Comment

Back in the credit trap

In 2004, Gahna’s exceedingly high foreign debt was cut in half by the multilateral HIPC initiative. The acronym stands for “highly indebted poor countries”, and the debt-relief initiative had been agreed by the G7 summit in Cologne in 1999. An important component was to use freed-up budget resources to fight poverty. Ghana indeed managed to reduce poverty to 50 % below the level of the 1990s.

Unfortunately, the country is now plagued by excessive debt once more. Development was promising at first. In 2007, Ghana was one of only two sub-Saharan countries that managed to issue bonds on international financial markets. The other one was the Seychelles. Among other things, the newly discovered Jubilee oil field off the Ghanaian coast made the country look attractive to investors. In 2011, Ghana’s growth rate of 14 % was the world’s highest. In view of such success, the government was able to take on additional debt in order to tackle development challenges.

Things have since turned sour however. Today, public debt accounts for about 71 % of gross domestic product. That is almost the level of before HIPC.

This development was driven by internal and external issues. Domestically, high wages in the public sector matter a lot. A new compensation system was adopted, and wages have tripled. Ahead of the elections, moreover, the budget deficit ballooned because of a governmental spending spree.

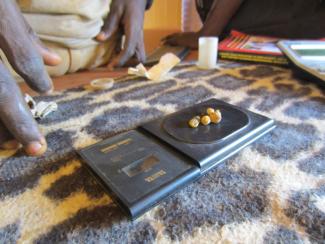

Internationally, dropping prices for Ghanaian commodities like gold and oil have reduced the export revenues the country needs to service its foreign debt. At the same time, prices have soared for import goods that Ghana depends on. It does not produce enough food and petrol. Cheap food imports from the EU have added to the problems by crowding out local farmers.

Today, Ghana’s imports cost more money than its exports generate. Compounding the problems, the exchange rate of the cedi, Ghana’s currency, has considerably dropped. Servicing dollar-denoted debt has thus become even harder. A vicious circle looms should the debt crisis trigger further devaluations.

The government’s response is to take on still more debt. It wants to issue new bonds to service the old ones. The snag is that it must now pay higher interest rates as investors understand its situation.

The country is now struggling with a debt-driven financial crisis. Ghana’s domestic banks are facing liquidity problems. If at all, they only hand out loans to Ghanaian private-sector companies at very high interest rates. Accordingly, private-sector investment has stalled. Ghana’s economy is shrinking; jobs are being cut. At the same time, the costs of living are rising because of the cedi’s low exchange rate. The people are feeling the crisis.

In the eyes of civil-society organisations such as SEND-Ghana, public debt belongs on the political agenda once again. They want the government to act in a transparent and accountable manner. It bothers them that, if money keeps flushing out from the country at recent rates, it will become impossible to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals the UN recently adopted.

HIPC was a one-time affair. The international community still lacks a reliable and well-designed system to resolve debt crises. Developing countries and emerging markets demanded setting up such a framework in the context of the UN General Assembly, but they did not prevail.

However, the General Assembly did agree on basic principles for dealing with debt crises. Germany was one of the few countries that voted against both the framework and the principles. This is a high-risk approach because it weakens the kind of international cooperation we need to prevent debt crises like the one in Ghana. Crises must not be allowed to drag on for years and plunge ever more people into poverty.

Clara Osei-Boateng works for the civil-society organisation SEND-Ghana / SEND-West Africa.

http://www.sendwestafrica.org/

Kristina Rehbein is a political adviser with erlassjahr.de, a debt-relief campaign supported by the churches.

k.rehbein@erlassjahr.de