In view of mounting problems, the G20 launched the Common Framework for Debt Treatment (CF) to reach beyond the DSSI. It is the only multilateral mechanism for forgiving and restructuring sovereign debt. An international mechanism to deal systematically with sovereign insolvency would be better, and Germany’s Federal Government deserves praise for endorsing the idea.

So far, however, the CF is what we have. It has not achieved much. Only three countries – Chad, Ethiopia and Zambia – have applied for debt treatment under the CF, and none has accomplished debt restructuring.

More must obviously happen. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), 60 % of low-income countries were deemed to be at risk of – or already in – debt distress at the start of 2022. That was twice the level of 2015. Rising interest rates, moreover, are further reducing governments’ fiscal space (see André de Mello e Souza on www.dandc.eu).

The implication is that the governments concerned cannot respond assertively to the polycrisis that humankind must rise to. Failure to act fast, however, means more difficult and more expensive action will become necessary in the future. The CF is not the problem-solving mechanism the international community needs today – it mostly remains a vague promise.

The way forward

It would make sense to enlarge the scope of the CF. Many middle-income countries are struggling with debt problems too. They must not suffer protracted liquidity problems or even insolvency.

So far, moreover, both DSSI and the CF only deal with governmental bilateral claims. This is insufficient as loans from private-sector creditors matter very much. Private financiers must be involved in debt restructuring. Otherwise, burdens will not be shared fairly and the temptation to “free ride” will stay strong, with relevant players trying to benefit from joint action without contributing to it.

Clear guidelines are also needed for the CF’s cooperation with international financial institutions. It would be useful, for example, if the IMF declared that its emergency lending to governments in arrears regarding private and bilateral loans will continue even when those governments ask for restructuring and start good-faith negotiations with the CF and other creditors.

Involving the private sector

In such a setting, moreover, the G20 could recommend generalised debt-service suspension while restructuring negotiations are going on. That would apply to private-sector loans too and thus serve as incentive for broad-based participation in the process.

A strong point of the CF is that it unites members of the Paris Club with other creditors, especially China. The Paris Club is an organisation in which established donor governments coordinate their response to sovereign debt problems. So far, Brazil is its only emerging-market member. It would be good if all G20 members that are engaged in lending to foreign governments joined the Paris Club.

The CF could then become a mechanism for involving and coordinating the entire range of creditors in the restructuring processes, including private-sector financiers in particular. Unfortunately, the CF still lacks a mechanism to stimulate their participation.

This lack is counter-productive, since all creditors, and not only CF members, deserve equal treatment. The CF also lacks proper methods for comparing various creditors’ claims and obligations.

Comparability and transparency

Assessing comparability is a challenging task. The range of creditors that lend to sovereign governments is very broad. It includes governmental, semi-governmental and private lenders. They operate according to different laws and use a broad variety of instruments. There is a great variety of contractual agreements. Moreover, some credits are granted at market rates while others are concessional.

Compounding the problems, not all contracts are disclosed to the public. Efficient sovereign debt-restructuring has to surmount a complex chain of hurdles to ensure the burden is shared equitably.

The current scenario is not transparent, however, which makes coordination of creditors very difficult. Holdouts have plenty of opportunities for obstruction, and free riding is hard to prevent.

More debt transparency is therefore needed. Debtors as well as creditors should have the obligation to disclose all relevant information to a trustworthy international agency, which might be hosted by an international institution like the IMF. The information would include all loans and cover amounts, terms, guarantees, assurances et cetera.

Improved transparency would support sound practices in public debt management. Making the information available to the public in general would have even stronger beneficial impact on governance, fiscal discipline and adequate risk management.

The better the CF manages to provide transparency, the more lending policies will improve in the long run. In the short run, transparency is needed to restructure debts in an equitable manner.

What the G7 should do

The G7 (Group of leading high-income countries) should provide leadership. It can facilitate equitable burden sharing and discourage non-cooperative attitudes. In particular, G7 members’ national legislation could evolve in a coordinated manner that makes free-riding more difficult and reduces opportunities to obstruct multilateral debt restructuring.

A good example was the Debt Relief Act 2010, which the United Kingdom adopted in 2010. It forced British-based private creditors to take part in the multilateral arrangements to provide debt relief to HIPCs (heavily indebted poor countries).

Another example was how the US and the UK made it illegal to file claims during Iraq’s debt restructuring. They used the UN Security Council Resolution 1483 of 2003 as the blueprint.

It has, moreover, proven useful to insist on the inclusion of collective action clauses (CACs) in loan contracts. Binding commitments of this kind prevent creditors from opting out of restructuring talks.

IFI leadership would be welcome too

Leadership from international financial institutions (IFIs) would be welcome too. The World Bank, for instance, could create a guarantee facility which would boost creditors’ faith in restructured debt.

The IMF has an especially important role to play. It should update its system for Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA) and align it to climate targets as well as the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals in general. Moreover, its programmes should assure creditors of the viability of economic policies. The point is that debt relief must not trigger the next round of excessive borrowing.

A clever proposal was made by Anna Gelpern, Sean Hagan and Adnan Mazarei (2020). They want the G20 to establish a Sovereign Debt Coordination Group, which would consist of representatives from the official and private creditor community. Even without legal authority, the authors argued, this group could convene creditors, collect and disseminate information and facilitate negotiations.

Lessons of the past

In the past, several debt-relief initiatives have been successfully executed. They relied on joint criteria for many parties. Typically, these initiatives were improvised ad hoc, but they set precedents and helped to build institutions such as the Paris Club.

History shows, however, that these successful initiatives were often preceded by half-hearted and unsuccessful ones. Far too often, debt problems were only considered to be issues of liquidity rather than solvency. In our era of multiple crises, we cannot afford to lose time.

Link

Gelpern, A., Hagan, S., and Mazarei, A., 2020: Debt standstills can help vulnerable governments manage the COVID-19 crisis. Washington, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/debt-standstills-can-help-vulnerable-governments-manage-covid

José Siaba Serrate is an economist at the University of Buenos Aires and at the University of the Centre for Macroeconomic Study (UCEMA), a private university in Buenos Aires. He is also a member of the Argentine Council for International Relations (CARI).

josesiaba@hotmail.com