Food habits

Popular street food in Uganda

Chapatis are a type of traditional Indian flatbread made from whole wheat flour. There is no clear narrative of how making chapatis became popular in Uganda. In part however, it could be attributed to the Indian migrants who have lived in Uganda since the colonial era, around the turn of the 19th century.

Popularly made as a street food, the chapati is enjoyed by almost all Ugandans – rich and poor. However, among the low-income earners, and especially those in the poor neighbourhoods, the chapati has taken a distinct identity as a staple food. It is enjoyed in several ways; as a plain snack, as a full meal served with a soup of beans “Kikomando”, or as a “rolex”, combined with an egg omelette. It is highly bulky and gets people feeling satisfied for longer periods of time.

As such, it is popular among groups such as students, labourers at construction sites, hawkers of goods and those living in ghetto areas in urban centres.

Chapati making and selling is big business. Uganda’s informal sector is made up of many who ploy this trade. To start a chapati business, one needs a wooden stall covered by an umbrella for shade on the street, a charcoal stove and basic food such as cooking oil and wheat flour. With about $100 or less, one can start a fully-fledged business. Many such chapati stalls are popular on Ugandan roads.

Chapatis have made advantages as a food source. Being made from whole wheat, they are a good source of dietary fibre, promoting digestive health. However, the chapati is made differently in Uganda and given the excessive use of cooking oils and sometimes unrefined wheat, they can be a danger to health, causing constipation and so on.

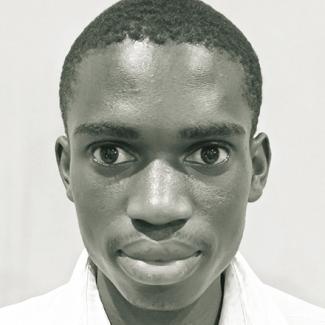

Doing business as a chapati vendor can be profitable. Wanyara Ivan, a young man who runs a chapati stall in one of Kampala’s suburbs earns around 80,000 Ugandan shilling (about $ 21) per day. He says he has been able to meet his family needs like food, water and house rent.

But the business has challenges. There is stiff competition. It is common to find chapati stalls within a few metres from each other on one street. Keeping hygiene can be difficult. Working in open spaces, the wind can blow dust and other dirt into the chapatis-putting customers at the risk of food poisoning. It is worse if the chapati maker is not cautious of their hygiene, such as washing hands with soap and cleaning the cooking pans well.

Chapati vendors also face difficulties with the law. Street vending is illegal in Kampala and many towns. As such, these vendors either must pay bribes to law enforcement officers, or risk arrest and confiscation of their property. City authorities urge them to move into regular shops – something that would make business expensive and unaffordable for the poor.

Other global factors matter too. Ukraine is an important source of wheat and cooking oil. Given the ongoing Russian war of aggression in Ukraine, the price of wheat and cooking oil has gone up in Uganda. Amidst difficulty, chapati vendors have had to increase their prices, or reduce the size of the chapati to the disgust of their largely poor clientele.

Mathias Galabuzi is a student of Journalism and Communication at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda.

galabuzimathias@gmail.com