Global warming

The need to ratchet

Coordinated action is hard to achieve whenever we are dealing with a public good, especially a global public good. However, as far back as in 1997, the Conference of Parties (COP) of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Kyoto reached an agreement that looked most promising. The Kyoto Protocol, as it came to be called, spelled out mandatory targets for emission reductions in developed countries, but gave them flexibility to determine how to achieve these targets.

One flexible mechanism it defined allowed developed countries to offset their own emissions by investing in emission reductions in developing countries, thus reducing their costs of meeting targets while facilitating development in disadvantaged world regions. The idea was to fix responsibility for historical emissions but also to get win-win actions. Such synergies are still important. Action must certainly take into account, that India emitted about two tonnes of carbon per year and head in 2014, while the respective figure was eight tonnes in the EU – and almost 20 tonnes in the USA. Rich economies, moreover, have more resources than poorer ones.

Nonetheless, the Kyoto Protocol failed. Some major developed countries pulled out of the agreement because governments worried that living up to their commitments would lead to competitive disadvantages. The USA never even ratified the Protocol.

The mistrust arising from this failure resulted in a failure to arrive at an agreed way forward for almost two decades after Kyoto. But climate change continued and, with each passing year, made its mitigation so much harder.

The international community continued to get fragmented and realigned into groups of countries, reflecting vulnerabilities and economic interests. To some extent, these groups overlapped. It proved very difficult to reach political consensus on how to respond to global warming and who must do so. One consequence is that humanity missed opportunities for early action. We have passed several tipping points in recent years. For example, March 2016 was the month in which the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere rose over 400 ppm (parts per million). This is an irreversible benchmark for our lifetimes because emissions persist in the atmosphere for a long time.

High time

Last year, the COP in Paris finally did reach an agreement – but this was when the impacts of climate change were already becoming visible and severe. It was high time. People’s trust in governments’ ability to safeguard their interest was fading and would have been shattered in the absence of a result. The downside, however, is that we still cannot say whether the Paris Agreement will indeed achieve its aspiration of limiting global warming to two degrees at most and preferably even 1.5 degrees above the levels of 1990.

Article 2 of the Paris Agreement spells out these ambitions and provides other key points. It upholds the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in the light of different national circumstances”. Each country will thus determine its level of effort according to the domestic context. Apart from reducing emissions, Article 2 spells out the following goals:

- adapting to climate change and fostering resilience,

- promoting low-emissions development while safeguarding food security and

- ensuring that finance flows serve these purposes.

The problem is that humanity’s chances of staying within the 2.0 degrees limit are currently estimated to be below 66 %. The pledges governments have made so far would actually allow temperatures to rise by even more than four degrees on average! So, what has the Paris Agreement actually achieved?

- First of all, it is the only successful accord since the climate summit in Kyoto in 1997. That, in itself, is important.

- Second, it has asked signatory countries to state what they will do to protect the climate. It is hoped that, in sum, these intended nationally determined contributions (INDCs) will eventually suffice to protect the climate.

- Third, the agreement invites countries to ratchet their INDCs in the context of future COPs in order to bridge the gap between goals and commitments.

This approach can work out, but there are serious doubts that it will. As pointed out above, the INDCs made to date are totally insufficient. Considerable ratcheting up will be necessary, and there is no guarantee that will happen. The revision and upscaling of the INDCs is scheduled for 2020 – and four years are a long time in view of our fast changing climate. Another worry is that INDCs may contain misleading and politically motivated information. Moreover, it is well understood that the baselines of the business-as-usual scenario that was used in Paris were too optimistic. Global emissions have already exceeded it. Part of this problem arose because the assessment reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) were still not forceful enough to convey the full drama. All in all, the IPCC has helped to drive the debate (see box).

There is good news, however. The INDCs are a meaningful first step towards building a coherent international emission-reduction system. They go beyond what most countries would have done anyway. Moreover, the Paris Agreement has come into force within eleven months, having been ratified by a large number of countries in record time.

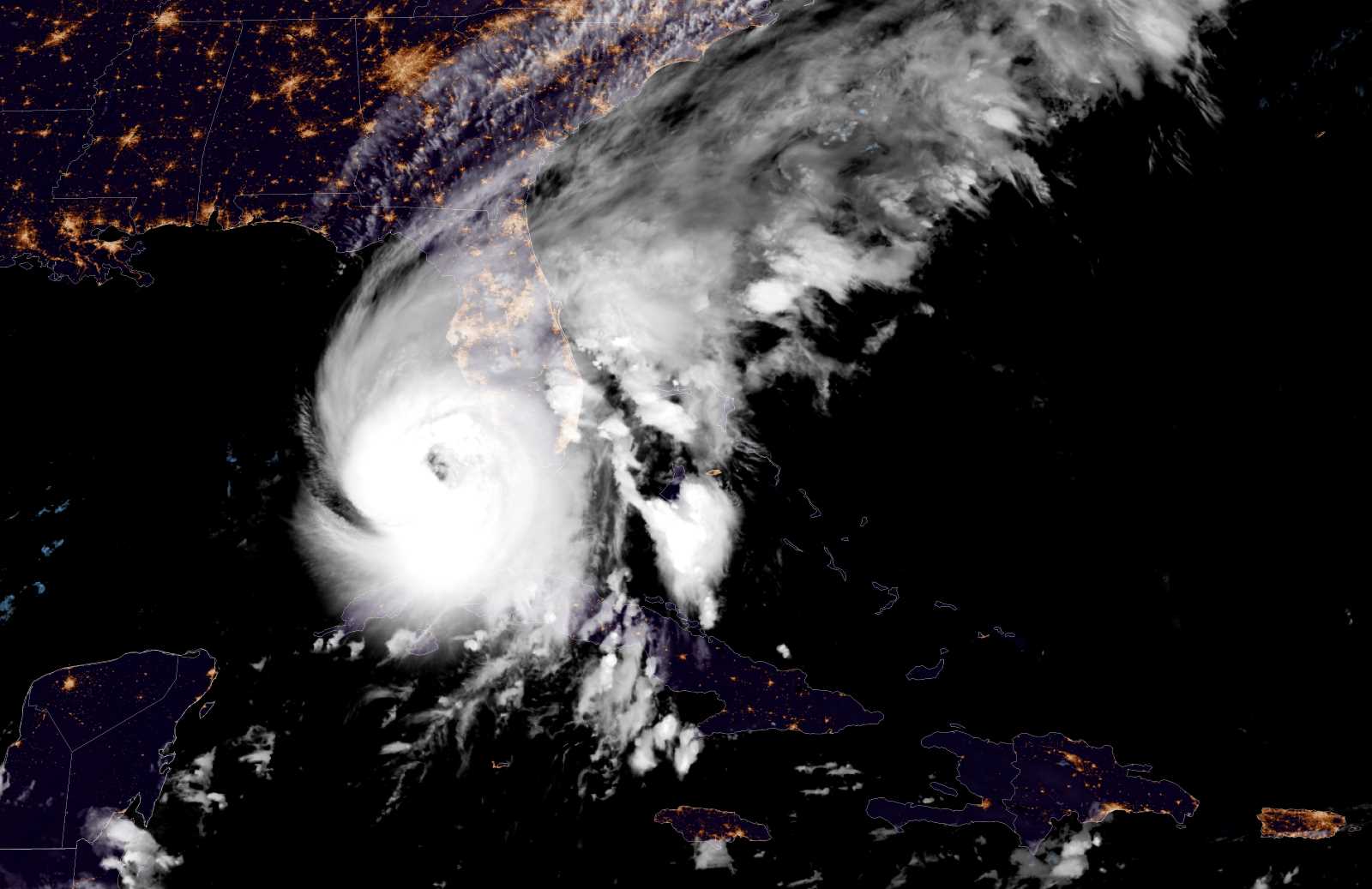

Policymakers are more likely to act if they see how global warming affects their countries in regard to food security, health, storm hazards and other issues. It will also help if they understand the economic opportunities of climate protection in terms of new jobs, new industries and economic growth. The more synergies are found, the easier it will be to protect the climate.

Even without the kind of mandatory national targets envisioned in Kyoto, the need for international cooperation remains great. If INDCs are to become as strong as needed, the capacities and institutions of developing countries must be strengthened. All countries must become able to draft and implement appropriate policies, and that requires capacities for research and analysis.

International cooperation on climate change is the result of many complex motivations. The greater the cooperation the greater their trust and confidence in each other. The question is: how can this international cooperation be made more effective? Further scientific research can help, but governments must certainly get their act together with the right policies and incentives.

Leena Srivastava is the vice chancellor of TERI University in Delhi.

leena@teri.res.in

Arun Kansal is a professor at TERI University and currently on deputation leave.