Cheaponomics

Why cheap is expensive

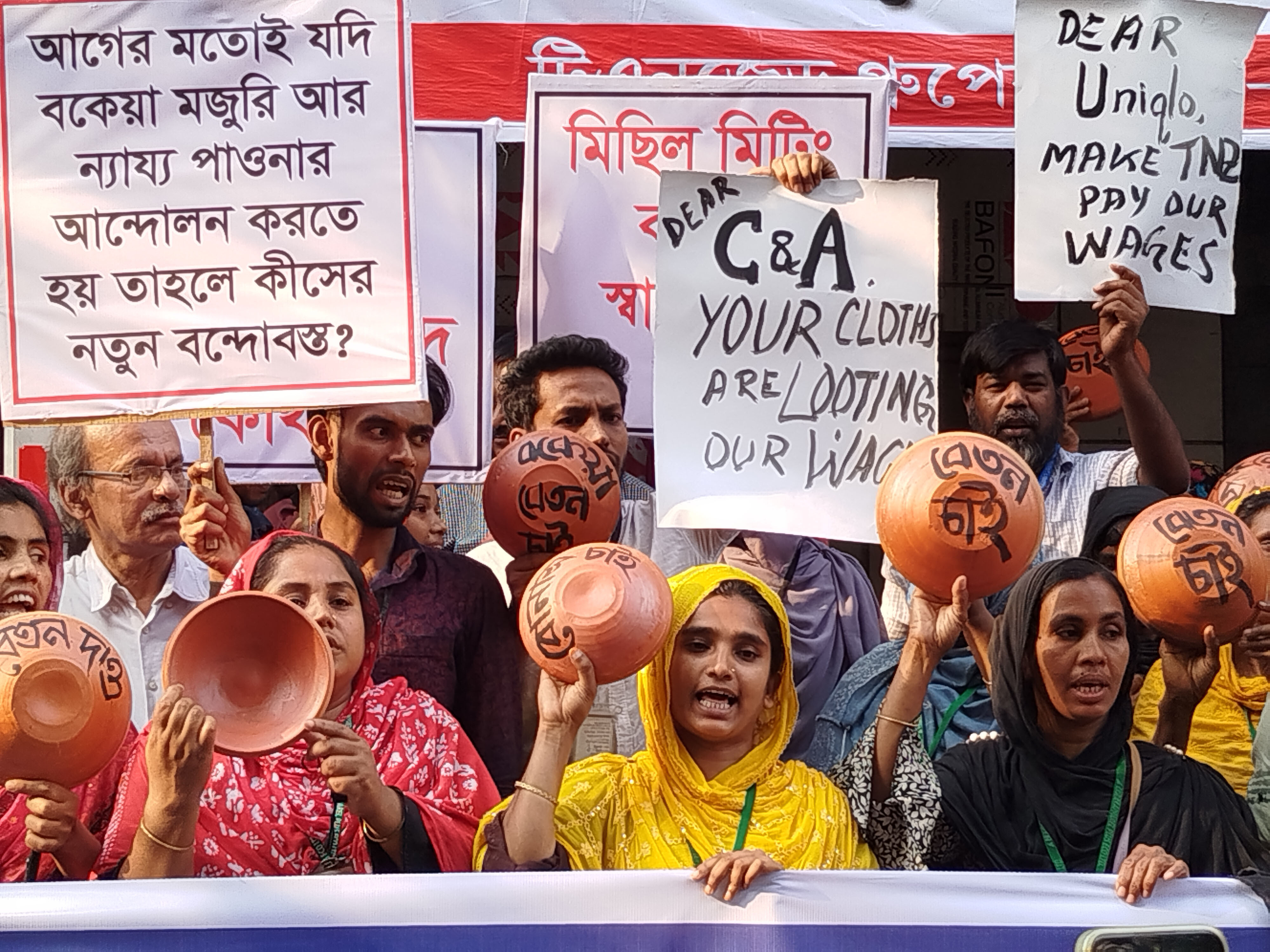

The discount supermarkets and department stores of advanced nations are full of cheap food, clothing, electronic goods, toys and other goods. Buyers purchase them lawfully, argues Carolan, but they do not pay the true price. Cheap goods, he points out, are produced at the expense of people who live in poor countries, earn only very low wages and risk their health working in inappropriately managed factories or mines. In countries with fragile statehood such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, moreover, terrorist militias are involved in the fight over natural resources such as Coltan, which is used in mobile-phone production. Carolan adds that the production of cheap consumer goods tends to be environmentally harmful.

According to Carolan, the marketing of cheap goods does not even serve rich nations. One reason is that these goods make the low-wage sector grow since people will accept lower wages as prices drop. In Carolan’s eyes, society as a whole is paying the price. Low-income groups, after all, are supported with governmental welfare payments or housing subsidies which are funded with tax-payer money.

The scholar states that consumers in rich nations know about the true costs, but they do not really ponder the issue and certainly don’t change their behavior accordingly. Big corporations are the ones who profit most, the professor at Colorado State University argues. They neither pay workers appropriately, nor do they protect the environment. Such cost avoidance is destructive, Carolan states, and it is symptomatic of a global economic system that channels profits to small sections of society while making broad majorities bear the costs. Carolan calls this “cheaponomics”.

His book solidly assesses the hidden costs for a number of goods and industries. It also indicates solutions. First of all, Carolan wants us to move on from the conventional wisdom. In his eyes, for example, economic activity is not necessarily linked to permanent economic growth. He also insists that criticism of market failure is not the same as demanding more government intervention.

Carolan’s book includes several important messages that people should take to heart:

- The prices of cheap goods and services are illusionary because the real costs are born by other people today and in the future.

- Even consumers do not really benefit from cheap goods because these goods do not last long and need to be replaced soon.

- Factoring in the true costs raises prices in the short run, but does not increase long-term expenditure because sustainability matters too.

- Higher prices do not necessarily imply that people can afford less. The real challenge is to balance consumption, work and leisure intelligently.

- Cheaponomics results from a distorted idea of markets and neglect for relevant impacts of business activity.

The author calls for public debate of these issues and proposes tangible action. In his view, social and political problems need to be tackled, whilst markets as such are not the core problem. The sociologist demands more transparency and democracy, for instance in regard to the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund. He is also in favour of passing and enforcing anti-trust legislation to stabilise prices and put better checks on private-sector companies. He would appreciate higher taxes on the wealthy as well as insolvency rules to protect private and governmental debtors from ruinous interest rates.

Sabine Balk

Reference:

Carolan, M., 2015: Cheaponomics – The high cost of low prices. New York/Abingdon: Routledge