International affairs

Why BRICS+ may prove weaker than expected

In a study published in 2001, Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neill coined the term BRIC, referring to Brazil, Russia, India and China. The acronym was meant to guide investors towards emerging economies with higher growth rates than high income countries. Moreover, these nations were large in terms of GDP (gross domestic product), population and territory. It seems ironic today that the term was coined by a Wall Street banker and initially lacked any political ambitions.

The acronym gained attention. Leaders from the BRIC countries began to meet and talk. At first, they did so on the sidelines of international events, but from 2009 on, they launched periodical BRIC meetings. BRIC thus became a political reality. The joint objective was to get more say in international institutions – in particular the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund – in accordance with their growing economic power.

South Africa joined in 2010, thanks to a Chinese initiative. By including Africa’s largest and most developed economy, the informal BRICS could now claim to represent this continent. To the original four members, moreover, South Africa became a gateway to the continent. A side effect was the weakening of IBSA, the more homogenous grouping of India, Brazil and South Africa. All three countries have fully operational democratic constitutions.

BRICS scepticism and achievements

The west was always sceptical of the BRICS. Observers pointed to the diverging interests of five rather different countries which neither had much in common historically, nor much ongoing political and economic interaction. Members, moreover, could hardly be considered to be regional leaders with a mandate to speak for Asia, South America or Africa.

Nonetheless, BRICS initiatives expanded to various more or less institutionalised areas of international affairs. They range from think-tanks and academics to civil society, businesses, healthcare and tax authorities. Healthcare, in particular, always seemed a promising issue-area for BRICS cooperation. The members are highly impacted by HIV/AIDS and drug-resistant tuberculosis, but they also have impressive vaccine and drug manufacturing capacities.

However, international finance was and is the main area in which the BRICS have a common agenda. The 2008 financial crisis started in the USA and quickly spread to western Europe. Emerging markets weathered it relatively well by contrast. Accordingly, demands for reforms of international financial institutions seemed only logical. When the long-established powers refused to give the BRICS more say as fast and to the extent demanded, they set up institutions of their own. The Shanghai-based New Development Bank (NDB) serves as a counterpart to the World Bank and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement as one to the IMF.

Intra-BRICS tensions

Western BRICS scepticism was not entirely wrong, however. When a recession started in Brazil in 2014, some questioned whether it really deserved a place in BRICS. More recently, South Africa’s economy has been sliding into stagnation too. Long-standing territorial disputes between India and China add to difficulties.

However, China’s dominant role in the BRICS and its disproportionate geostrategic power also amount to a menace to the cohesion of the group. Intra-group tensions, however, did not lead to its collapse.

Even before its attack on Ukraine in 2022, Russia strove to turn the BRICS into an anti-US and even anti-western group. China has similarly taken an antagonistic stance towards the US, in both geostrategic and business terms. Western observers suspect that the BRICS may be an instrument in the budding new cold war.

The BRICS are still active, even though Russia’s top leader Vladimir Putin missed last year’s summit in South Africa. He did not travel there because the International Criminal Court has issued an arrest warrant. South Africa, as a signatory of the ICC statute, would have had to detain and extradite him. Putin shied away from making South Africa choose between loyalty to the BRICS and loyalty to the ICC.

Becoming BRICS+

At the summit last year, the BRICS decided to admit new members. With Russian support, China had pressed for such an expansion. India and Brazil initially opposed the admission, while accepting that additional countries could be admitted as observers or with some other kind of non-member status.

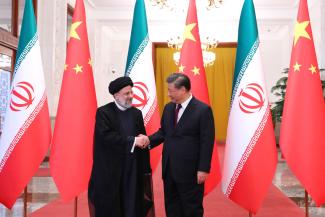

By 2023, more than 40 countries had expressed interest in joining BRICS, and 23 formally applied to join. In Johannesburg, China (and Russia) prevailed. Six new members were admitted into BRICS: Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Indonesia had also been invited to join BRICS but declined. A few months after the summit, Javier Milei, Argentina’s new president, decided against joining – to the disappointment of Brazil’s government, which had wanted its neighbour and Mercosur partner to become a BRICS member. Saudi Arabia has not formally joined yet but is still expected to do so soon.

The other four countries – Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran and the UEA – are now BRICS+ members. They are all in the Middle East and its surrounding region. Two are major oil-producing countries, and Saudi Arabia will probably become yet another fossil-fuel rich member.

The choice of countries reflects China’s interest in countering US influence in the Middle East. India and South Africa, however, share China’s interest in access to fossil fuels. A further de-dollarisation of energy markets is to be expected and would serve the interests all BRICS+ members.

Prospects for an enlarged BRICS

From the outset, the four-member BRIC faced difficulties in reconciling diverging interests. Apart from significant achievements in regard to international finance, the group has rather little to show. In particular, international security is an issue-area where the BRICS each go their own way.

Many may think that the inclusion of new members will strengthen the group. After all, the combined GDP, territory, population, natural assets et cetera became significantly greater. In reality, however, the strength of the BRICS does not result primarily from the joint significance of their economies. What matters is the capacity for collective action. In this regard, long-standing tensions between some of the new members are important. For example, the use of Nile water as a contentious topic for Ethiopia and Egypt may matter too.

It will probably matter more that Iran and Saudi Arabia compete for hegemony in the Middle East. The UAE is not only the Saudis’ close ally, but also has territorial disputes with Iran regarding islands in the Persian Gulf. For decades, both Gulf monarchies have been maintaining close ties to the USA. On the other hand, China did succeed in brokering rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran, and that may have impacts on the wider region.

Scholars have long pointed out that collective action is much easier and less costly in smaller than larger groups, because the influence of each individual member on joint decisions is greater and because monitoring is easier and cheaper in the former. Even with only five members, collective action by the BRICS mostly proved difficult. With four – and maybe five – additional members, these difficulties may prove unsurmountable. The only original member that is expected to enjoy increased influence is China.

It is also striking that, after the withdrawal of Argentina, no new member is a democracy. None of them performs well in regard to human rights, gender rights or minority rights. These issues never figured prominently on the BRICS agenda and are now even less likely to do so.

What now?

Of the new BRICS+ members, Iran is likely to benefit the most, as it becomes less isolated and enjoys greater opportunities for trade and investment. Non-dollarised trade will help it too. More generally speaking, the BRICS+ is bound to become another channel for Chinese influence. However, it may turn out to be irrelevant if joint action becomes impracticable.

The main objective of the expanded BRICS is still not clear. To counter US hegemony may be the ultimate plan of China and Russia. But will other members follow suit? Though India, South Africa and Brazil also have a history of keeping their distance to Washington, they have been more open to cooperation with western governments in the past. Apart from Iran, moreover, the new members have all belonged to the pro-western camp for a long time.

Accordingly, the BRICS+ may not have much impact in international affairs. As for intra-BRICS+ relations, expectations do not seem much brighter. If they have failed to achieve concrete results before the expansion, they are even less likely to do so now. Even China seems to be hedging its bets. Rather than boosting the NDB, it established the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in Beijing. It is yet another multilateral development bank, but it involves western member countries.

The prospect of the BRICS+ taking a united stance on important global issues is not on the horizon. The group’s explicit aspiration of becoming “the voice of the global south” looks exaggerated, given that it only includes one single least-developed country, Ethiopia.

André de Mello e Souza is an economist at Ipea (Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada), a federal think tank in Brazil.

Twitter: @A_MelloeSouza