Governance

In West Africa, authoritarian attitudes go back to colonial rule

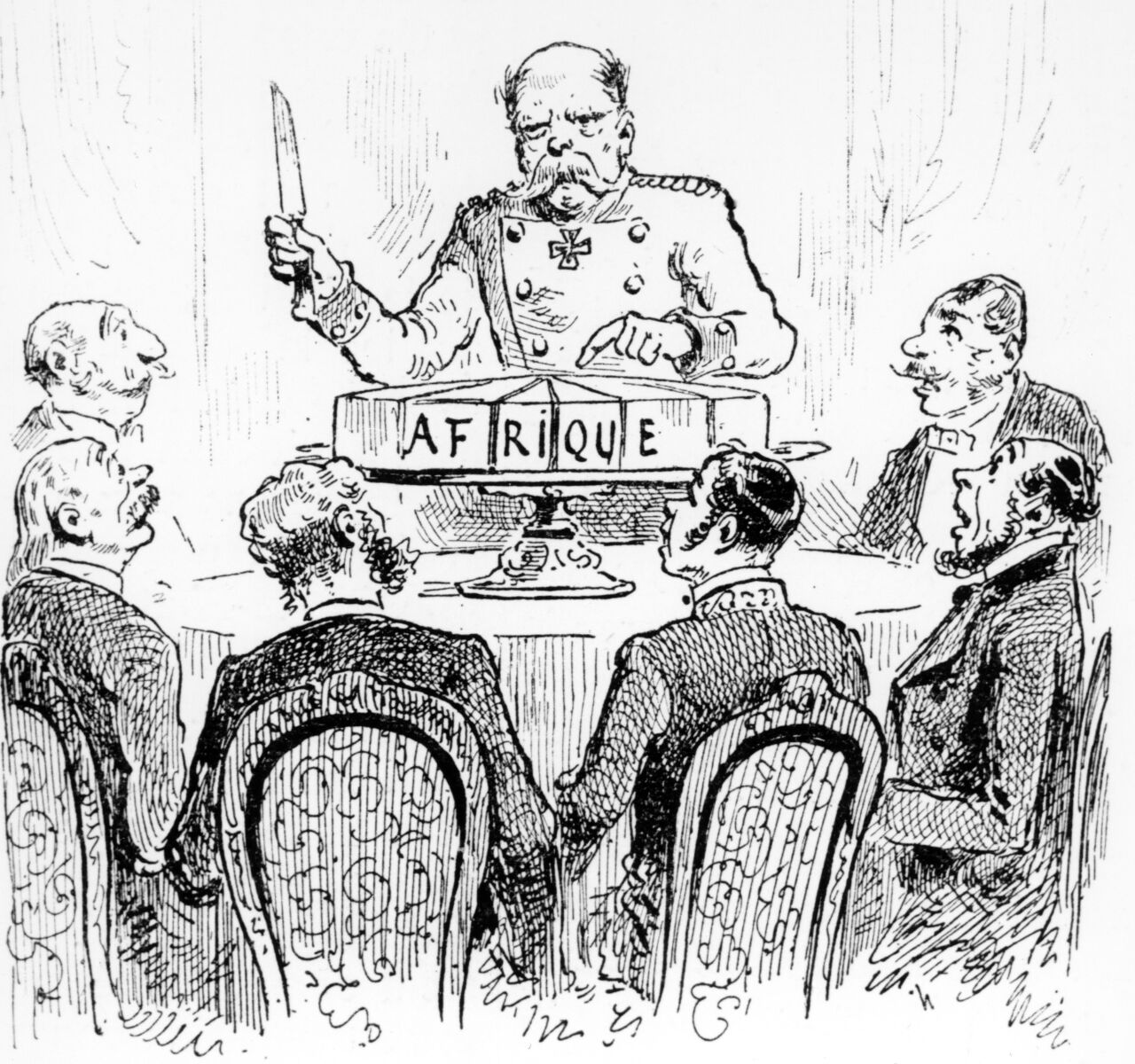

In the late 19th century, European powers partitioned Africa and set up colonies. Britain and France established their rule over West Africa. The tiny exceptions were Portuguese colonies, which are now Guinea-Bissau and Cabo Verde.

The colonial powers used a combination of blatant subterfuge and naked force. They made African rulers sign “treaties of friendship and protection” and thus transferred the control of entire kingdoms and chiefdoms to Europe. Where African rulers disagreed, the colonial powers used military force. Either way, colonialism served extractive interests.

The British and French forms of domination were not identical, but ultimately quite similar. Britain used the term “indirect rule”, while the French spoke of “assimilation”. Both concepts were built upon the idea of Africa being a dark continent that needed the light of western civilisation.

The British claimed that the best way to govern Africans was through their own traditional systems of governance. By supposedly allowing Africans to rule themselves, though under British control, traditional customs were supposed to be preserved.

This claim was hollow. For one thing, only African rulers who pledged total submission to British hegemony were allowed to stay in power. Those who resisted were removed, and the colonial masters replaced them with “warrant chiefs”, who were often persons of low status in African society, and sometimes even outcasts. These persons would normally never have come close to positions of leadership.

The French appointed chiefs, who were called “chefs de canton” and resembled Britain’s warrant chiefs. The main function of both were:

- the collection of taxes for the colonial administration,

- the regulation of trade and

- the maintenance of what was called law and order, but really only served the dominance of the colonial power.

Unaccountable administrators

Warrant chiefs and chefs de canton were salaried servants of the colonial administration. They did not owe their authority to the Africans they ruled, but to the colonial authorities that appointed them. They could be sacked and replaced at will. At the same time, they could expect their supervisors to only interfere minimally in local affairs. They actually wielded more power than precolonial predecessors had been afforded. The warrant chiefs and chefs de canton were unaccountable to the people and not constrained in any way by traditions of consultation, which, for example, had given elders or faith scholars considerable influence in community affairs.

Some historians argue that the warrant chiefs were actually more powerful than the chefs de canton. Most likely, power relations varied from place to place. There were very few essential differences between British and French colonial policies.

Both London and Paris had racist notions of European superiority and claimed to be on a civilising mission. The ultimate objective, however, was empire building and the extraction of African resources.

Taxpayers in the imperial centres were unwilling to pay for the administration of far-flung colonies. “Indirect rule” was therefore built on the rationale that African colonies had to finance their own administrations through trade and taxation.

Assimilation without citizenship

The situation was basically the same in French-controlled West Africa. French assimilation, however, was built on the notion that Africans not only needed western civilisation in general but would benefit in particular from the superiority of French language and culture. Unlike the British, the French wanted Africans to become French citizens in order to be fully human. Nonetheless, the idea of French citizenship for all African subjects suffered a stillbirth.

Had all French colonial subjects been granted full citizenship, the French people would have become a minority in their own country. An African candidate could easily have won a presidential election, and the French parliament might have seen a majority of African members. Obviously, neither possibility was acceptable to the imperial power.

Only four African municipal areas, called “communes”, became fully French: Dakar, Goree, St. Louis and Rufisque. All are in what is now Senegal. Their people were made full citizens, but all other Africans under French rule remained subjects without voting rights nor other benefits of assimilation.

When it came to administration, the French were more direct in abolishing African systems of governance. The British hid behind the mantle of indirect rule and to some extent kept relying on African structures. The French abolished such structures and replaced them with cantons and prefectures. These administrative entities mostly survive unchanged to this day.

Arbitrary borders

What further undermined traditional African governance systems was that few of the chiefdoms or kingdoms survived the European carve-up in their original form. The boundary makers split African communities and ethnic groups indiscriminately. People who spoke one language and shared one culture found themselves under different colonial powers. Both Britain and France, of course, relied on their own language, their own legal system and their own administrative concepts.

The impact is still felt today. Wolof, for instance, is spoken in Senegal and Gambia, Ewe in Ghana and Togo and Haussa in Niger and Nigeria. Senegal, Togo and Niger use French for official purposes, the other three countries use English. There are many more examples of arbitrary colonial borders splitting ethnic communities in two.

The borders that were drawn arbitrarily remain dysfunctional today. Supranational organisations like the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the AU have not done much to improve matters. Citizens of ECOWAS members may now hold an ECOWAS passport, for example, but the movement of both people and goods across borders remains difficult. Taxes must be paid and permits, which are issued by customs and immigration authorities, procured. Different languages, currencies and laws complicate things. Capricious border controls similarly obstruct travel, commerce and educational transactions.

In the eyes of West African governments, rigid notions of sovereignty remain almost sacrosanct. Moreover, policymakers all too often feel entitled to unlimited power and, like the colonial masters before them, give the public rather little say in public affairs. The sad truth is that the ghosts of European colonialism still haunt West Africa – as well as other parts of the continent.

Baba G. Jallow is a historian and a former executive secretary of Gambia’s Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC). He is a member of the AU’s Continental Reference Group on Transitional Justice.

gallehb@gmail.com