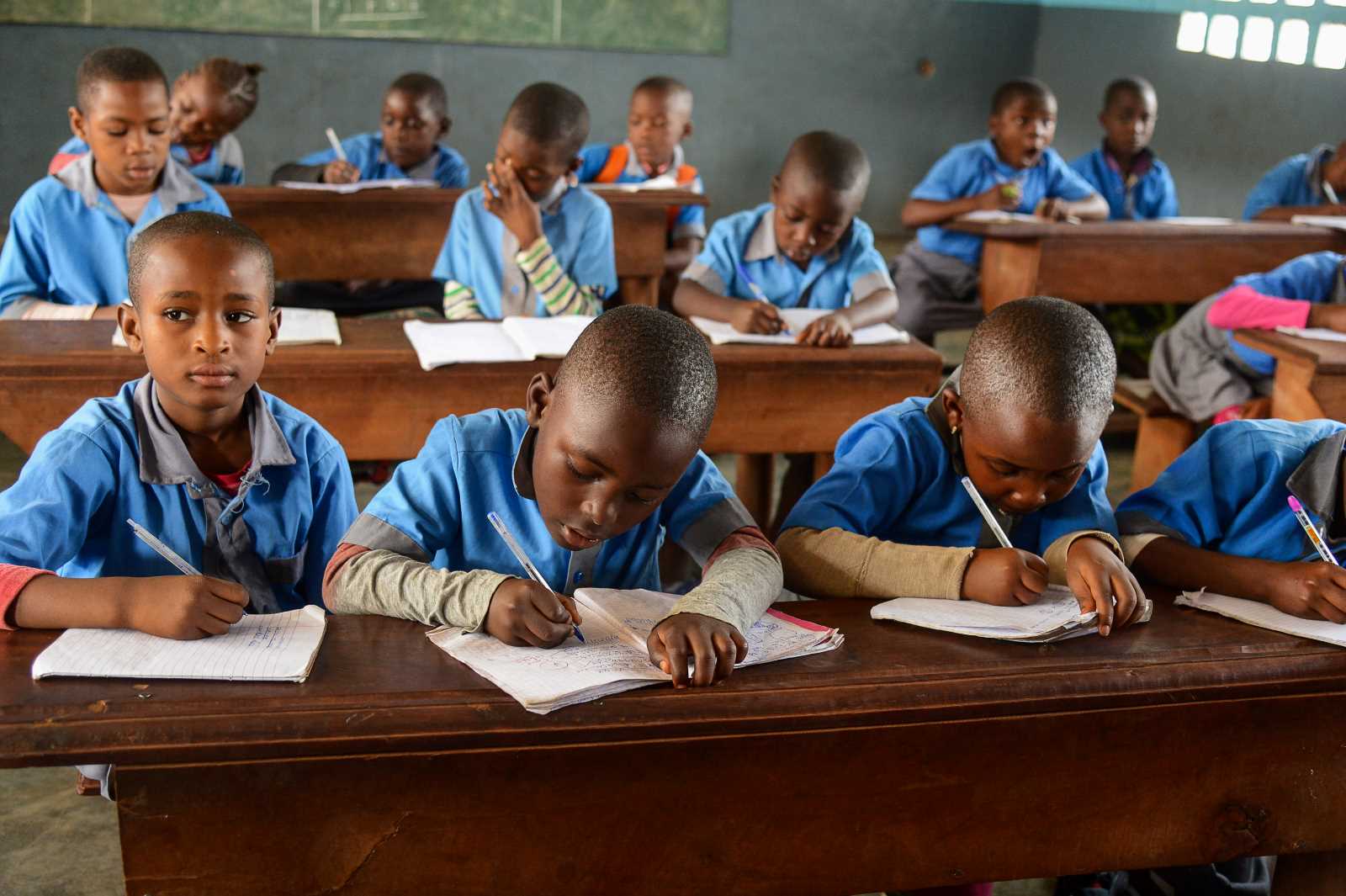

Children in conflict

Almost half a million Cameroonian children are out of school

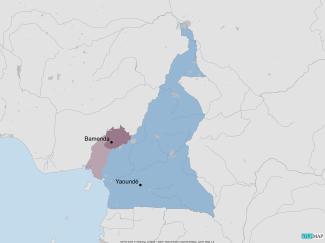

Around 25 % of children between the ages of three and 17 are still unable to go to school in the conflict-ridden regions of North West and South West Cameroon, according to the Cameroon Education Cluster. More than 488,000 children are thus deprived of their right to education. About 2000 schools, corresponding to 41 % of schools in the two troubled regions, are still not functioning.

The conflict has its roots in colonial power relations between Britain and France (and to a lesser extent Germany). It was also triggered by Anglophone dissatisfaction with Francophone control over education. Thus, since the fighting has flared up eight years ago, educational institutions have become primary targets.

School furniture and materials such as desks, benches, chairs and chalkboards were destroyed. Students and teachers who defy the school boycotts imposed by the separatists have been victims of brutal murders, rapes, abductions, torture and other cruel treatment. Numerous schools were set on fire. Human-rights groups accuse non-state armed groups as well as government forces of alternately committing such atrocities.

As the fighting between the government troops and the armed separatists intensified, most of the schools were closed and have since been used as military bases by the warring parties, while internally displaced persons and families have also found refuge in them.

The schools that have managed to stay open are forced to constantly cancel classes. Children miss at least 51 days per school year due to insecurity, imposed lockdowns and curfews.

Cameroon still ranks second on the latest Norwegian Refugee Council’s list of the ten most neglected crises in the world. According to the NRC, the funding gap for humanitarian aid is large, resulting in millions of people not having enough to eat, families repeatedly fleeing in search of safety and resources and children not having access to education.

Suffering from the consequences of the protracted conflict, parents are unable to support their children’s education by providing money for lessons, teaching materials, food, or healthcare. They have no choice but to put their livelihood before their children’s education.

It is therefore important to note that funding and support from the international community, such as that provided by the EU last year (see main text), is urgently needed and means new hope for many out-of-school children and their parents.

Amindeh Blaise Atabong is a Cameroon-based freelance journalist who has reported on various topics from across Africa. aamindehblaise@yahoo.com