International relations

A brief history of the BRICS

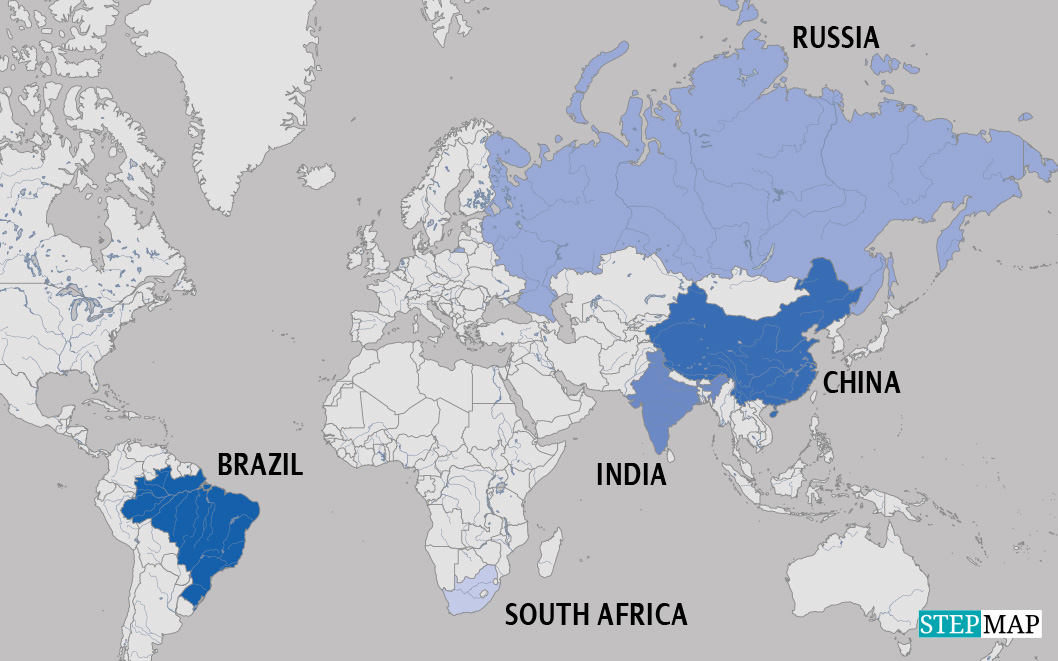

Two decades ago, Jim O’Neill, a manager at Goldman Sachs, the New-York based investment bank, coined the acronym BRICs. It stood for Brazil, Russia, India and China. In his eyes, these four emerging economies stood out due to high growth rates and large populations. The political systems, however, were very different, ranging from representative democracy to full-blown dictatorship. The economic models were very different too, and so were history, culture and geography. Russia spans half of the Arctic Circle, while India and Brazil are mostly tropical countries.

Nonetheless, the new term became popular, including in the countries concerned. In 2006, the four foreign ministers of the BRICs met on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in New York. In 2009, the inaugural BRICs’ summit took place in Yekatrinburg, Russia, and annual summits have taken place ever since. The latest one was a digitised event, hosted by China’s president Xi Jinping in June.

Capitalising the “s”

When South Africa joined in 2010, the “s” in BRICS was capitalised. By that time, the global context had changed considerably. In 2008, Lehman Brothers, another New York investment bank, had collapsed, triggering a financial crisis which spread around the globe. The G7 (Group of seven major high-income economies) had been hit especially hard. That emerging economies were faring better bolstered their international standing. From late 2008 on, the top leaders of the 20 largest economies (Group of 20 – G20) had begun staging annual summits. They involved the G7, what was yet to become the five-member BRICS as well as several other nations.

The BRICS account for roughly one quarter of global GDP in dollar terms and one third in purchasing power parities. About 40 % of the world population lives in a BRICS country. The latest annual summit was a digitised event, hosted by China’s president Xi Jinping in June.

Group’s appeal is not based on common agenda

Several other developing countries and emerging markets have stated their interest in joining the group. They include Indonesia, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Egypt, Nigeria, Senegal and Argentina. Given that the BRICS do not have a clear agenda, its appeal seems awkward. What it shows, however, is that many governments are uncomfortable with the US-led G7 dominating the global arena. Quite obviously, they see the BRICS as a potential counterweight.

So far, however, the BIRCS have not been able to play such a role. They lack a coherent agenda. There has been a lot of talk regarding various economic issues, of course, but apart from one exception, big announcements did not result in tangible projects or meaningful multilateral initiatives. So far, the BRICS have only one new joint institution: the Shanghai-based New Development Bank (NDB) (see box). Other announcements concerned things like an innovation partnership, a contingent foreign-exchange arrangement or a BRICS credit rating agency. None of them materialised.

Awkward allies

Part of the problem is that the BRICS do not agree on much apart from not accepting a unipolar world and rejecting US hegemony. As the macroeconomic situations of the five countries and their strategic interest diverge considerably, they struggle to find common ground. In particular, India and China are not natural allies, but rather fierce competitors. The security situation along the Sino-Indian border in the Himalayas is tense, and soldiers are indeed killed occasionally.

India, moreover, is largely bypassed by China’s Belt and Road Initiative, a massive international infrastructure-investment programme which has financed projects in Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. In view of mounting sovereign-debt problems, however, it is not clear that they are really beneficiaries. In any case, the Belt and Road Initiative shows that Beijing sees New Delhi as a rival and that it is dealing with international debt issues on its own and not in concert with BRICS partners.

Trade between the five countries has actually been in decline, and the Covid-19 pandemic is not the only reason. Trade frictions between India and China are becoming increasingly evident.

The G7 are eager to exploit tensions within the BRICS. India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa were both invited to the recent G7 summit in Bavaria. They attended a side-event, and that must have made alarms ring in Beijing. China has indicated an interest in expanding the BRICS, but other members seem to prefer keeping it small. All five are doing what suits their national interests.

Disappointment in the G7

International Disappoint in the G7 has many reasons (see interviews with Anna-Katharina Hornidge and Vladimir Antwi-Danso on www.dandc.eu). For the purpose of this essay, I will restrict myself to pointing out that the global South has heard many long lectures on prudent macroeconomic management and fighting corruption. We notice, however, that no one is held accountable when reckless Wall Street speculation plunges the world economy into recession. Nor is anyone held accountable when German automobile manufacturers cheat customers around the world by systematically manipulating the documentation of car emissions. G7 hypocrisy did not start with US President Donald Trump. It was evident long before him – and it has not left the global state with him either.

In the current multilateral system, the G7 are aligned with financial capital and wield disproportionate power. It would be good to have a counterweight. The BRICS are too disparate to serve that function. So far, their big announcements have even largely neglected important issues like the climate crisis. They are unlikely to adopt the kind of coherent agenda that would be needed, not least, because they all want to benefit as best they can from the currently prevailing order. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, moreover, has made things even more difficult than they already were.

Increasingly unstable global order

On the one hand, the other four BRICS members have all condemned Moscow’s aggression. On the other hand, they are eager not to make things difficult for Russia. To some extent, they are trying to benefit from Russia’s isolation, for example by importing its commodities at discount prices. At the same time, the NDB has frozen its Russia programme. The reason is that it wants to keep its western AA+ rating, which shows how limited the BRICS’ range of action really is. How the BRICS as a group will cope with an increasingly unstable global order remains to be seen.

Praveen Jha is a professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi.

praveenjha2005@gmail.com