Labour market

Youth unemployment remains one of India’s great challenges

Pratap Singh has been unemployed for about four years. He is from the Azamgarh District of Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous and under-developed state. Even though he has a college degree in plastic engineering, he is applying for some of the lowest-level government jobs in the Indian Railways. He hopes to get a secure and permanent position even though he is qualified to do far more demanding work.

“As a child, I was told that education would help me get a job, so I studied hard,” he says. However, he now has no job opportunities to look forward to, so applying for a railway job is the best he can do. He often asks himself whether the effort to go to college was worth it: “If education can’t get me a job, then what will?”

Singh’s struggle is not unique. Many members of his generation moved from rural districts to bigger towns in pursuit of degrees in engineering, sciences, law or business administration. But even after graduation, they typically struggle to find employment in their fields of training. Many return home and accept any kind of low-skill work. Singh’s friend Rahul, for example, studied law, but is now working as a low-level office assistant at a local doctor’s clinic.

Singh’s wife is trying to find a job as a teacher at a government school. Such positions are only rarely advertised, however, and when they are, many applicants have the necessary qualifications. To get the job, one must often pay bribes. It is not enough to hand in the appropriate documents. This is the fate of many young Indians in one of the world’s fastest-growing economies.

Labour market development in India

According to the World Bank, India’s gross domestic product (GDP) is set to increase by an annual rate of almost seven percent for the next three years. The growth data for recent years was similarly good. Nonetheless, these figures did not go along with jobs for the millions of young Indians who enter the labour market every year.

Informal settings

A key factor is that much of the growth has been driven by the expansion of India’s services sector, which is significantly less labour-intensive than manufacturing. Most people outside the public sector still work in informal settings. There are only very few formally regulated private-sector jobs with full social protection (health insurance, a pension scheme et cetera). Part of the problem is that about half of India’s people still depend on ailing, small-scale farms.

In cooperation with the Institute of Human Development, an independent Delhi-based think tank, the International Labour Organization (ILO) released a report on the national labour market earlier this year. It noted that more than 80 % of India’s unemployed belong to the young generation. It also confirmed that a majority of those unemployed youth were formally educated. In 2022, two thirds of jobless young persons had graduated at least from secondary schools. Two decades earlier, the respective share was one third. Back then, lack of education seemed to be the core problem.

The report also highlighted that India’s labour market experienced paradoxical progress in recent years. Despite rapidly increasing GDP, a fundamental characteristic continues to be the insufficient growth of formalised economic sectors. They are not able to absorb masses of agricultural workers who need more productive and better-paying work. In the past decade, informal employment in sectors like services and construction was growing faster than farm employment. Since the Covid-19 pandemic, people have been returning to agriculture, however.

The ILO document highlighted widespread livelihood insecurities. The full truth is that 90 % of Indian employment is either self-employment or precarious employment that depends on the employer’s immediate needs and does not offer any guarantees to workers.

In theory, India’s large young workforce should deliver a “demographic dividend”. Economists use that term for a situation where masses of young people drive productive growth without having to take care of many old people and children. High youth unemployment, however, means that there is no demographic dividend. According to the ILO report, inadequate education and lacking skills are to blame. The data show that 75 % cannot send e-mails with attachments, for example, and that 90 % do not know how to apply mathematical formulas to spreadsheets. While more young people complete schools, those schools are apparently not teaching them the right things.

Unsurprisingly, low rates of female labour force participation (FLFP) persist. India’s FLFP is only around 25 %. While there has been some improvement in rural areas, educated young women experience even greater difficulties in finding high-skill work than their male peers. In less developed northern states like Uttar Pradesh, things are particularly tough.

Politics matter

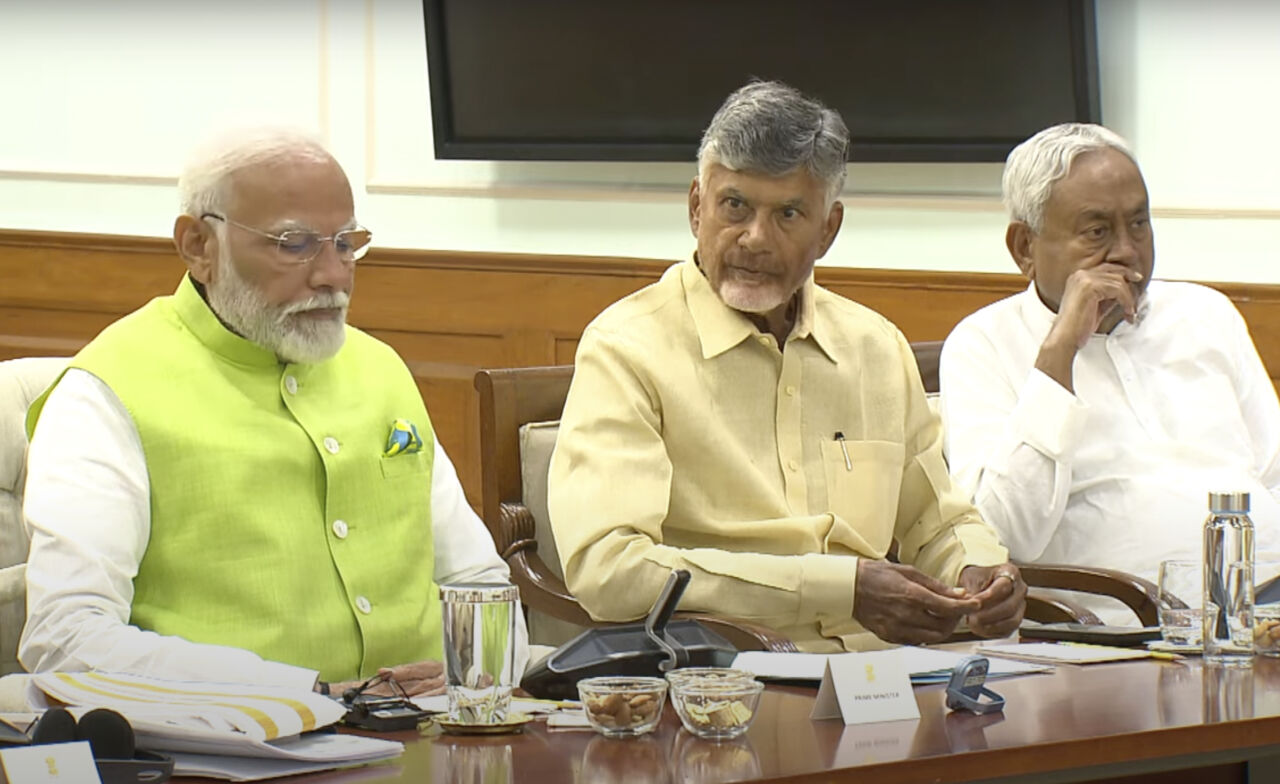

India’s central government rejected the ILO document because of alleged “inconsistency in data”. Given that the report was released shortly before the general elections, this defensive stance was unsurprising. Indeed, there has been a pattern of credible expert work being belittled and refuted by officialdom under Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

As a matter of fact, many polls and surveys showed in recent months that unemployment is indeed a top concern for most young people in India. Some observers say it had an impact on the elections, in which Modi’s party fared less well than had generally been expected. He now depends on parliamentary support from regional parties and can no longer set the agenda on his own.

When he was first elected in 2014, Modi had attracted young people with the promise of creating 250 million jobs over a decade. Ten years later, it is obvious to everyone that his government failed to make that happen.

While India’s economic growth remains impressive on paper, the benefits have not yet reached the young workforce, nor weaker sections of society in general. Unemployment remains one of the biggest challenges the government needs to tackle. It would probably do well to heed the recommendations made in the ILO report. The paper spelled out the “five missions” of

- making production and growth more employment-intensive,

- improving the quality of jobs,

- overcoming labour-market inequalities,

- make skills training and other labour-market interventions more effective and

- close the skills and qualification gaps that keep so many young people stuck in joblessness.

Advancements in artificial intelligence (AI), the report warned, make these missions even more urgent. Technology is expected to disrupt labour markets around the world, and India looks less prepared for the loss of white-collar jobs than the other G20 economies.

Link

ILO and Institute for Human Development, 2024: India Employment Report 2024 – Youth employment, education and skills. Geneva, International Labour Organization.

https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@asia/@ro-bangkok/@sro-new_delhi/documents/publication/wcms_921154.pdf

Roli Mahajan is a journalist based in Lucknow, India.

roli.mahajan@gmail.com