Our view

History did not end

The present is the result of the past. History shapes how societies live today.

In one part of the world, a series of technological innovations fostered prosperity, but also made wars more brutal. Countries with high incomes learned some lessons in World War II and were able to enjoy several decades of stability and democracy. Some even spoke of an “end of history”. Henceforth, they claimed, reason and multilateral cooperation would facilitate good lives all over the world.

That was then. History did not end, as new wars, the dramatic escalation of the climate crisis and the growing presence of anti-democratic forces in parliaments and even governments of high-income countries show.

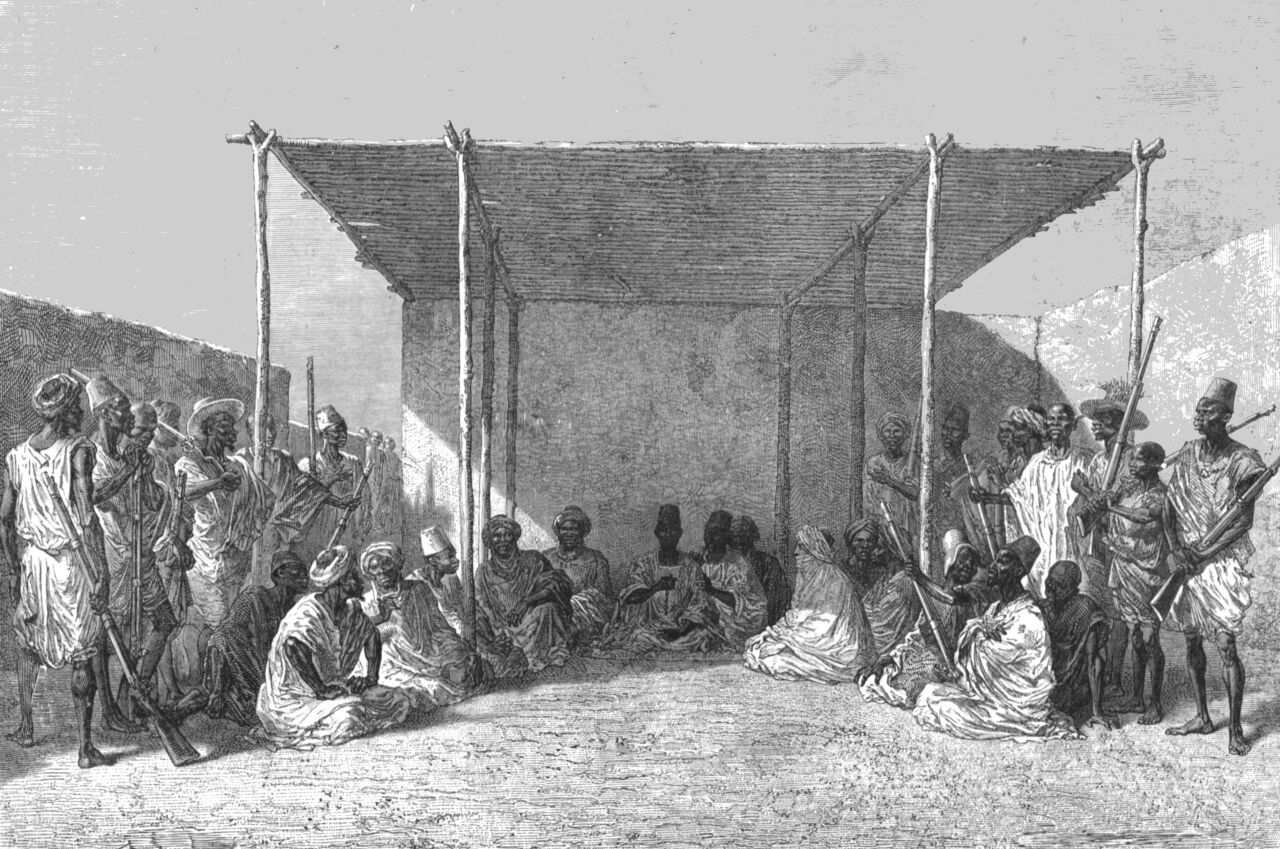

In less privileged world regions, people have known for a long time that the present is not the happy conclusion of past experience. Their past was different. Colonial oppression, exploitation and lack of freedom have marked the history of Africa, Latin America and Asia, in many cases only ending in the 20th century.

The past of former colonies and imperial powers is intricately linked, of course, and so is the present. The prosperity of the latter was, to a large extent, built on the exploitation of the former.

Imperialist Europeans conquered large parts of the world. Even the USA is the result of colonial ambitions – and of the brutal subjugation and even extermination of indigenous people. Many Americans love to forget this history.

Similarly ignored, however, is the fact that not only western powers built huge empires. Indeed, Russian imperialism is still aggressive, as the invasion of Ukraine proves. The Osman Empire was a Muslim colonial power. And slaves were not only traded across the Atlantic, but towards Arab destinations too.

Missed opportunities

Colonial masters always assumed to know more, be more advanced and have greater relevance than any subjected people. Imperial powers systematically missed opportunities to learn from knowledge and cultural practices, many of which had been passed down for centuries.

Blatant grievances today are often traceable to the abusive attitudes of colonists. In Brazil as in the USA, legacies of colonial rule include excessive social disparities, structural racism and the reckless exploitation of natural resources.

Hasty and incomplete decolonisation, moreover, is at the root of many sovereign debt crises that haunt countries with low and middle incomes. At home, colonial powers had a propensity to reduce corruption, build comparatively clean administrations and enforce the rule of law. In the colonies, by contrast, they relied on cronyism and bribes, showing hardly any interest in universal legal standards that applied to everyone.

All too often, approaches to governance did not change after independence. Officeholders hardly worried about government debt, but many are happy to cozy up to foreign powers provided they personally benefit.

Bassirou Diomaye Faye, Senegal’s left-leaning young president, who was elected this year, is among those who speak up for the need of a “second liberation”. They see that not all, though many of today’s grievances result from the action of white people.

Former colonial powers bear a responsibility for former colonies. They do not do it justice if they:

- focus merely on cheap access to commodities,

- leave former colonies to cope on their own with huge debt burdens or the rising costs of climate damages (which, of course, low-income countries contributed little to cause),

- fail to return cultural artefacts and mortal remains to the communities concerned, or

- refuse to even consider reparations for atrocious crimes of the past.

Critics argue that colonial attitudes persist in the development policies of nations with high average incomes. As the condescending rhetoric of “donors” and “recipients” shows, they have a point.

All too often, the policies of donor governments reinforce dependencies and block true cooperation. True cooperation happens at eye level, and it requires rules that do not only entrench the power of the mighty, but actually work for everyone.

Katharina Wilhelm Otieno belongs to the editorial team of D+C/E+Z.

euz.editor@dandc.eu