Colonialism

The Scramble for Africa

Before 1880, European influence in Africa had mostly been limited to the continent’s coastal areas. By 1900, almost the entire African landmass was under European overlordship.

The transformation was drastic and near-permanent, indefinitely sealing the fates of millions of people. Britain and France built the largest empires in Africa, but countries like Belgium, Germany, Portugal and Italy had colonies too.

The scramble was entirely driven by European interests. Economically, the end of the Atlantic slave trade coincided with the industrial revolution in Europe. The growth of the factory system led to increasing demand for raw materials. The production of surplus goods meant that foreign markets were needed too. The generation of excess profits, moreover, required new investment outlets.

A strong sense of nationalism had gripped Europe after Belgium, Italy and Germany were established as nation states. Their aspirations to build empires caused insecurity in Britain and France, especially after the latter’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71.

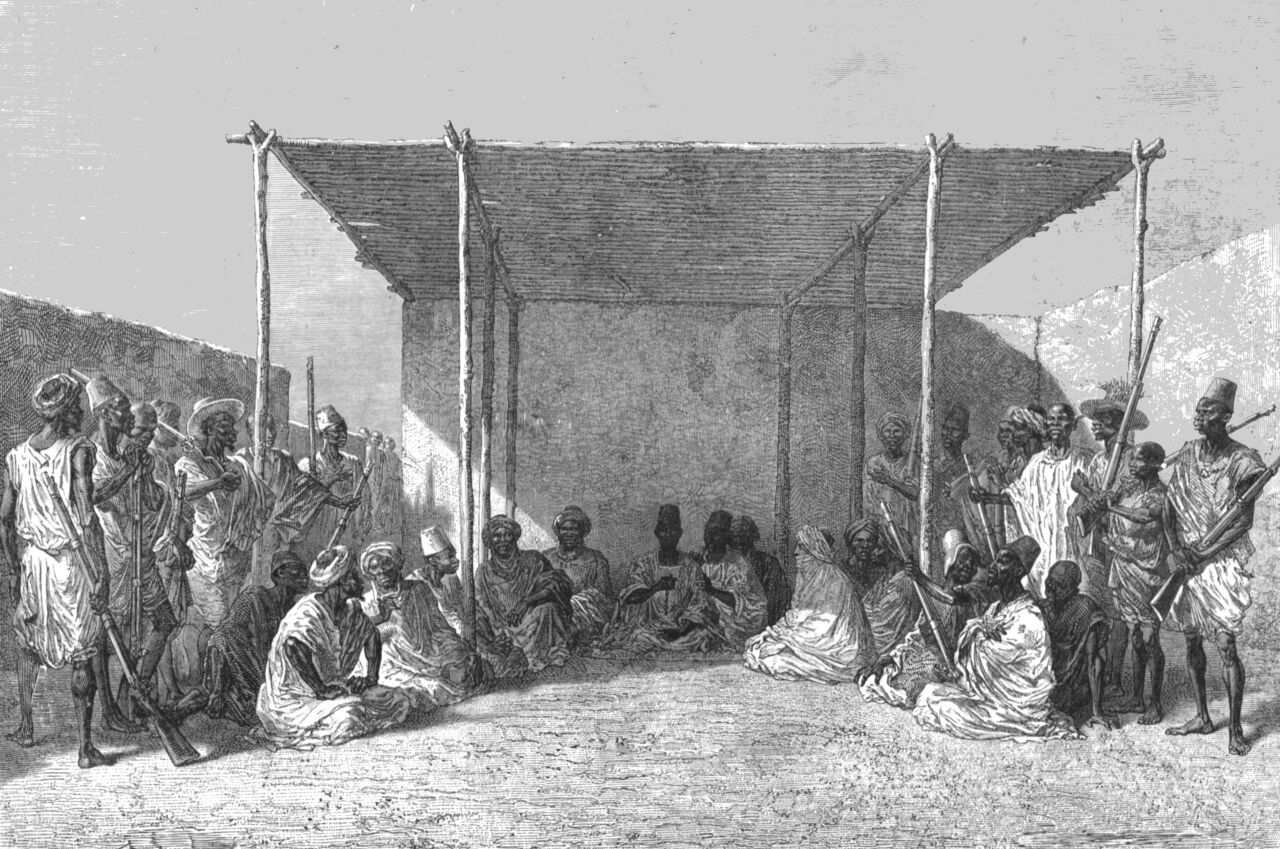

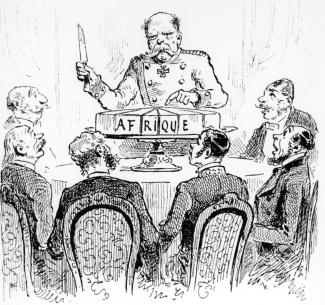

Not a single African was present when the continent was carved up

The rush to grab African territories could easily have led to war. German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck averted that risk by convening the infamous Berlin Conference from November 1884 to February 1885. The event served the imperial powers to divide the African continent among themselves. Not a single African individual was present – nor was a single African territory represented. The concerns of African people did not matter. The imperial powers defined the rules of partition and carved up the continent.

One rule was that, when any European power intended to lay claim to African land, it had to inform the other powers immediately. Any counter claim was to be settled amicably. The colonial masters also agreed that annexation of an African territory by a European power had to be followed by occupation and the establishment of administrative structures.

It was also agreed at Berlin that all European powers were free to extend their spheres of influence and control as much as they could as long as they did not encroach on the sphere of another European power. Finally, all European powers were declared to be free to navigate the Congo and Niger rivers without hindrance. European bickering and skirmishes over that right had been a key catalyst for the Berlin conference.

Baba G. Jallow is a historian and a former executive secretary of Gambia’s Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC). He is a member of the AU’s Continental Reference Group on Transitional Justice.

gallehb@gmail.com