International financial architecture

Better development financing for Africa

Africa’s importance for the world and particularly for Europe has grown enormously in recent years. The continent has a population that is comparable to that of India or China, and it is still growing quickly. It could become a future market that will comprise a quarter of the world’s people in 25 years. Africa is rich in natural resources, especially those that are needed for the energy transition, and it is well-suited to the climate-neutral production of hydrogen. At the same time, Africa remains economically weak in general and is home to about 60 % of the world’s extreme poor, according to World Bank data. Given that economic development is based on investments and their financing, Africa should be supported with more capital, and development financing should be expanded accordingly.

The UN recently added its own recommendation to the numerous initiatives to improve Africa’s capital resources (UN 2023). It was discussed at the Summit of the Future co-facilitated by Germany and Namibia at the UN in New York in September 2024. Essential components of the recommendation were incorporated into the UN Pact for the Future, which was adopted at the summit.

The recommendation to reform the international financial architecture does not only apply to Africa, but nevertheless it contains elements that are immediately relevant to Africa’s development. In the following, we will concentrate on two reform areas that relate directly to development financing: debt and international financing.

Africa currently has a strong interest in reforms in these areas. Numerous countries on the continent are overindebted or soon will be, meaning that a solution to this problem is urgently needed. Africa’s scanty capital resources are under increased pressure due to the cost of a climate-neutral transformation of the economy and measures to adapt to climate change.

Crushing national debt

The UN’s recommendation contains suggestions for improvement in three areas:

- providing information to prevent over-indebtedness,

- lowering interest rates to prevent crises and

- restructuring debt to resolve crises.

The critical debt situation of many countries of the global south is a recurring and predictable phenomenon. Often it is triggered by unfavourable macroeconomic circumstances, like global economic shocks. It is widely known that these situations can occur.

Consequently, international debt policy must take such scenarios into account in order to avoid over-indebtedness. Instead, there keep being new reasons to further increase the credit volume. It would certainly be helpful to provide all parties with better information about existing loans – as the UN paper recommends – but ultimately this remains the decision of the borrowing country and its creditors.

The aforementioned parties clearly have incentives to agree on loans that are too often too risky. To counter this trend, African countries need more independent monitoring institutions. Unfortunately, poorly functioning institutions are both a cause and an expression of a lack of development. Breaking through this negative cycle is difficult. Creditors also have a great deal of responsibility here.

The UN further proposes limiting interest payments. They are always a burden, even though actual development loans are usually granted with an interest rate of only around two percent over a 40-year period. Other loans are more expensive, including those granted by China. Loans at market conditions are even more costly.

The UN paper further recommends making a clearer distinction between liquidity crises (when long-term affordable financing can be the solution) and solvency crises (when debt write-downs may be needed). The UN argues that if interest rates had not been raised during times of crisis, but instead had been kept low, debt crises would not have occurred in many cases. These calculations are very hypothetical, however. The assumption is that the entire macroeconomic policy would remain unchanged. But is that realistic? Wouldn’t lower interest rates lead to additional debt and ultimately to a solvency crisis on a larger scale?

In 2020, the G20 introduced the Common Framework for Debt Treatments (CF) in order to involve more lending countries – including China – in efforts to address over-indebtedness than the leading western countries that made up the “Paris Club” at that time. As the largest bilateral creditor to developing countries, China typically rejects debt forgiveness, meaning that countries’ debts get extended, but ultimately only deferred – not resolved (Horn et al., 2023). This problematic approach could impact numerous countries in Africa, where China has frequently provided over 25 % or even 50 % of public debt.

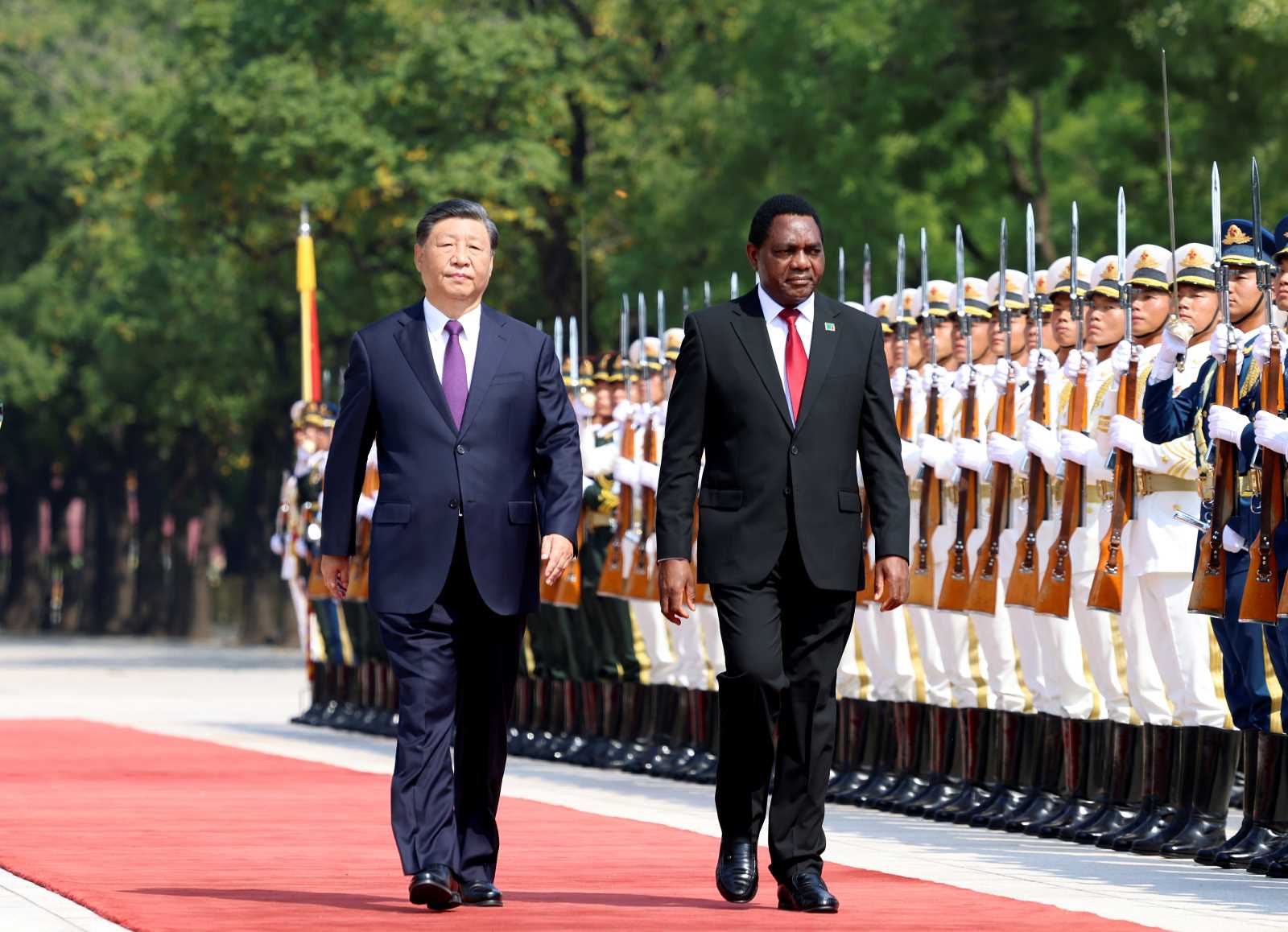

However, the recent agreement with Zambia as part of the Common Framework has raised expectations for the first time that China will participate in substantial debt relief too. Efforts to avoid isolating China and instead include it in potential solutions can therefore be successful, despite creditors’ differences.

Expanding international development financing

Unresolved repayment conditions make it almost impossible to grant new loans. Yet fast-growing African economies have a great need for capital. In the aforementioned UN document, many detailed proposals are linked to demands for more affordable loans and non-repayable grants.

There are good reasons to adhere to traditional poverty- and growth-oriented development financing. In sub-Saharan Africa, the share of absolute poor with an income of less than $ 2.15 per day in purchasing power parity remains fixed at over one third (Baah et al., 2023). Moreover, social indicators like quality of education are still very low, which points to an ongoing need for traditional development cooperation.

Activating private creditors

To reduce currency risks for developing and emerging-market countries, the UN recommends that a larger share of loans be issued in local currencies. Since the need for capital to protect global public goods far exceeds the capacity of public institutions, the UN demands that public development financing should be used more strategically in order to activate private capital flows (“blended finance”).

Though the high need for capital for global public goods is widely recognised, it is unclear whether the proposed expansion of public development financing will succeed. For one thing, in many situations it is debatable whether current funding is being used effectively. It is doubtful to what extent the governments of partner countries could productively use additional financial resources to the proposed extent, for instance for measures to adapt to the climate crisis. For another, given the current political situation in many donor countries, majorities in favour of a significant increase in development funds can hardly be counted on. The ongoing budget negotiations in Germany are one example.

Independent from the UN recommendation, European development policy should examine its own development financing and adapt it to a changed reality.

References

UN, 2023: Reforms to the international financial architecture. Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 6.

https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/papers/10.18356/27082245-29

Horn, S., Parks, B. C., Reinhart, C. M. and Trebesch, C., 2023: Debt distress on China’s Belt and Road. AEA Papers and Proceedings, Vol. 113, May 2023, S. 131-134.

Baah, S. K. T., et al., 2023: September 2023 global poverty update from the World Bank. World Bank Data Blog.

https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/september-2023-global-poverty-update-world-bank-new-data-poverty-during-pandemic-asia

Lukas Menkhoff is a senior researcher at the Research Center “International Development” of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, professor emeritus of economics at the Humboldt University of Berlin and member of the Finance Group at HU Berlin.

lukas.menkhoff@ifw-kiel.de

Rainer Thiele is a professor of development economics and the deputy head of the Research Center “International Development” of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy. He is the director of the Kiel Institute Africa Initiative.

rainer.thiele@ifw-kiel.de