Middle East

Living between hope and helplessness

On his Instagram channel, Alaa Hathleen shares a video of a building from which flickering light falls on the surrounding area. Over the footage, the 25-year-old trained physiotherapist writes: “Settlers burn down the house of Yousef Muhammad Al-Jabarin in Shaab Al-Batm in Masafer Yatta”. Hathleen lives in Masafer Yatta, a collection of Palestinian villages in the West Bank, south of Hebron, that are repeatedly attacked by Israeli settlers.

The area was recently thrust more forcefully into the public eye by the documentary film “No Other Land”. Released in cinemas in 2024, it captures the violence that occurs in Masafer Yatta. “They kill the goats and sheep, cut the cables for the solar panels, destroy our olive groves and set fire to our cars or even homes,” says Hathleen. The activist documents the attacks on Instagram.

In 1981, Israel designated the area as a firing zone for military training. The twelve communities have been resisting forced resettlement ever since. In May 2022, the Supreme Court finally ruled against them. Civil-society organisations such as Amnesty International fear that evictions will now be enforced to make way for Israeli settlements.

The pressure on residents from the Israeli military has increased significantly since that ruling was delivered, as have attacks by extremist settlers. “Soldiers enter villages at night, enforce curfews and other movement restrictions, conduct military training near living areas, confiscate vehicles and demolish homes. They make life unbearable for residents,” says David Cantero Pérez, Médecins Sans Frontières’ head of mission in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, in a press release on Masafer Yatta in 2023.

“As I grew up, I constantly wondered why it is that we have no electricity, no water and no basic rights, whereas the Israeli settlers living in the immediate vicinity do,” says Hathleen. Many young people in the West Bank feel the same way. They feel deprived of their rights, at the mercy of attacks by Israeli settlers and soldiers and abandoned by their government. “Within Palestinian society, there is a strong awareness of personal rights and at the same time frustration over the inability to exercise those rights,” says Nizar Farsakh, lecturer in International Affairs at The George Washington University in Washington DC and former advisor to the Palestinian president. “There is an extreme sense of injustice, and young Palestinians in particular are rebelling against it.”

Loss of legitimacy of the government

For Palestinians in the Occupied Territories, there is no hope of help from their own government. The Palestinian Authority (PA) has administrative and security powers in only parts of the West Bank. In the so-called “C” areas, which make up around 60 % of the West Bank, Israel has complete control. Palestinian security forces are not allowed to operate there, not even to protect their own population. In addition, the PA is contractually obliged to cooperate with Israeli security forces. This is perceived by many Palestinians as collaboration with the occupying regime and undermines their trust in the PA.

According to a survey conducted by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PCPSR) in March this year, 84 % of Palestinians want to see PA President Mahmoud Abbas resign. Only eight percent of Palestinians in the West Bank are satisfied with his work. Sven Kühn von Burgsdorff, the EU’s ambassador to the Palestinian Territories between 2020 and 2023, explains: “The government of Abbas and Fatah has lost all authority and legitimacy among the vast majority of Palestinians. They are seen as enablers of the occupation.”

Anger over the occupation and the lack of representation by their own government prompt many Palestinians to take their fate into their own hands. “Palestinians know that they can expect no help from their own government and security forces,” says Kühn von Burgsdorff. The ex-diplomat sees this as the reason why young Palestinians, in particular, have become increasingly willing to resort to violence in recent years. “Older generations are less open to violence than younger ones because they carry the trauma of the bloodshed during the second intifada and thus want to avoid the use of violence,” Kühn von Burgsdorff explains. During the first intifada (1987 to 1993) and the more violent second one (2000 to 2005), Palestinians rebelled against the Israeli occupation.

Growing influence of extremist groups

The growing willingness of young Palestinians to use violence benefits militias and extremist groups such as Hamas. According to a study conducted in May by the consultancy firm Arab World for Research and Development (AWRAD), 34 % of 18- to 24-year-old Palestinians in the West Bank would currently vote for Hamas. That would make it the strongest force in the West Bank. Only 13 % of respondents said they would vote for the ruling Fatah party.

There are also militias on the scene. For example: the “Lions’ Den” in Nablus in the central West Bank and the “Jenin Brigades” further north. Young Palestinians look to such groups for identity and a chance to express their frustration. They hope to find a community that fights for justice and self-determination. “Militias primarily developed in the Palestinian refugee camps. Palestinians living in the refugee camps have nothing more to lose; they have already lost everything,” says Farsakh.

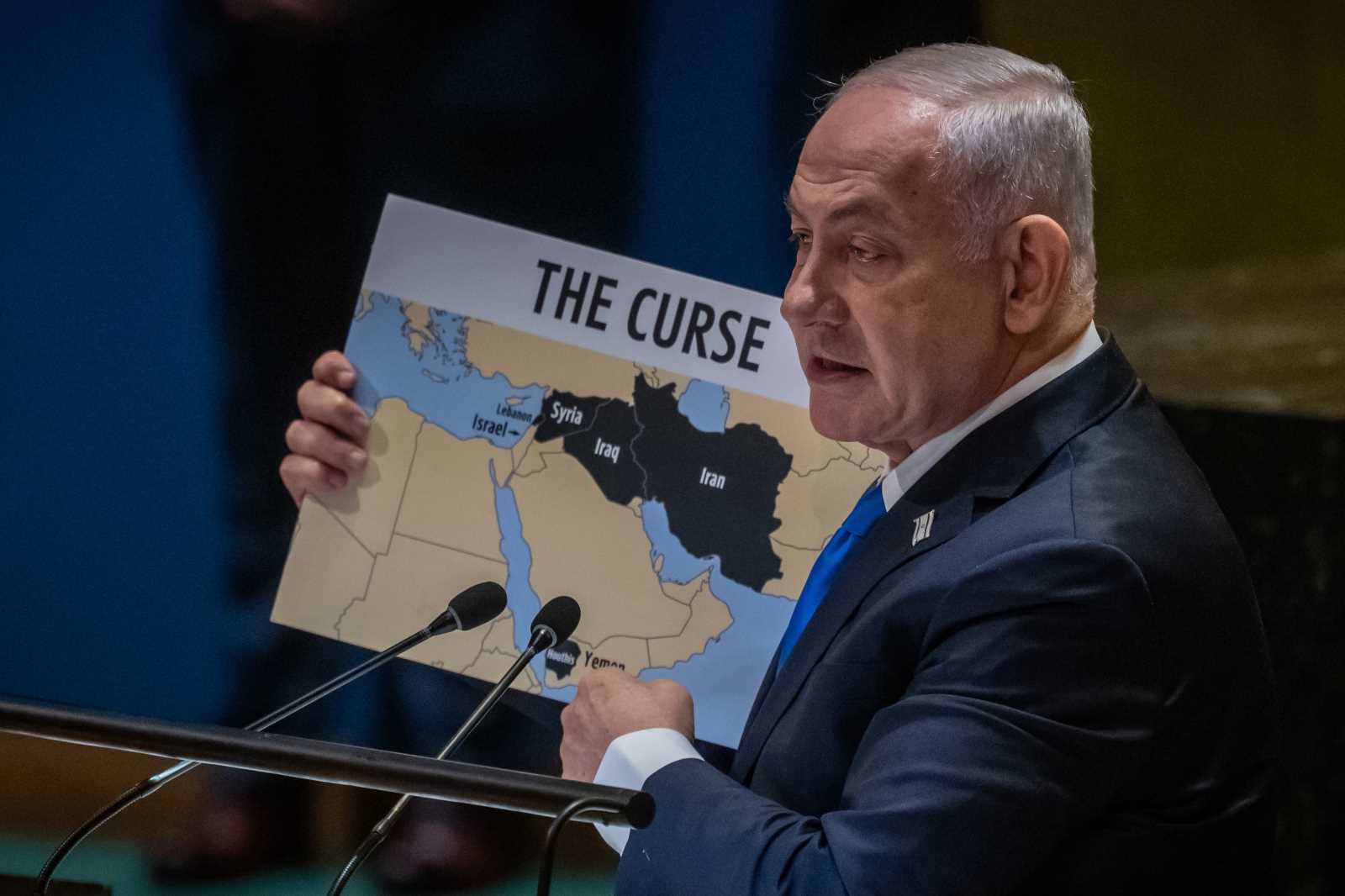

Due to the increasing violence on both sides, radical religious forces are gaining more and more influence. Religious rhetoric is instrumentalised by extremist Palestinian organisations as well as by the Israeli government and the settler movement in order to achieve political and ideological goals and mobilise supporters. Religion is frequently used to legitimise extreme beliefs and increasingly side-lines secular movements.

To break the spiral of violence, former EU envoy Kühn von Burgsdorff believes that Israel needs to change its position. “The problem is that the system is too profoundly unjust. The situation will only change when the structural violence of the occupation ends,” he says. In his view, the US and Europe should press Israel to give up the occupation.

There is no end to the violence in sight. Since Hamas’ terrorist attack on Israel on 7 October 2023 and the subsequent outbreak of war, the situation in the West Bank has continued to deteriorate. The recent approval of new settlements by the Israeli government has further fuelled the tense situation.

Kim Berg is an editor at the communications agency Fazit and specialises in political communication.

kim.berg@fazit.de