Traditional medicine

Why many Africans must rely on informal health care

Access to affordable modern health care remains a huge challenge in sub-Saharan Africa. Masses of people are too poor to afford treatment at hospitals. Most African countries spell out integrated universal health coverage as a goal. Unfortunately, that goal still seems somewhat utopian in many places. Where government hospitals are supposed to provide services at heavily subsidised rates or even free of charge, facilities tend to be overwhelmed. Indeed, black markets have emerged, as patients often have to pay bribes to get treatment at public health centres.

It matters very much that most Africans do not have any kind of health insurance (see Dirk Reinhard on www.dandc.eu). There is a great need to develop both private insurance and governmental social-protection schemes (see Markus Loewe on www.dandc.eu). So far, however, most health expenditures are paid out of pocket in Africa.

In the few African countries where national medical insurance schemes exist, they serve only a minority, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). In Ghana, only a third of the population receives medical insurance under the country’s National Health Insurance Scheme. In Nigeria, which has among the highest out-of-pocket health expenditures and the poorest health indicators in the world, 75 % of health expenditures were paid out-of-pocket in 2016, according to the WHO.

While there is at least some access to scientifically trained doctors in cities, things tend to be worse in rural areas. Most village communities rely entirely on traditional medicine, and many urban people do so too. The practitioners are easily accessible and their services are comparatively cheap. However, they sometimes fail to diagnose an illness properly or suggest treatments that do not work. Malperformance of this kind can lead to the loss of lives.

Age-old practices

Traditional medicine is also known as ethno-medicine, folk medicine, native healing or complementary and alternative medicine. It is based on millennia of – mostly orally transmitted – experience. Traditional healers are often quite competent when it comes to dealing with standard situations. Bone setters know how to deal with broken bones, for instance, and traditional midwives help women give birth. However, they are not always able to deal with difficult situations. Caesarean sections, for example, are beyond their competence.

A comparative study in Nigeria showed that maternal and child mortality were higher for women who relied on traditional medicine in pregnancy and labour than for those who could afford professional care. Similar studies in Niger and South Africa yielded the same results.

Even faith healers often deliver results, but apart from boosting a patient’s mental state, their practices obviously have not scientifically explainable base. When traditional healers resort to practices with such a base, however, it would be good if they referred complicated cases to modern health centres. Unfortunately, that only happens rarely. To a large extent, modern and traditional medicine co-exist without much exchange between them.

What patients like about traditional medicine

According to research done in Malawi, the traditional healers are not to blame for this state of affairs. “Traditional healers were more enthusiastic than biomedical practitioners, who had several reservations about traditional healers and placed certain conditions on prospective collaboration,” is a finding reported in a joint publication by Fanuel Lampiao, Joseph Chisaka and Carol Clements (2019). While traditional healers clearly had confidence in modern practitioners’ competencies, the reverse was not true.

The study confirmed that one reason traditional healers were so popular was that many live and work in villages, so people need not travel long distances to see them. However, they pointed out that costs and travelling distances were not all that mattered. The researchers found that traditional healers were considered to be more respectful and approachable than their scientifically trained counterparts. They estimated that 80 % of Malawi’s people seek treatment from traditional healers.

Far too often, however, traditional medicine is inadequate. In 2015, malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV-related illnesses killed about 1.6 million Africans according to the WHO. Timely access to appropriate and affordable medicines, vaccines and other health services would have saved many of these lives. The full truth, however, is not only that many patients never saw a professional doctor, but that even if they had done so, they would have been unable to afford the prescribed medications. Over 98 % of the drugs consumed in Africa are produced outside the continent. They are quite expensive, and counterfeit drugs are a problem in their own right (see Assane Diagne’s contribution of 2019 on www.dandc.eu).

The problem with herbal medications

Accordingly, herbal medicine is one of the most important forms of traditional medicine. Once again, it has its limits, even though it often works. Serious issues include that:

- dosage is difficult, so both under- and over-dosage happen,

- sometimes, the wrong plant is used, and

- contamination with toxic substances is common.

Efforts are being made to align traditional and modern medicine better. Over the past two decades, the WHO has been providing financial resources and technical support to ensure safe and effective traditional medicine development in Africa. In a series of clinical trials, 89 traditional products met international and national requirements for registration.

Fourteen countries have thus issued marketing authorisation for herbal medications. About half of these traditional products are now included in national lists of essential medicines. They play their part in treating diseases such as malaria, opportunistic infections related to HIV, diabetes, sickle cell disease and hypertension.

Jean-Baptiste Nikiema is a WHO adviser who specialises in essential medicines. In his eyes, two things are slowing down progress regarding the scientific approval of traditional medicine. One is political interference, the other is researchers’ hesitancy to share insights for which intellectual-property protection is not available.

In most cases, traditional medicine thus remains unregulated in Africa. It is thus not monitored by any institutions of oversight either. Patients deserve better.

Reference

Lampiao, F., Chisaka, J., und Clements, C., 2019: Communication between traditional medical practitioners and western medical professionals. In: Frontiers in Sociology

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8022779/

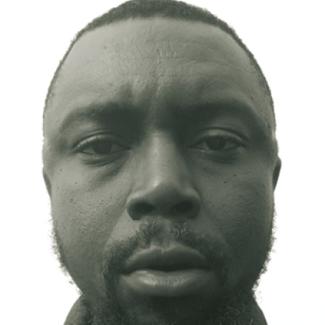

Ben Ezeamalu is a senior reporter who works for Premium Times in Lagos.

ben.ezeamalu@gmail.com

Twitter: @callmebenfigo