Civil society

Third point of view

“What we are witnessing at the moment is definitely a turning point,” says Parastou Forouhar, an Iranian artist, author and activist who lives in Germany. The last time Iran experienced major protests was in 2009, after Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, then the incumbent president, was declared victorious in elections. The opposition claimed electoral fraud and started the greatest unrest since the Islamic Revolution, which had ended the monarchy in 1979.

In 2009, “people wanted to know what had become of their votes,” Forouhar said during a panel discussion hosted by the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Frankfurt, Germany. This time, however, the protests lack a common concern, a charismatic leader and a widely-shared demand.

According to Forouhar, young people under the age of 25 are currently the main activists. “This generation wants to achieve something in life, but they see no future.” Their main grievances include corruption, mismanagement and paternalism. The artist says they find “religious laws particularly repressive”. Iran’s government consists of two distinct sides, but many demonstrators do not support either of them. They generally reject the Islamic Republic, Forouhar argues. Observers consider President Hassan Rouhani to be a reformer, whereas the supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, the most powerful man in the state, leads the conservatives. “There is potential for a third point of view, a new opposition,” says Forouhar.

The German-Iranian political scientist Azadeh Zamirirad also speaks of a “turning point in protest culture”. However, the scholar from the German Institute for Foreign and Security Affairs (Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik – SWP) stresses that Iranian civil society is very active, and demonstrations are not unusual. Rather, they are typical of the Islamic Republic. “They are practically part of everyday life,” says Zamirirad. It remains to be seen whether the latest protests will grow into a coherent movement that is entirely independent of the political elites. The Iran analyst recognises three dimensions of the protest:

- Reformers are still pitted against hard-line conservatives, and this conflict was probably the starting point.

- People are rising up because of unemployment, corruption, inflation and precarious livelihoods.

- Outsider groups who are neither affiliated to the reformists nor the conservatives are making their voices heard for the first time.

In response, institutions are changing, Zamirirad has observed. For example, the government is reassessing the freedom of association. A revolution in the form of an armed uprising is not necessary, she says, if civil society gradually obtains more freedom. As an example, the scholar cites the obligation to wear a headscarf, which is becoming increasingly lax. The cloths are becoming more colourful and sliding back. “Millimeter by millimeter, women are fighting for their rights.”

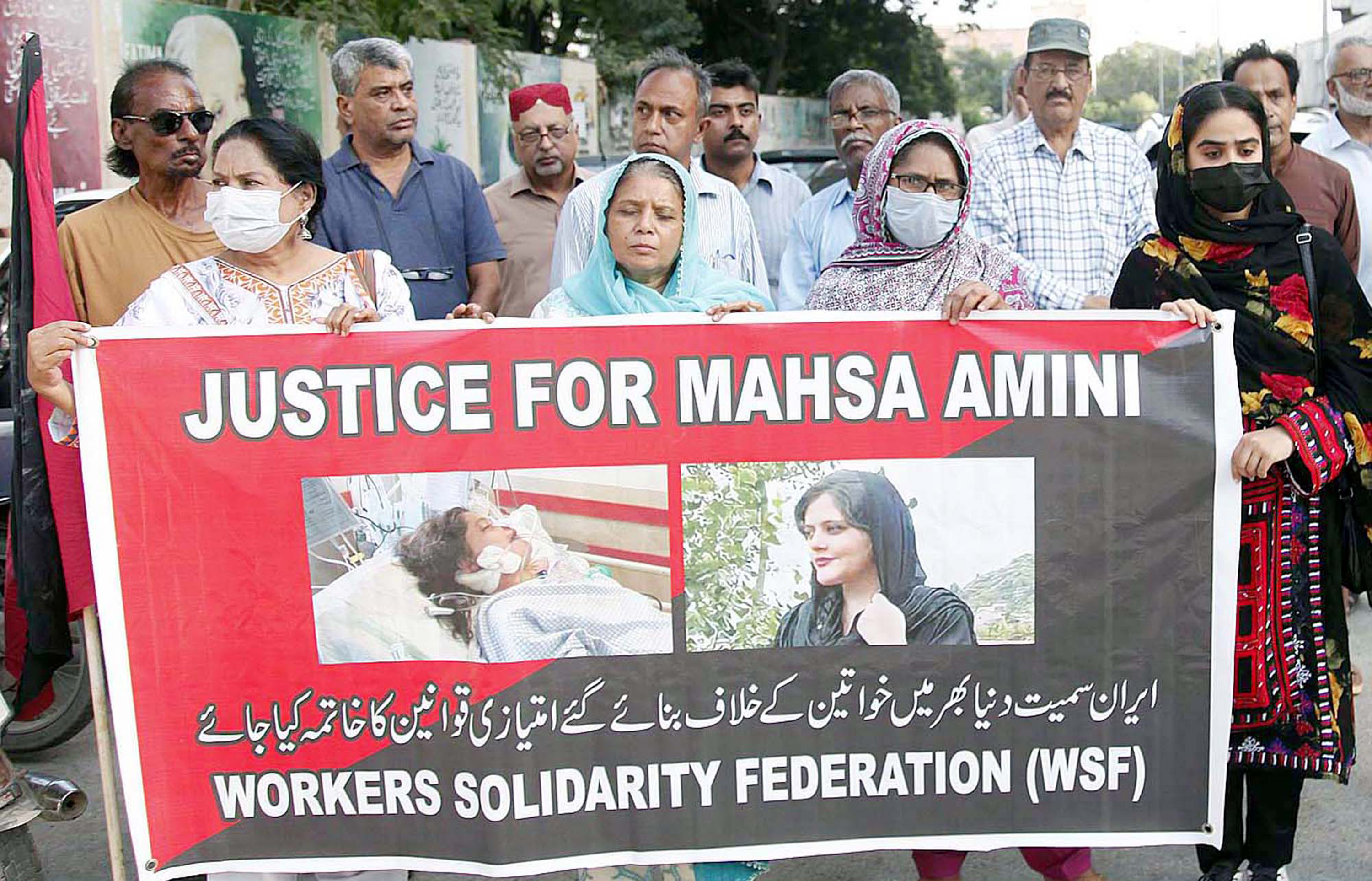

During the protests, some women tore off their headscarves. “That can’t be stopped in the long run.” The mullahs will have to drop the headscarf requirement one day, Zamirirad emphasises. “There is a tradition of a strong women’s movement in Iran - there are more women in parliament than clergymen, you have to let that melt in your mouth.” Forouhar, the artist, agrees that women who protest against the mandatory wearing of the headscarf in public spaces indicate social change.

Vida Movahed started the trend at the end of December. She climbed onto an electrical box in Tehran’s Enghelab Street, removed her headscarf and waved it on a stick. In Forouhar’s eyes, “this is a symbolic picture – because she’s a woman, she’s standing up there, and she’s wearing normal clothes.” Movahed was arrested, but released shortly afterwards. Her action has encouraged others to follow her example. “Even a fully veiled woman in a chador stepped onto an electrical box and waved a cloth,” says Forouhar. “When something like this happens, it inspires hope.”