International relations

Why India and China are realigning their relations

The Durga Puja celebrations in India are an annual festival to worship the Hindu mother goddess Durga and celebrate the triumph of good over evil. The festivities in the state of West Bengal are the biggest of their kind and a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. During the celebrations in September this year, some clay idols of Durga depicted her slaying a demon who bore a striking resemblance to US President Donald Trump. By incorporating such political symbolism into a socio-religious festival, locals were expressing their anger over the most recent trade tariffs of the Trump administration.

Trump’s trade policy has had a severe economic impact. His administration has imposed tariffs as high as 50 % on Indian exports such as apparel, jewellery, chemicals and footwear, which make up more than half of the country’s $ 87 billion in annual exports to the US. Preliminary estimates suggest that tariffs may cut India’s US-bound exports by more than half in the medium term, which would put up to 0.9 % of India’s GDP at risk and threaten millions of jobs, particularly in labour-intensive sectors like textiles, gems and fisheries.

China has felt the impact of Trump’s tariffs, too, which peaked as high as 145 % on some Chinese exports. China responded with counter-tariffs and export controls on rare earths. However, a meeting between Trump and China’s President Xi Jinping in South Korea at the end of October sent signals of de-escalation.

“These disruptive tariffs threaten India’s export-oriented sectors, have strained ties with Washington and prompted a decoupling in US-China trade, forcing India and China to pursue new alliances in a shifting global order,” said Sitaram Sharma, president of the Tagore Institute of Peace Studies (Tips). He pointed out that the US tariffs against India are widely seen as retaliation for New Delhi’s imports of Russian oil. The US and other nations, including the UK and members of the EU, have imposed sanctions on Russia because of Putin’s ongoing attack on Ukraine.

Sharma spoke at an academic conference in Kolkata in mid-September where several scholars from India and China discussed how global developments are shaping the two countries’ relationship. The event, “Shifting Geopolitics: A New Framework for India-China Relations”, was organised by Tips and the Consulate of the People’s Republic of China in Kolkata.

Looking for other options

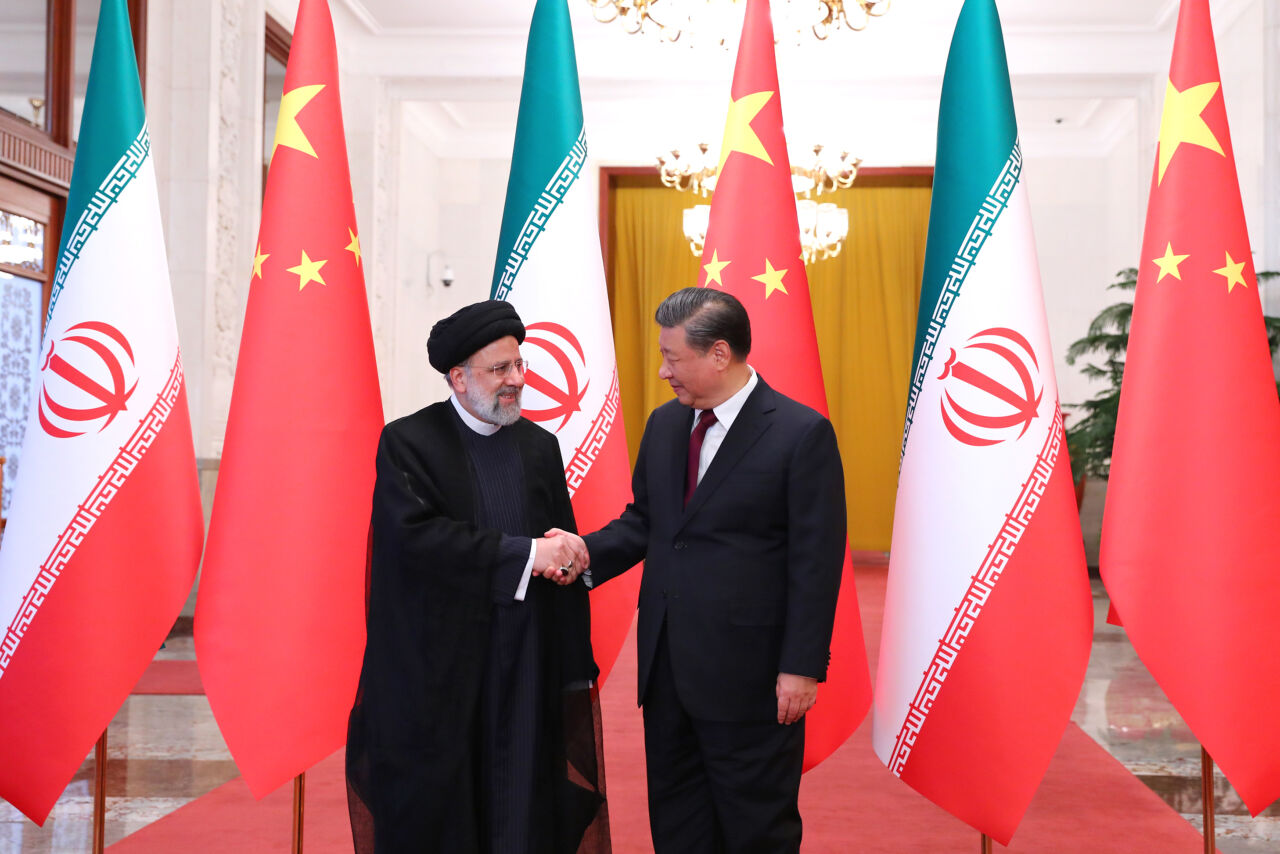

The scholars discussed how the latest US tariffs have encouraged India to pursue closer ties with China, Russia and other countries. India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited China after a seven-year hiatus and met with China’s President Xi Jinping at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in Tianjin in August and September. Russian President Vladimir Putin attended the summit, too. These developments indicate a strategic reset of the ties between India, China and Russia.

Both India and China are seeking new markets in Latin America and the Middle East to buffer against US trade shocks. China is also seeking to diversify towards the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and African countries, in addition to increasing domestic consumption.

“The two two largest developing economies are at a critical stage of national development and rejuvenation”, said Qin Yong, China’s acting consul general in Kolkata. He was referring to both China and India pursuing their respective development goals as spelt out in China’s Second Centenary Goal (2049) and India’s Viksit Bharat (Developed India) 2047. Qin emphasised that trade between the two countries reached $ 88 billion in the first seven months of this year, a year-on-year increase of 10.5 %. “Only by strengthening mutually beneficial cooperation can China and India achieve a win-win outcome and hand-in-hand development,” he said.

Yet this possibility is fraught with problems. At the conference in Kolkata, several scholars underscored the legacy of mistrust between Beijing and New Delhi while emphasising the need to convert the environment of conflict to one of cooperation. Ishani Naskar of Jadavpur University in Kolkata stressed that the shared geography and colonial legacy of India and China are shaping current challenges. “We cannot run away from each other,” she said. In her opinion, the two countries should focus on working through hardships and strengthening trade.

Difficult relationship

Relations between India and China have suffered severely in recent years. There have been repeated skirmishes on the shared border in the Himalayas, for example. More than 20 soldiers from both countries lost their lives during a border conflict in Galwan Valley in 2020. “Bilateral relations fell to the bottom”, recalled Zhang Jiadong from Fudan University, China. “India cancelled multiple Chinese enterprise investments and restricted technology exports, while China strengthened border infrastructure construction,” he said.

Unsurprisingly, the Modi government promoted a “self-reliance” policy, while China deepened its ties with ASEAN. According to Zhang, the events amplified the supply chain disruptions during the global pandemic. Fortunately, the conflict did not evolve into full confrontation, Zhang said, adding that both countries demonstrated great restraint.

The two nations succeeded in easing tensions. In October 2024, a border patrol agreement accelerated the de-escalation process and was followed by a bilateral meeting in Russia and Modi’s attendance at the SCO summit. High-level meetings restarted. Zhang analysed that even though recovery has not been smooth, the leadership of both countries is clearly committed to stabilising relations. “In a changing world, China and India cannot afford the cost of prolonged confrontation,” he said. For Zhang, the 2024 border agreement marks “a breakthrough”.

Huang Yunsong from Sichuan University, China, emphasised the importance of institutionalised trust-building, such as through the real-time “trust hotline” established between the armies of both countries in 2021. He described it as a “24/7 mechanism for real-time coordination, supplemented by joint exercises in non-sensitive areas to foster military-to-military ties.”

The need for trust was echoed by Tridib Chakraborti from Adamas University, India, who emphasised institutional mechanisms for conflict management: “The strategy ahead must be grounded in realism and oriented towards regional and global stability.”

Suranjan Das, Vice Chancellor of Adamas University, India, referred to the enormous prospects for cooperation between China and Eastern India in particular.

Neither allies nor enemies

Yet these opportunities do not mean that India and China will become allies. Zhang Jiadong held that becoming allies would not conform to China and India’s respective strategic autonomy. However, he stressed that the two countries “should not become enemies, as that would amplify global risks.” He maintained that India’s trade deficit with China of $ 99 billion represented “interdependence”. “If unmanaged, the deficit could fuel protectionism; if harnessed, it could propel combined GDP growth beyond seven percent annually, lifting millions out of poverty,” Zhang said.

As India is recalibrating its relationships with regional blocs and countries, it is likely to deepen ties with Russia, too. The two countries have a tradition of geopolitical cooperation, and Russia has supported India in difficult situations. Economic ties include the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), which connects Mumbai to St Petersburg via Iran, Azerbaijan and the Caspian Sea. The corridor is enhancing regional economic integration between India, Russia, Iran and Central Asia.

What’s next?

On the sidelines of the conference in Kolkata, scholars discussed possible consequences of these geopolitical and economic shifts. These include:

- A reinforced Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, which would serve as a more inclusive and cohesive platform for collective diplomatic strategy in Eurasia and be more strongly influenced by the changing India-China-Russia dynamics.

- An expansion of the BRICS+ group, which currently comprises Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa and other countries, including deepened economic cooperation between member states.

- A reinvention of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, (SAARC) comprised of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka or a new regional grouping, which would impact South Asia’s geopolitical alignment and connectivity.

- Coordinated efforts to create alternatives to Western-dominated international institutions through global multipolar alliances as countries aim to gain more economic sovereignty and resilience by engaging in diversified multilateral partnerships.

Countries around the world are seeking greater control over critical resources and strategic sectors to protect themselves against external political shifts. India’s future relationships with other countries and regional blocs will be shaped by its determination to preserve its strategic autonomy. While India’s national security concerns are prompted by both China and the USA befriending arch-rival Pakistan, it is in India’s economic interest to engage in nuanced, pragmatic cooperation beyond ideological or historical alignments.

Aditi Roy Ghatak is a freelance journalist based in Kolkata and Delhi and Dean of the Tagore Institute of Peace Studies.

aroyghatak1956@gmail.com