Education

Hope for Cameroon’s children – just not enough

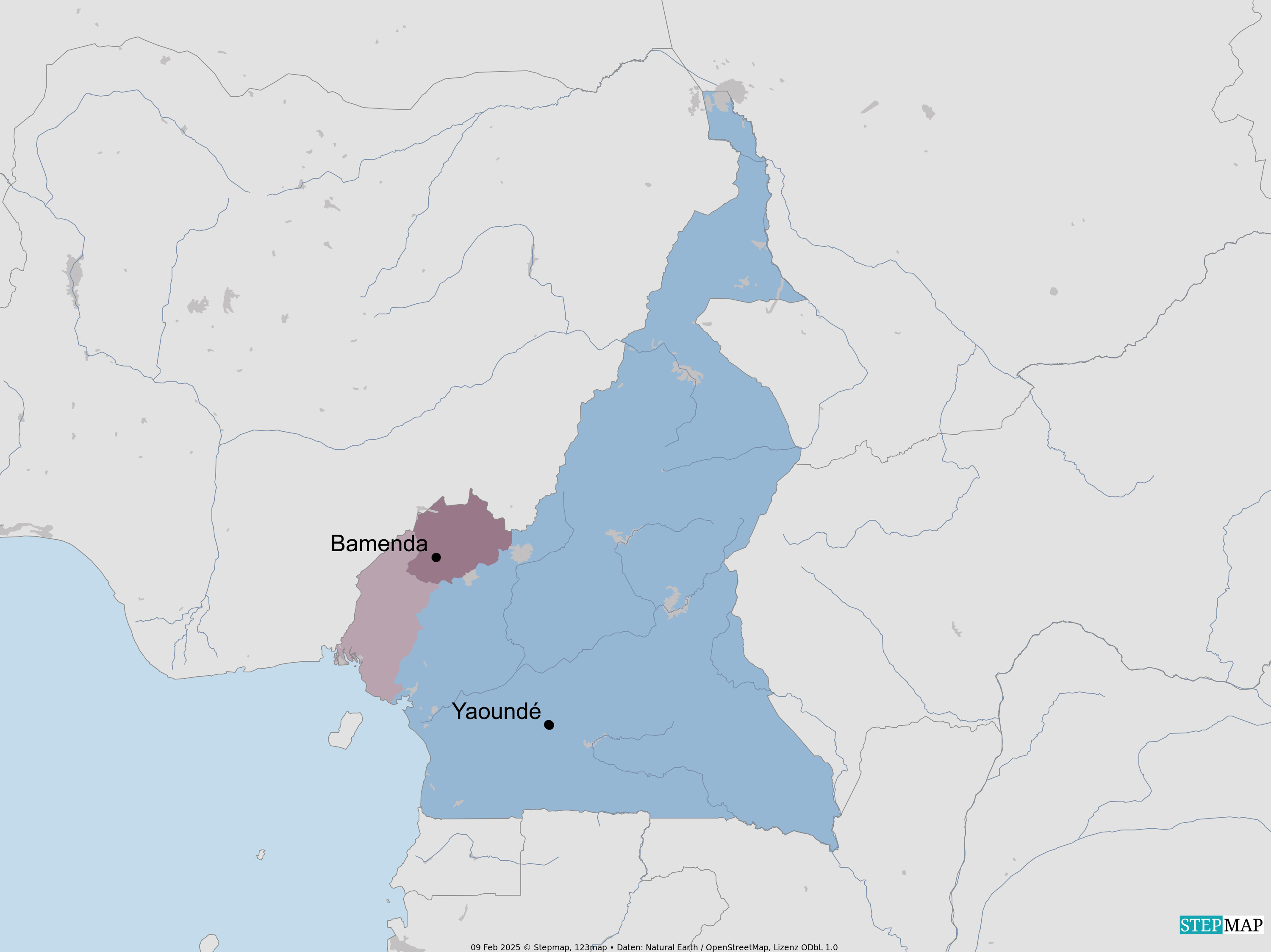

An ongoing armed separatist conflict in Cameroon’s Anglophone North West and South West regions has shown no sign of abating for eight years now. There is a glimmer of hope for the vulnerable children who have been out of school for years, however.

Last July, the European Union announced that it would provide more than 1.7 billion CFA francs (about $ 2.8 million) to preserve the educational and learning prospects of a generation of children whose future has been jeopardised by the bloody conflict.

The aid will cover two school years and is intended to provide educational materials and safe, child-friendly learning spaces with water and sanitary facilities.

In addition, the funds are used to support the issuing of birth certificates for school-age children who do not yet have one, ensuring their right to citizenship status and access to further education. Many have either never received this important document or it was destroyed during the fighting.

According to the representative of the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in Cameroon, Nadine Perrault, these additional funds are urgently needed for the children. She points out that together with women, children are the most affected by the Anglophone crisis, as is the case in almost all conflicts. Perrault explains that the funds will address multiple humanitarian needs through a multi-sectoral intervention in education, WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) and protection for children affected by the conflict in the two regions.

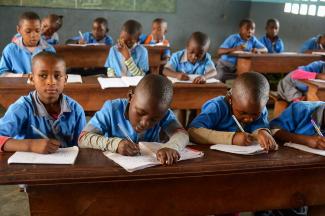

“Education is a lifeline for children. We are working to provide uninterrupted education for every child. We are further helping children develop skills to cope with experienced trauma,” says Perrault, adding that the additional funding from the EU’s humanitarian aid will help UNICEF to rapidly scale up its operations and improve access to learning opportunities for children both in and out of school.

The localisation agenda in humanitarian aid aims to engage various civil-society organisations on the ground as implementing partners for a sustainable response. Therefore, UNICEF will engage organisations like Green Partners Association (GPA), Foundation for Inclusive Education and Development (FIED), Queen Fongang Foundation (QFF), Community Health and Social Development for Cameroon (COHESODEC), Strategic Humanitarian Services (SHUMAS) and others.

Efforts so far remain insufficient

However, according to Perrault, only around 54,000 of the estimated 488,000 children who do not attend school are likely to benefit directly from the measures. “The project only targets children in the North West and South West regions, as envisaged by the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT). The HCT is the decision-making body made up of the operationally relevant humanitarian organisations and focuses humanitarian aid primarily on the epicentres of the crisis, where the need is greatest,” she says. Those who have fled to other regions are being sidelined. UNICEF is therefore calling on all donors and other strategic partners to step up their support to ensure that all children affected can be reached.

Agendia N. Atemnkeng, a Yaoundé-based educator, applauds the initiative, saying that if well utilised, it will go a long way in bridging the already wide education gap that exists between children in the conflict regions and their peers in other parts of the country.

However, as most of the support will be material, Atemnkeng questions the sustainable impact of the donation. He suggests that a large part of the support should at least go towards providing reusable materials so that they can serve the children for at least three school years.

“Supporting education during a crisis goes beyond the provision of materials. Education stakeholders in crisis areas, especially teachers, must receive specialised training on how to teach children in such conditions,” Atemnkeng says. Training should include trauma management, adapting the curriculum to focus on the most important aspects and emphasising vocational training after primary school years, among other things.

The Cameroonian government has pursued one strategy after another with little success. For example, a redistribution centre with special security measures was set up in the administrative unit of Ngoketunjia near the North Western regional capital of Bamenda. The idea was to move non-functioning schools and their students and teachers from outlying areas where the security situation had deteriorated to the centre, which was heavily guarded by armed troops. However, as there were only limited accommodation facilities available at the centre, the students had to return home after classes, exposing them to even greater danger. The result: empty classrooms.

Handerson Quetong Kongeh, Senior Divisional Officer of Ngoketunjia, told the state television station CRTV late last year that concerted efforts are needed to return to normalcy. He reported that the strategy of regrouping the centres will be abandoned and that several schools will open at their actual locations.

In 2023, a submission to the UN Human Rights Council examined the human-rights situation in Cameroon. It strongly recommended that the government of President Paul Biya should “take effective measures to guarantee the safety of students and educational staff throughout the territory.” Biya has ruled the country since 1982.

The government accepted the recommendation but has largely paid lip service to it, claiming that the situation is under control. It must urgently take the necessary steps to resolve the conflict and end the violence. However, the government maintains that it will not negotiate with the separatists, whom it describes as “terrorists”, and is relying on the military option, which has not proved successful for eight years.

Amindeh Blaise Atabong is a Cameroon-based freelance journalist who has reported on various topics from across Africa. aamindehblaise@yahoo.com