Economics

Growth, green growth or degrowth?

UN Secretary-General António Guterres has coined the phrase of the boiling planet. Extreme weather events around the world show that humankind is indeed on a disastrous course. The erosion of biodiversity, increasing amounts of plastic waste and desertification point in the same direction. The way we run national economies must change.

In political discourse, the terms green growth and degrowth have become popular. Unfortunately, they are not well defined. They are thus only of limited analytical use. As a matter of fact, even conventional GDP growth, which is generally considered a measurement of economics of success, is not the precise indicator that its seemingly exact numbers make many people believe. The obsession with GDP is excessive – and a bit absurd.

The term green growth is a modified version of the GDP-growth paradigm: It suggests that business can go on pretty much as usual as long as some environmental damages are reduced or, perhaps, eliminated. The problem is that:

- we must tackle several kinds of ecological hazards,

- there are many ways to deal with them, but

- in many cases, supposed solutions trigger follow up problems and/or interact poorly with solutions for other problems.

In business life, however, corporate leaders love to claim that they are investing in green growth simply because they are tackling this or that problem. Different corporate strategies do not add up to any coherent approach to the global environmental crisis.

The meaning of “sustainable development”

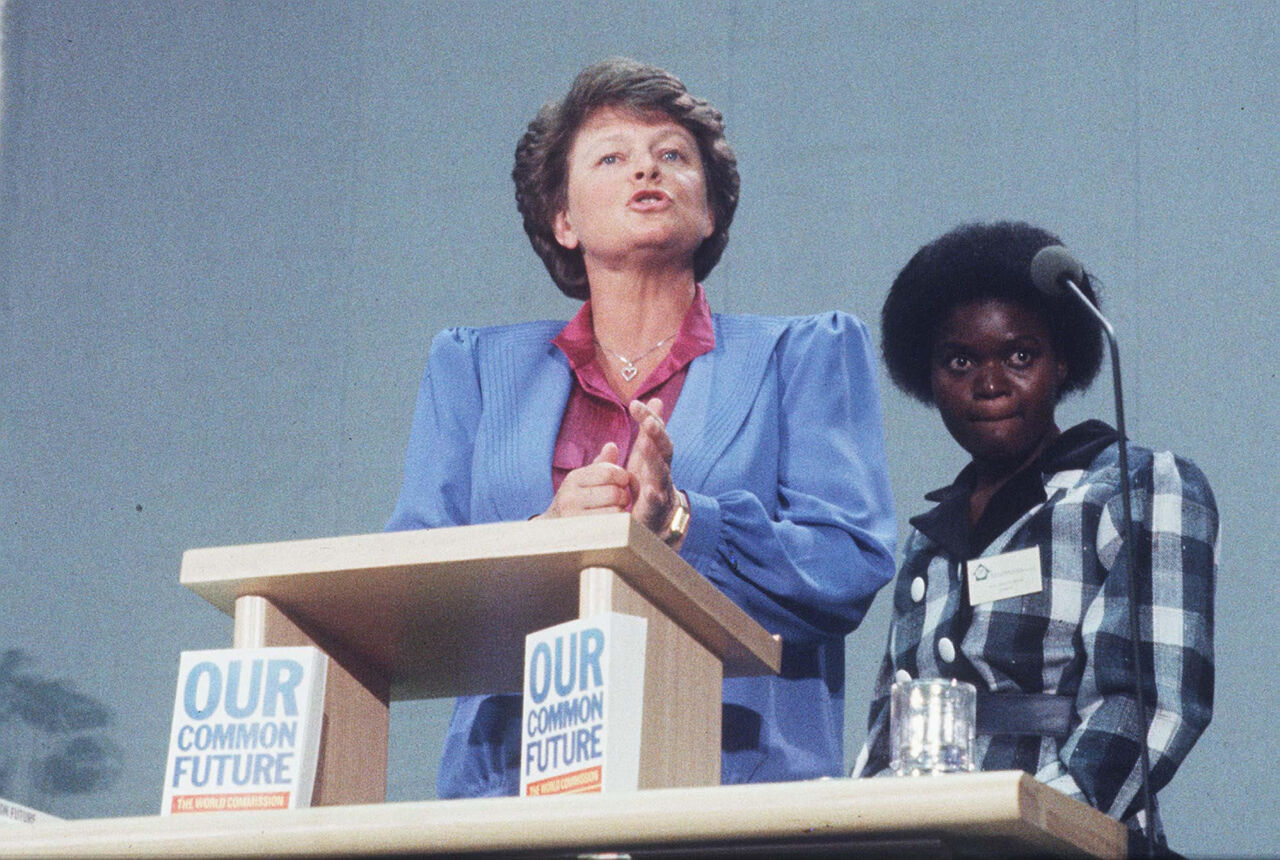

Many people mistakenly believe that green growth is a synonym for “sustainable development”. While it is true that, when applied to practical purposes, the latter term too is a somewhat cloudy concept, it is at least conceptually clearer. Almost four decades ago, it was defined as a trajectory that “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” in the paradigm shifting UN report “Our common future”.

The report was published in 1987 by the World Commission on Environment and Development, which was led by Gro Harlem Brundtland. The definition is global in nature because the Commission insisted that the needs of the world’s poor were currently not met and had to be prioritised. That is obviously still the case today.

Moreover, the Commission appreciated that there are environmental limits to what human beings may do. Unlike green growth, sustainable development does not suggest that people are entitled to ever increasing amounts of whatever they might desire. The sad truth is that all environmental crises that were evident in 1987 have only escalated since.

Some environmentalists now call for degrowth. Put simply, they want to shrink national economies, arguing that this is the only way to protect the planet’s health. What they miss is that degrowth is not a strategy that will help humankind meet the needs of the global poor. Per-capita GDP is too low for any significant redistribution to do the job in countries with low incomes and lower-middle incomes. This is not to suggest that, given huge inequities of assets, incomes and opportunities, there are no prospects for redistribution at all; but discussing them is beyond the scope of this short essay. These nations certainly need growth to develop sustainably, nonetheless.

Things are different in countries with upper-middle and high incomes where redistribution, too a large extent, has indeed eliminated absolute poverty (which means a person has just enough to subsist), though, in many countries, relative poverty is growing (which means a growing share of people are falling far behind their nation’s average income).

The degrowth proponents have a point when it comes to consumption. The average lifestyles of high-income nations are not sustainable. They cause too much waste and emissions, claiming a disproportionate share of the global commons. UNICEF has estimated that humankind would need three Earths rather than only one if all countries were to enjoy Germany’s level of resource consumption.

Building clean infrastructure means growth

Nonetheless, it is a fallacy to believe that simply shrinking economies would protect the environment. The reason is that high-income countries must build new, sustainable infrastructures. Phasing out fossil fuels is impossible without massive investments in clean energy. Decarbonising transport systems or the building sector must also be underpinned by massive spending. That kind of expenditure invariably means GDP growth.

It must happen fast, moreover, for at least two reasons:

- heavily polluting economies must be made eco-friendly, and

- low-income countries need tested models to build clean infrastructure.

As argued above, least-developed countries need growth to eliminate poverty. However, the global environmental crisis has escalated to such a point that they must avoid building infrastructure that will inevitably cause continuous environmental harm in the future.

For humankind to have a liveable future on a small planet, all governments must focus on sustainability. To what extent achieving sustainability goes along with growth or not, is only of minor relevance. It goes without saying, of course, that those governments whose countries have the strongest capacities and have also contributed most to the global environmental crisis bear the greatest responsibility. Emerging markets – and especially those that are fast catching up with advanced nations – must act too.

Praveen Jha is a professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi.

praveenjha2005@gmail.com