Climate and biodiversity

To protect life on earth, we must cooperate

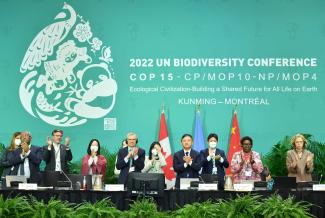

In 1992, the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro adopted UN conventions to tackle the most important ecological problems. Progress has been slow, however. Late last year, there was a global climate summit in Sharm el-Sheikh and a global biodiversity summit in Montréal. Both came close to failure.

In Egypt, delegates ultimately decided to establish a fund to cover loss and damages in poor countries. Unfortunately, not much happened to limit global heating. The conference in Canada made history in terms of adopting the ambitious goal of declaring 30 % of land surface and 30 % of seas protected areas by 2030. So far, only 16 % of land and 8 % of the seas are conservation areas. The need for action remains great, and the stage is set for serious disputes.

Indigenous peoples and deep-rooted local communities live in many areas where nature should be protected. Their interests must not be sacrificed. In Uganda, for example, the Batwa were displaced from their rainforest habitat when the government decided to protect mountain gorillas.

It is therefore good news that the final declaration of the Montréal summit spells out repeatedly that the rights of indigenous peoples must be protected and local communities should be involved in nature protection. Where local people are acknowledged as guardians of nature and supported in that role, both humans beings and nature can thrive. This is the win-win approach.

Global success hinges on developing countries and emerging markets contributing to nature protection. After all, many important ecosystems are on their territory – just consider the rainforests of the Amazon region, the Congo basin or Indonesian islands. Humankind’s future will suffer if the countries concerned, in the pursuit of development and prosperity, destroy nature the way that high-income countries did. The implication is that it serves the latter’s self-interest to do their best in support of sustainable development in less prosperous places.

At the same time, high-income countries must achieve net-zero emissions fast. Global heating must be slowed down. Not only is the climate crisis causing serious suffering in countries that have hardly emitted greenhouse gases. It is also an important driver of the erosion of species and ecosystems.

The double crisis of climate and biodiversity shows that our fates are mutually interdependent. To protect life on earth, we must cooperate. Unfortunately, there is a lack of global solidarity. High-income countries’ lifestyles are unsustainable and cannot serve as the global model. Nonetheless, these countries are not living up to their climate-finance commitments.

Global crises require multilateral solutions. Reckless national egotism, as became evident in Russia’s attack on Ukraine, is unacceptable. Irresponsible action at the domestic level, however, can cause global harm too. Under President Jair Bolsonaro, who lost his re-election bid in Brazil last year, deforestation of the Amazon accelerated to the point that the jungle began releasing more carbon than it is absorbing. In this sense, the Bolsonaro supporters who rioted in Brasília on 8 January were attacking the global common good.

The declarations of Montréal and Sharm el-Sheikh present an opportunity to improve matters internationally. First of all, rich nations must fulfil all promises. The annual $ 20 billion they pledged to less prosperous countries for nature protection must flow reliably and transparently – and on top of previous spending commitments for climate and development purposes.

The nature protection goals for 2030 must be achieved. The natural resources our existence depends on are dwindling. We must protect them as best we can.

Jörg Döbereiner is a member of the editorial team of D+C Development and Cooperation / E+Z Entwicklung und Zusammenarbeit.

euz.editor@dandc.eu