Shared prosperity

“The middle class is missing’’

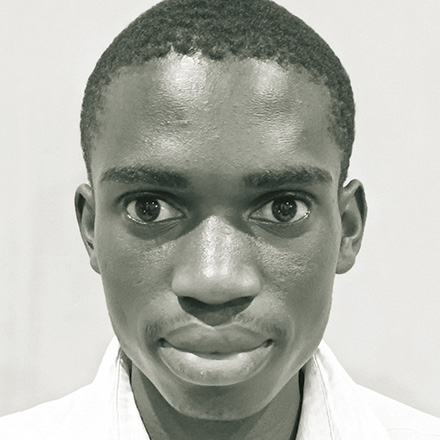

James is married and has two children who are both in private school. The family owns a car. James is a Malawian who could be considered middle class. He is well educated and works as a lecturer at a college in the city of Blantyre. He finds things tough nonetheless. “It is survival of the fittest,” he says. “Life is proving to be so expensive, and one needs to be creative in order to find an extra penny to make ends meet.”

James does not only rely on what he earns teaching at the college, which is not enough to provide for his family and pay for his children’s education: “I do other things in order to meet my expenses such as school fees, rent, car maintenance and other costs.” He therefore also does work as a media consultant.

While there are no precise statistics on the country’s middle class, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reckoned in 2017 that 50.7 % of the population lived below the poverty line and 25 % even suffered extreme poverty. The small number of Malawians who fit the middle-class profile are usually found in the country’s three main cities: Blantyre, Lilongwe and Mzuzu and tend to work in government, finance, business and marketing.

Nonetheless, Betcheni Tchereni, an associate professor of economics at the University of Malawi, does not see much evidence of a middle class in Malawi. A lot of people are struggling to make ends meet he says, unemployment is very high, and a real middle class is “missing”. He admits that some people are relatively well off, but adds: “If we are to compare them to the middle class of other parts of the world, we are nowhere near a middle class.” He says the people he is thinking of in Malawi tend to be “deep in debt”, struggle to send their children to good schools and often cannot afford decent housing.

Low-income country

According to World Bank definitions, lower middle-income economies have a GDP per capita above $ 1000. The most recent World Bank figure for Malawi is around $ 600, so it is a low-income country.

Malawi is stuck in slow growth which is compounded by the unequal distribution of wealth and incomes. The challenge of reducing social disparities is huge. A history of corrupt public institutions has made matters worse.

In 2015, an Oxfam report stated the gap between the richest 10 % of Malawians and the poorest 40 % increased by almost a third in the years 2004 to 2011. Reasons indicated by Oxfam included a huge sovereign debt burden, a small tax base and distrusting international development partners who spent aid outside the government system. For these reasons, the government struggled to mobilise resources.

In the meantime, the courts have begun to improve governance. Most prominently, the Supreme Court annulled a manipulated presidential election. The new president, Lazarus Chakwera, has a reputation of integrity, but he has not been able to make a difference in economic affairs so far (see Rolf Drescher on www.dandc.eu).

He was inaugurated in the summer of 2020, and one of the big challenges he faces is that the Covid-19 crisis has made matters worse in Malawi. That is true in many other developing countries too (see Ronald Ssegujja Ssekandi on www.dandc.eu). Poverty has been spreading, especially in urban areas.

Stuck in informal economic activity

The big problems predate Covid-19, however. The full truth is that most Malawians work in the informal sector, which includes smallholder farms. According to a 2013 Malawi Labour Force Survey, 89 % were engaged in precarious employment. As is true of many African countries, Malawi needs a development model “that generates employment in the formal sector and provides a measure of income security to all”, as Ndongo Samba Sylla put iton www.dandc.eu.

Informal-sector businesses are marked by low productivity, low incomes and no social protection. Whether the businesses are involved in agriculture, manufacturing or retail services, hardly matters. Even though it is not taxed, informal activity is a recipe for poverty.

Joshua Mkandawire is a person concerned. He is 32 years old and runs a small barbershop in a low-income neighbourhood of Mzuzu. He has a wife and three children. “It’s not easy,” he says, “I do not make enough, but I’m grateful because this is better than nothing.”

His wife Catherine spends most of her days selling vegetables on the streets to make some extra money. Housing costs and the rent for the barbershop, she says, are draining her husband’s income.

Scholar Tchereni considers that government needs to create a more fertile environment for formalised manufacturing industries, while at the same time making sure that labour laws are adhered to. “Most people are being paid below the minimum wage, we need people to be paid handsomely,” he says (also see Ruud Bronkhorst on www.dandc.eu).

“We also need to have a lot of entrepreneurs in the country in order to reduce the income inequality gap. At the moment we have a lot of traders and not entrepreneurs.” According to Tchereni, a progressive taxation would help to distribute income from the rich to the poor.

Rabson Kondowe is a freelance journalist based in Blantyre in southern Malawi.

kondowerabie@gmail.com