Glossary

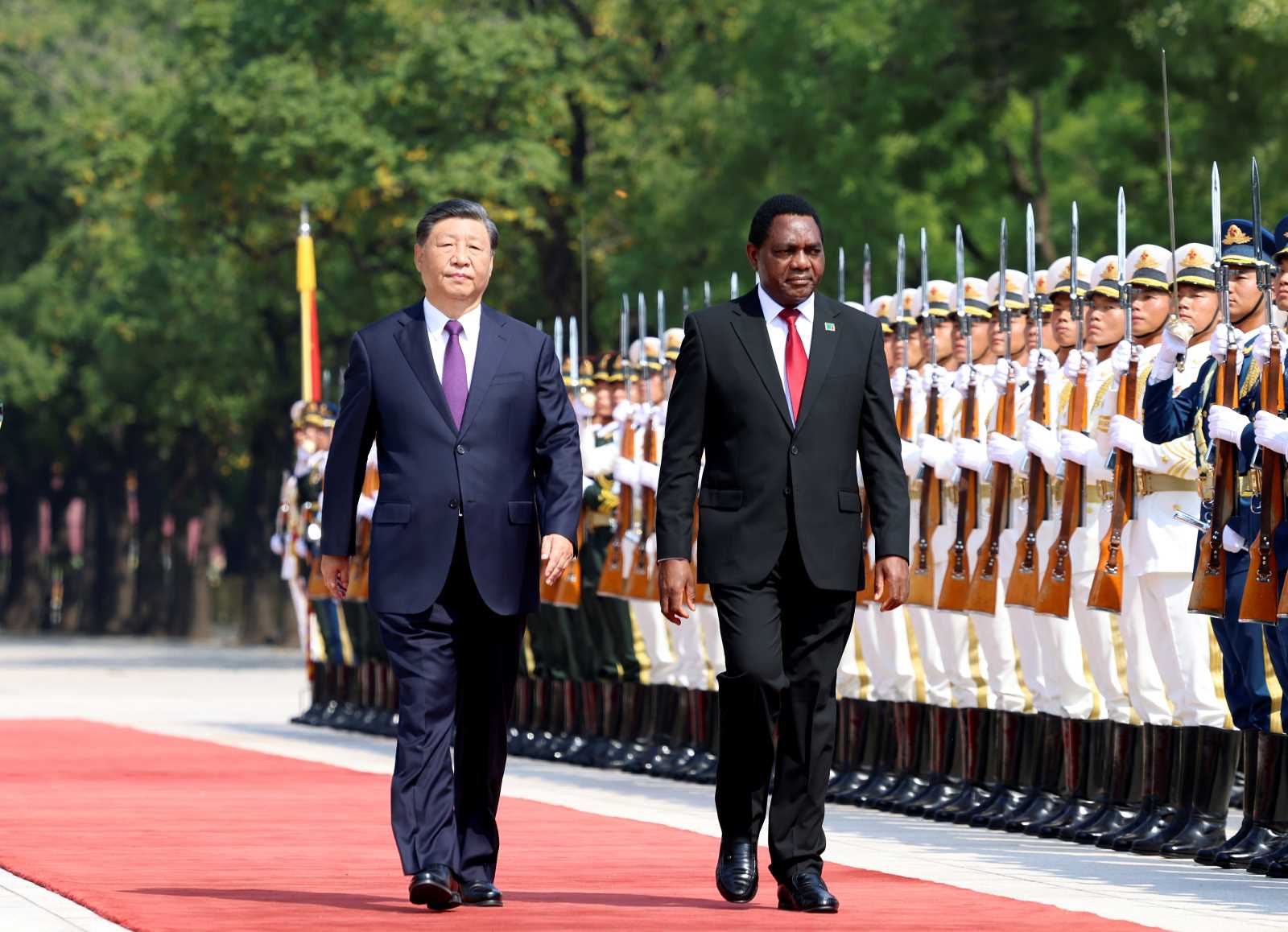

Development finance

Development finance

is the financing of projects, policies and private sector activities that promote social, economic and environmental development. Funds come from public and private, domestic and international sources:

- The largest source of domestic public finance is often taxes. Non-tax revenues include fees, rents and fines, as well as revenues from state-owned enterprises. Another source is domestic borrowing. Examples include the sale of government bonds and securities to domestic banks, pension funds, corporations and the public.

- Domestic private finance encompasses all domestic investment and borrowing by private entities.

- International public finance covers official development assistance (ODA), south-south cooperation (SSC) and foreign borrowing.

- International private finance includes foreign direct investment (FDI) by private companies, portfolio investment, migrants’ remittances to families and friends at home, international borrowing and philanthropic resources.

Climate finance

refers to financing that supports activities to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Instruments include carbon finance, risk insurance, catastrophe bonds, climate resilience funds and debt swaps. In 2009, at the 15th UN Climate Change Conference (COP15) in Copenhagen, industrialised countries committed to collectively mobilising $ 100 billion per year by 2020 for climate action in developing countries. This target was reached in 2022. However, the financing gap for climate action remains significant, amounting to trillions of dollars. In addition, developing countries want international assistance for climate action to be additional to, but not a substitute for, development finance (ODA).

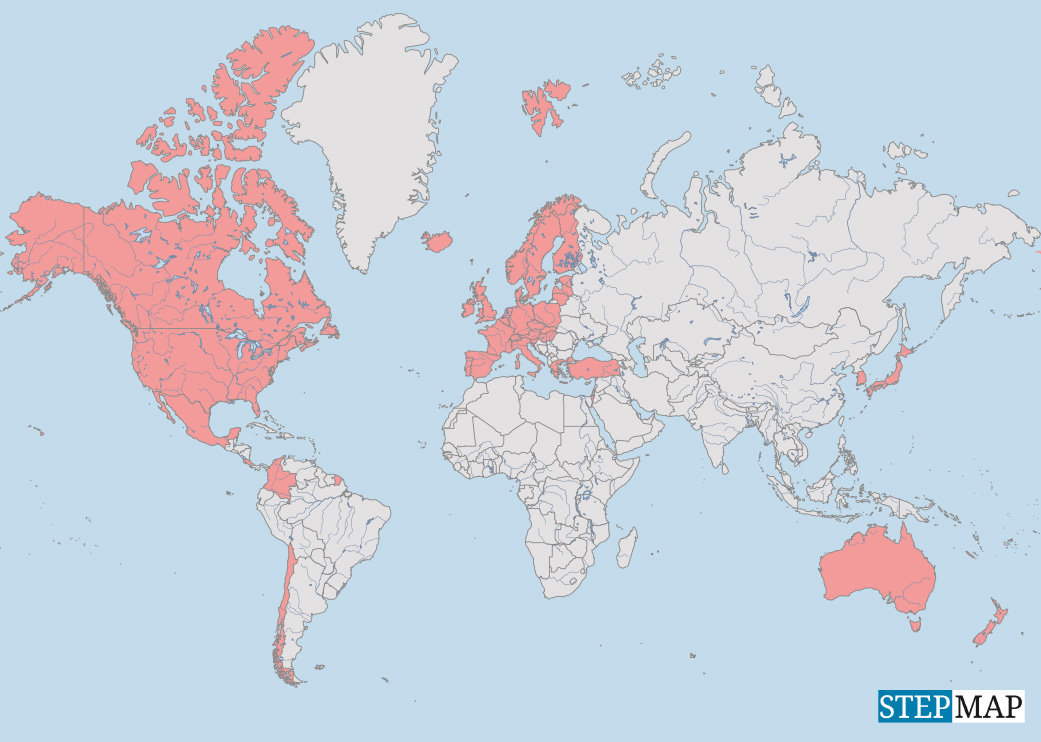

Official development assistance (ODA)

is financial assistance from public donors, including multilateral organisations such as the World Bank, provided to low- and middle-income countries to support development. Development sectors include health, education and infrastructure – but not, for example, the military. ODA consists of either grants or concessional loans, also known as “soft” loans. The latter must contain a grant element of at least 10 % for middle-income countries and 45 % for low-income countries.

ODA is a robust but slowly growing source of development finance, reaching $ 223.3 billion in 2023. At 0.37 % of donor countries’ gross national income (GNI), however, it remains far below the longstanding UN target of 0.7 %. Developing countries have long called for an increase in ODA to meet this target. There have also been concerns that a significant share of ODA has recently been allocated to Ukraine, leading to calls on donors to meet the other UN target of allocating at least 0.2 % of their gross national income (GNI) to the least developed countries.

Domestic resource mobilisation (DRM)

is by far the largest source of development finance. Efforts to increase domestic public resources include broadening the tax base, bringing the informal sector into the formal economy and strengthening tax policy and administration. To increase domestic resources on the private side, it is necessary to develop a domestic financial sector and build a domestic savings base. An enabling environment also needs to be created for investment in sustainable development, for example by improving transparency and implementing good governance, anti-corruption measures and the rule of law. In a globalised world, however, national efforts alone may not fully realise the potential of domestic resource mobilisation. They need to be backed up by international tax cooperation that ensures a fair distribution of taxes among countries and effectively combats tax evasion and avoidance.

Private sector (in development finance)

Private development finance encompasses both domestic and foreign private investment, including both equity and debt. With the exception of remittances, private finance is primarily profit oriented. However, it makes vital contributions to sustainable development. For instance, it creates jobs and increases economic growth and tax revenues – which in turn increase public development finance. The private sector can also invest directly in sectors that are relevant to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as agriculture, industry, technology, infrastructure and energy.

Blended finance

is the practice of using public or philanthropic finance as a catalyst to mobilise private-sector investment for sustainable development. Investments that would otherwise not be viable are made less risky and more attractive through public participation. Blending can take the form of concessional loans, first-loss capital, guarantees, insurance, technical assistance funds and design stage grants. There has been great hope that billions in public funding could leverage trillions in private capital through blending techniques. So far, however, this ambition has remained a dream: Blended finance only mobilised about $ 231 billion in capital for sustainable development in developing countries between 2015 and 2024, with a negligible share going to low-income countries.

International financial architecture (IFA)

is the set of international financial frameworks, rules, institutions and markets that has been put in place to ensure the stability and functioning of the global monetary and financial system. It includes the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the multilateral development banks (MDBs) and financial standard-setters such as the Bank for International Settlements, as well as creditor groups that address sovereign debt issues, such as the Paris Club. Reforming the IFA has been a focus of the financing for development process since 2002. This includes addressing the debt crisis, facilitating greater access to sufficient MDB financing, strengthening the global financial safety net through an inclusive and responsive IMF and improving the fairness and transparency of credit rating agencies.

Multilateral development banks (MDBs)

are international financial institutions set up by a group of countries to provide financing and expert advice in order to promote socio-economic development in low- and middle-income countries. They include the World Bank and regional development banks such as the African Development Bank. MDBs are a major source of concessional finance and have helped to finance projects in key sectors such as health, education and infrastructure. Due to their high credit ratings, MDBs can access capital from the commercial market at significantly lower interest rates than those available to most developing countries. MDB loans tend to have longer time horizons and are more likely to finance riskier projects than private investors. In addition, they provide counter-cyclical support, which means that they provide more financing during crises than they would otherwise. Collectively, the major MDBs disbursed some $ 96 billion in loans in 2022 alone.

Special drawing rights (SDRs)

are an interest-bearing international reserve asset created by the IMF in 1969 to help member countries in times of economic difficulty. The SDR value is based on a basket of five currencies – the dollar, the euro, the Chinese renminbi, the Japanese yen and the British pound sterling. There have only been four general allocations: in 1970-72, 1979-81, 2009 and 2021. In the most recent allocation, the IMF approved a general allocation of about SDR 456 billion, equivalent to $ 650 billion, to increase global liquidity during the Covid-19 pandemic. SDR allocations are distributed in proportion to member countries’ quota shares in the IMF. However, IMF quota shares are so heavily dominated by richer countries that low-income countries have received only about $ 21 billion (3.2 %) of the recent SDR allocations. Nevertheless, even these SDRs proved beneficial to LICs, while many richer countries had no need to use their allocations. To redress the unequal allocation of SDRs, richer countries have channelled or donated more than $ 100 billion of their unused SDRs to developing countries. Any country using its SDRs has to pay interest, albeit at lower rates than those available to developing countries on the commercial market.

Debt distress and debt insolvency

Borrowing is an important way for governments to finance investments in growth and development. However, it is also important for them to ensure that they can continue to service their debt – that is, to maintain a sustainable debt burden. A country is said to be in debt distress when it faces difficulties in meeting its debt obligations. Indicators include missed payments or arrears. If the situation deteriorates, a country enters debt insolvency: It cannot meet its obligations even with policy adjustments. Unlike debt distress, where repayment is still possible with external support, debt insolvency suggests that debt relief or restructuring is inevitable. According to the International Monetary Fund, by 2024, more than 50 % of low-income countries were either at high risk of debt distress or already in debt distress, with 25 % of middle-income countries also being at high risk.

Links

United Nations Resident Coordinator Office in Turkey, 2021: Development finance glossary.

turkiye.un.org/en/215399-development-finance-glossary

UN, 2025: FfD4 Outcome document – Zero draft.

https://financing.desa.un.org/document/ffd4-outcome-document-zero-draft

Yabibal M. Walle is a senior researcher at the German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS).

yabibal.walle@idos-research.de