Governance

How fossilised, power-hungry men keep Africa in a stranglehold

At the beginning of July, Paul Biya, the 92-year-old president of Cameroon, announced his intention to run for an eighth term in the elections scheduled for October. Biya has been president for 43 years – since 1982. He served an additional seven years as prime minister (1975–1982), which means that he has been in power for a total of 50 years. He is in poor health and, at a recent US-Africa summit, did not know where he was when he was led onto the stage to make a statement.

The reality is that at 92, Biya is no longer capable of governing a country, even if he and his supporters claim otherwise. He asserts that his decision to run for re-election is motivated by the Cameroonian people’s demands for him to continue his leadership and by his determination to tackle his country’s pressing problems.

At the end of July, another African head of state, the 83-year-old President of Côte d’Ivoire, Alassane Ouattara, announced that he would run for a fourth term in the elections also scheduled for October. Ouattara, who had amended the country’s constitution already in 2016 to remove term limits, has been president since 2010. Like Biya in Cameroon, he was previously his country’s prime minister (1990–1993). And like Biya, Ouattara claims that his decision to run for re-election is a response to the demands of the people.

Biya and Ouattara are part of a long line of presidents who have been in power since the 1960s, the decade of Africa’s independence from colonial rule. Other examples of incumbent African presidents who have been ruling for years and have no plans to step down include Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea, who has been in power since 1979, Denis Sassou Nguesso of the Republic of Congo, in power since 1979 (with a brief interruption between 1992 and 1997); Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, in power since 1986; Isaias Afwerki of Eritrea, in power since 1993; Paul Kagame of Rwanda, in power de facto since 1994; and Ismaïl Omar Guelleh of Djibouti, in power since 1999. The six longest-serving African presidents still at the helm have collectively ruled for 211 years.

They follow in the footsteps of other long-serving former presidents, including Muammar Gaddafi of Libya (42 years), Omar Bongo of Gabon (41 years), Gnassingbé Eyadéma of Togo (38 years), José Eduardo dos Santos of Angola (38 years), Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe (37 years) and Dawda Jawara of Gambia (30 years). Many other African presidents were in power for between 10 and 20 years before they died, were violently overthrown or voted out of office.

Racist European exceptionalism?

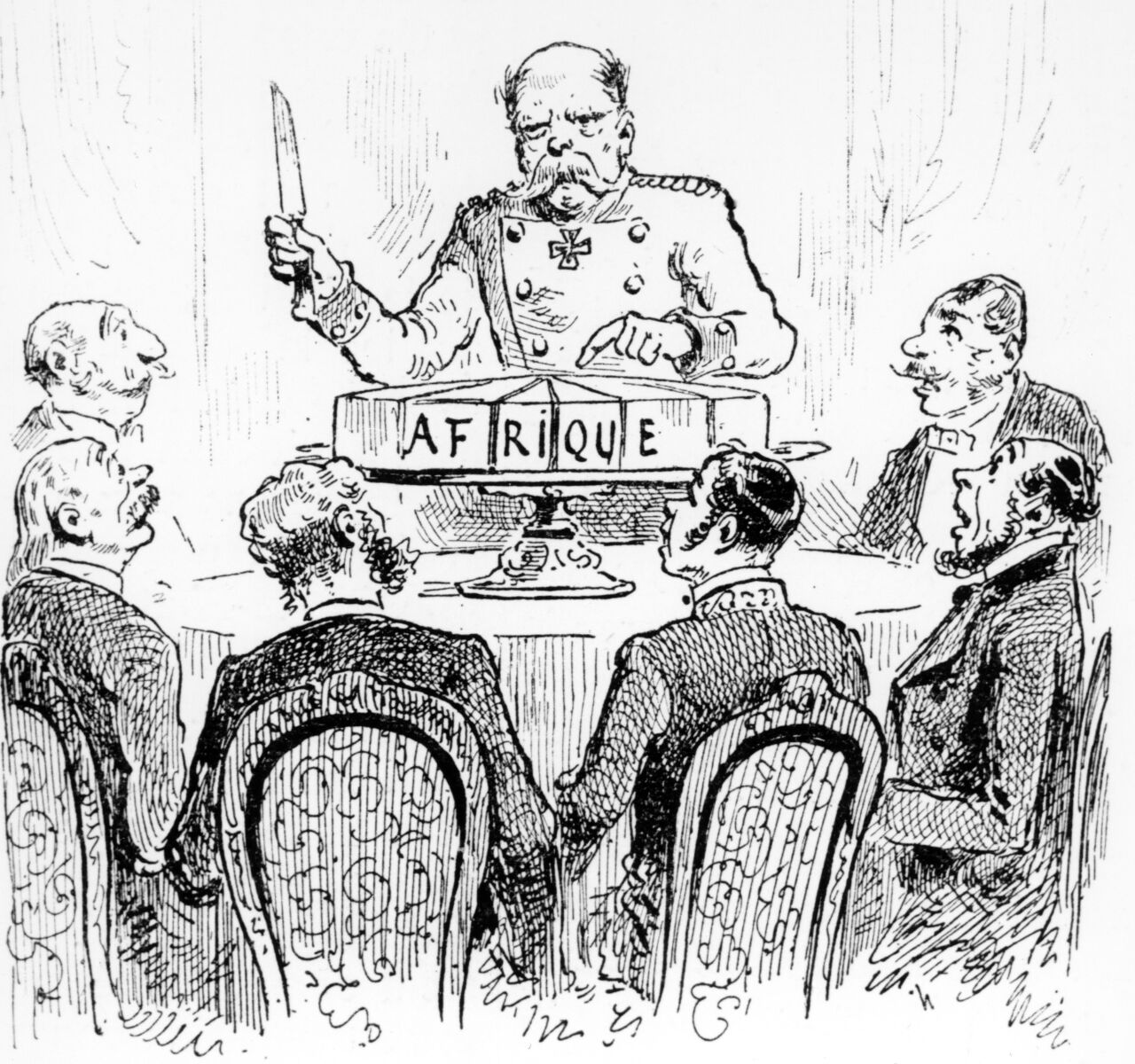

The tendency of African heads of state to cling to power has deep roots. During the struggle for independence, European colonisers often told African nationalists that their people were incapable of governing themselves. Some colonisers argued that Western forms of government, which had been newly introduced to African colonial territories and still lacked some basic institutional structures, were unsuitable for independent African nations.

African nationalists, most of whom soon became leaders of newly independent African countries, condemned such attitudes as racist European exceptionalism that had no basis in reality and aimed to deny African peoples their right to self-determination, as enshrined in the Atlantic Charter (1941) and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). Invoking the provisions of these two international guarantees, nationalist leaders insisted on self-determination for their countries and ultimately achieved it.

However, once in power, some former nationalist leaders, now presidents of the newly independent countries, proved the European colonisers right as they transformed their states according to a kind of African exceptionalism. They now claimed that Western forms of democratic governance and ideas of human rights were alien to Africa.

Instead of opening up the political space to allow dissent and promote free debate about the best path for the newly independent countries, the new leaders suppressed, imprisoned, killed and exiled their opponents, gagged the free press that had actually helped them rise to power, and ignored the needs of the masses who had voted for them. They proclaimed hollow, pseudo-ideological notions of “Africanity” and “authenticity” to justify their newfound contempt for the concepts of equality, the rule of law and political accountability. In other words, they denounced the very concepts they had fought for during colonial rule as subversive tools of neo-colonial imperialism that had no place in an independent Africa.

Notions of the divine right of kings and the sacred duty of subjects to obey their rulers predated and survived the historically brief period of colonial rule. The new African leaders would have had to change these pre-colonial notions of governance to adapt them to the new nation-state systems introduced with independence, in which power lay with the people. Such a transition would have enabled the emergence of a politically enlightened citizenry capable of holding their leaders accountable. Unfortunately, in many cases, civic cultures were never transformed, which explains why notoriously corrupt and repressive African leaders are able to continue winning elections and hold on to power, with only a small percentage of their populations publicly protesting against them.

Backed by the blind support of many people, some of the most prominent former champions of African rights and freedoms soon declared themselves presidents for life and introduced one-party states. They simply suppressed dissenting opinions and clung to power for as long as they lived. This was the case with Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana, Ahmed Sékou Touré in Guinea, Hastings Kamuzu Banda in Malawi, Gnassingbé Eyadéma in Togo and Omar Bongo in Gabon. Today, one-party states and life presidencies are rarely openly declared. They have been normalised through regular sham elections in which people are supposed to vote for leaders who are allegedly chosen by God and supported by a corrupt transactional politics of patronage and oppression.

Proxy battlefields in the Cold War

Africa’s post-colonial leadership crisis was exacerbated by the fact that the continent gained independence at the height of the Cold War. Caught in the midst of this global ideological conflict, Africa’s newly independent countries became metaphorical proxy battlefields in the bitter contest between communism and capitalism. Although a group of these countries joined forces with several Asian countries to form the Non-Aligned Movement after the 1955 Bandung Conference, true neutrality was simply impossible in the face of the aggressive policies of global ideological dominance pursued by the Eastern and Western power blocs.

The situation threatened Africa’s future. Autocratic and corrupt leaders received blanket support or were otherwise propped up as long as they professed allegiance to one ideology or another. At the same time, subversive activities such as military coups, secessions and political assassinations were sometimes encouraged or even financed by Moscow or Washington and their respective allies. The result was a flood of coups, civil wars and political murders that continued to plague the continent long after the end of the Cold War.

At the same time, the new heads of state were busy securing their power and dependent on the unconditional support of their allies in NATO and the Soviet Union. They also had their eye on the financial incentives offered by the Bretton Woods institutions – the IMF and the World Bank. Without giving much thought to the long-term consequences of unnecessary and unlimited borrowing, the new African countries soon found themselves in a debt trap from which they are unlikely to escape any time soon.

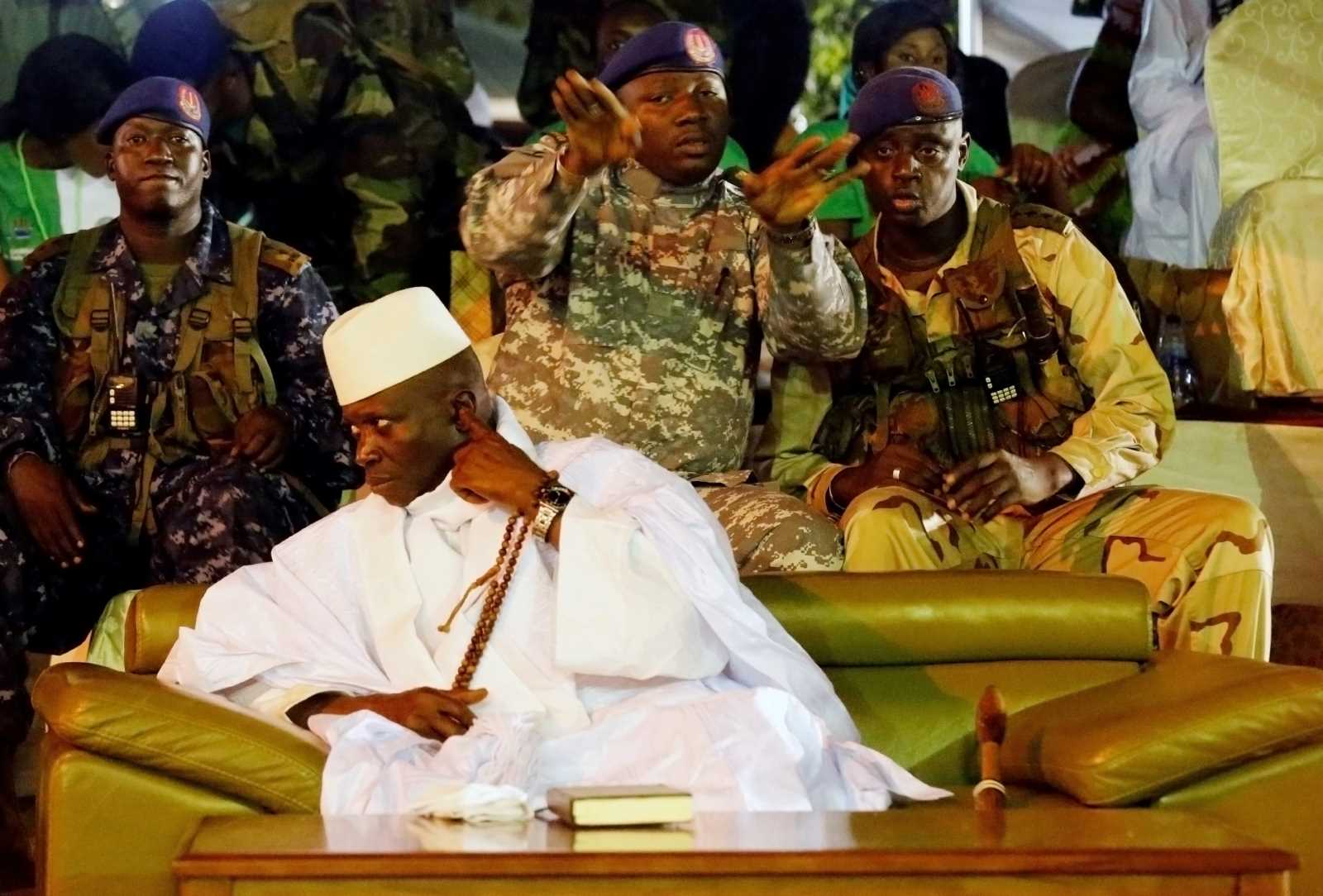

Many of today’s African heads of state, who feed off corruption and depend on the boots and weapons of their military, continue to wage war against dissenters in their own countries, neglecting what needs to be done to promote sustainable development. They still see no need to transform their countries’ pre-colonial civil culture into an active and participatory civil culture that corresponds to the nation-state systems introduced after independence. Instead, they maintain the structures but ignore the essence of the nation state – an anomaly that allows them to abuse and cling to power while oppressing their people with impunity.

Baba G. Jallow was the inaugural Roger D. Fisher fellow in negotiation and conflict resolution at Harvard University’s law school (2023-2024) and the former executive secretary of Gambia’s Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC).

gallehb@gmail.com