Democracy

Modi won, but no longer looks invincible

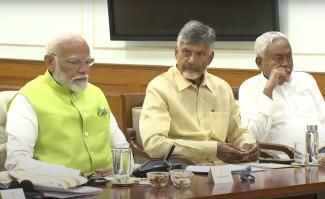

Prime Minister Narendra Modi had boasted that the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), a coalition of parties that supports his Hindu-chauvinist BJP, would win more than 400 of 543 seats in parliament. Instead, the number dropped to 293, only 19 more than needed to return him to office.

Five years ago, the BJP alone had won 303 seats. It was, in principle, to form the government on its own. No longer. Modi does not look invincible anymore. His survival in office depends on two regional parties from now on.

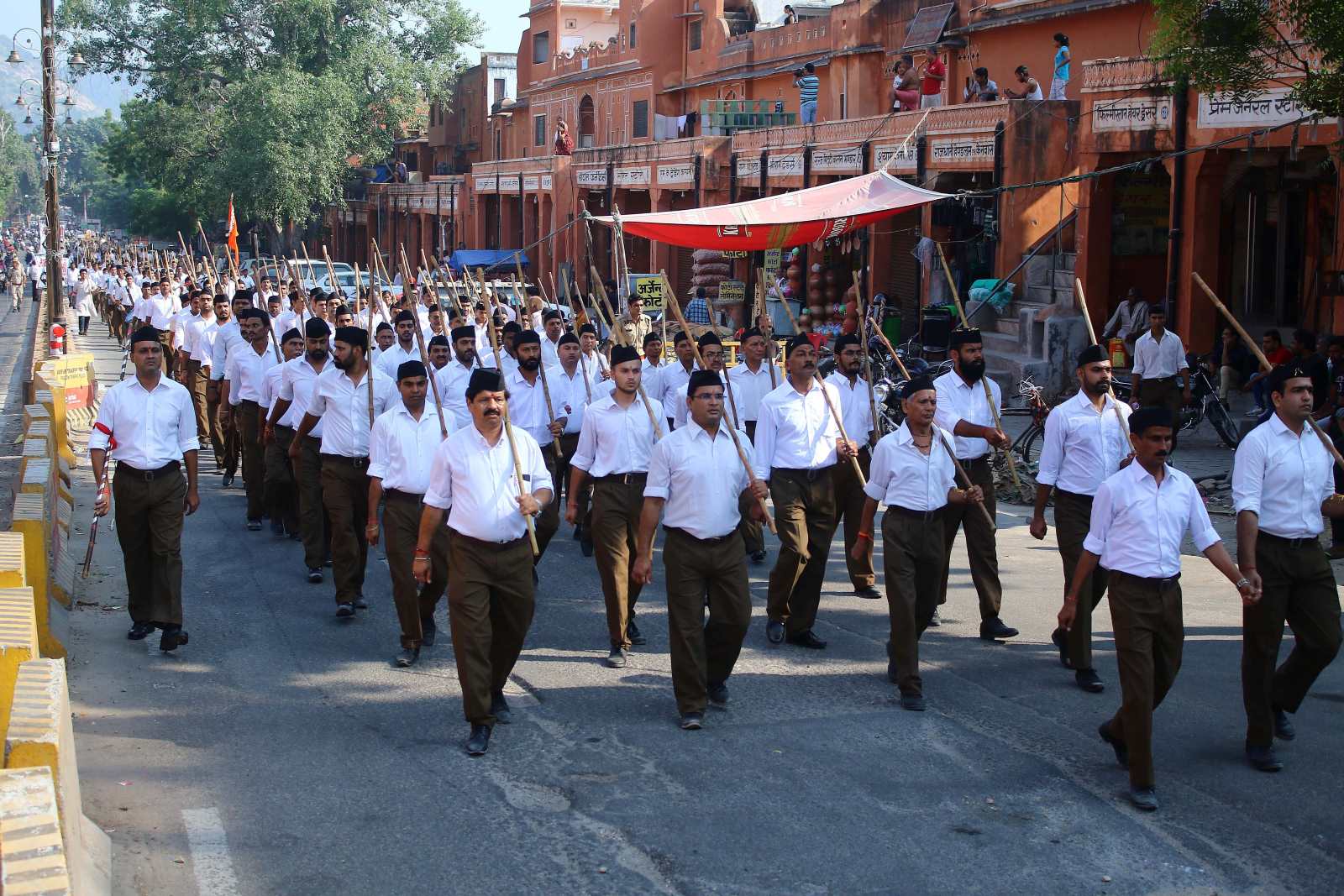

Modi based his campaign on aggressive identity politics. He accused the opposition of favouring Muslims and promised to put Hindus first. Masses of disadvantaged Indians, however, saw through his ploy. Poor Hindus know that they still live in hardship after 10 years of Modi rule. The constant hounding of Muslims, which included brutal lynchings and deadly riots, did not alleviate their socio-economic suffering.

Modi snubbed in Ayodhya

Ayodhya is the striking symbol of this trend. In this north-Indian town, Modi had inaugurated a Hindu temple in January. It had been built on the site of a historic Mosque, the illegal destruction of which by Hindu-supremacists in 1992 had triggered bloody riots across South Asia. The media celebrated the temple inauguration as a moment of national greatness. A majority of citizens in Faizabad, the constituency that includes Ayodhya, felt differently. They snubbed Modi by voting for an opposition candidate from the oppressed Dalit community.

During the campaign, Modi praised India’s economic performance under his government even though masses of people were left behind. He told investors “stability” would serve their interests. When exit polls suggested he would triumph in the elections, the stock market soared. When they turned out to be wrong, it crashed. The Congress Party led opposition alliance INDIA (Indian National Development Inclusive Alliance) now demands an investigation into whether this was deliberate insider trading.

In the past ten years, Modi and his party did what they could to weaken democratic institutions, shifting to increasingly authoritarian rule. Aggressive online agitation pushed that agenda too. Unfortunately, India’s large media houses largely caved into the pressure. Nonetheless, masses of voters have now refuted manipulative identity politics.

A long walk across the nation

Indian politics has always been personalised. Voters appreciate a charismatic leader. Ten and five years ago, the opposition lacked such a popular face. This time, however, Rahul Gandhi, whose father, grandmother and great-grandfather had served as prime ministers, managed to become that face. His rise started with his ‘yatra’, a long walk across the length and breadth of the country in 2022/23. It fit a multi-faith tradition of humble pilgrimage, but also indicated an interest in how people are faring, both in remote rural areas and urban slums.

When Modi’s NDA coalition won in 2014, that was an anti-incumbency vote against Congress Party corruption. The NDA victory in 2019 was an endorsement of Modi, as people hoped he might deliver on development promises. This year’s election did not oust him, but it did reinforce democratic principles.

It would be naïve to underestimate Modi and the vast Hindu-supremacist network his party belongs to. He may be down, but he is not out. An interesting side effect is that the NDA now lacks token minority MPs. There is not a single Muslim, Sikh or Christian among its MPs anymore. That makes the divisiveness of the BJP approach more obvious than it was before.

No democracy is perfect. India’s is no exception. The number of women MPs is 74, not even 14 % of the total. Nonetheless, the election result shows that Indian democracy is alive. It is important to note that poor, marginalised and downtrodden people saved it. They are not interested in a glorious Hindu nation but want their fate to improve.

It is now up to the opposition to keep up the momentum. It must stay focused on issues like social justice, secular governance, civil rights and the public accountability of state agencies.

Suparna Banerjee is a Frankfurt-based political scientist.

mail.suparnabanerjee@gmail.com