Technology

How AI exploits

In Kenya, thousands lined up two years ago to receive free crypto tokens from Worldcoin, a project co-founded by US tech entrepreneur and OpenAI CEO Sam Altman. In exchange, they had to consent to an iris scan. The Kenyan government eventually halted the practice.

In the same country, Ladi Anzaki Olubunmi, a Nigerian content moderator (see box) for TikTok, was found dead in her apartment. Reports suggested that she had been repeatedly denied leave requests, though Teleperformance – the subcontractor handling TikTok’s content moderation – dismissed these claims as false.

Meanwhile, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, miners extract rare earth minerals under dangerous conditions. Many work in illegal cobalt mines, exposed to toxic chemicals without any protective gear – some of them are children.

What they have in common is that they are part of the supply chain of AI in Africa.

A supply chain can be described as the sequence associated with the manufacturing and delivery of a product or service to consumers. Typically, this involves the role of raw materials, manufacturing and production, and, at the end, distribution and sales, as well as the services associated with the end product. However, when we talk about the supply chain for AI technologies (such as large language models, algorithms or self-driving cars), we neglect the connections that go beyond the collection and analysis of data. We ignore the interconnected stages of AI development, which range from the extraction of the raw materials needed for hardware to the provision of the technology and its use.

Africa remains a continent where labour markets are characterised by informality; 83 % of the workers are employed in the informal sector, according to the International Labour Organization. In the case of the supply chain for AI, the existence of precarious, informal, or exploited labour is rarely explicitly mentioned. This highlights an idealised understanding of how a supply chain works in practice. This is not new or unique to AI – this type of labour is generally seldom visible or problematised.

We need a clear understanding of the specific challenges faced by labourers along the AI supply chain and an explicit examination of how AI systems depend on human exploitation. Beyond exposing injustices, it is essential to support worker-led movements already fighting for fairer conditions here.

Exploitative dimensions

The fact that the exploitative dimensions of the AI supply chain are being ignored reflects a general lack of information about informal, precarious or abusive working conditions, for example in the following contexts:

- mineral extraction for AI hardware, often carried out by workers in dangerous, unregulated conditions,

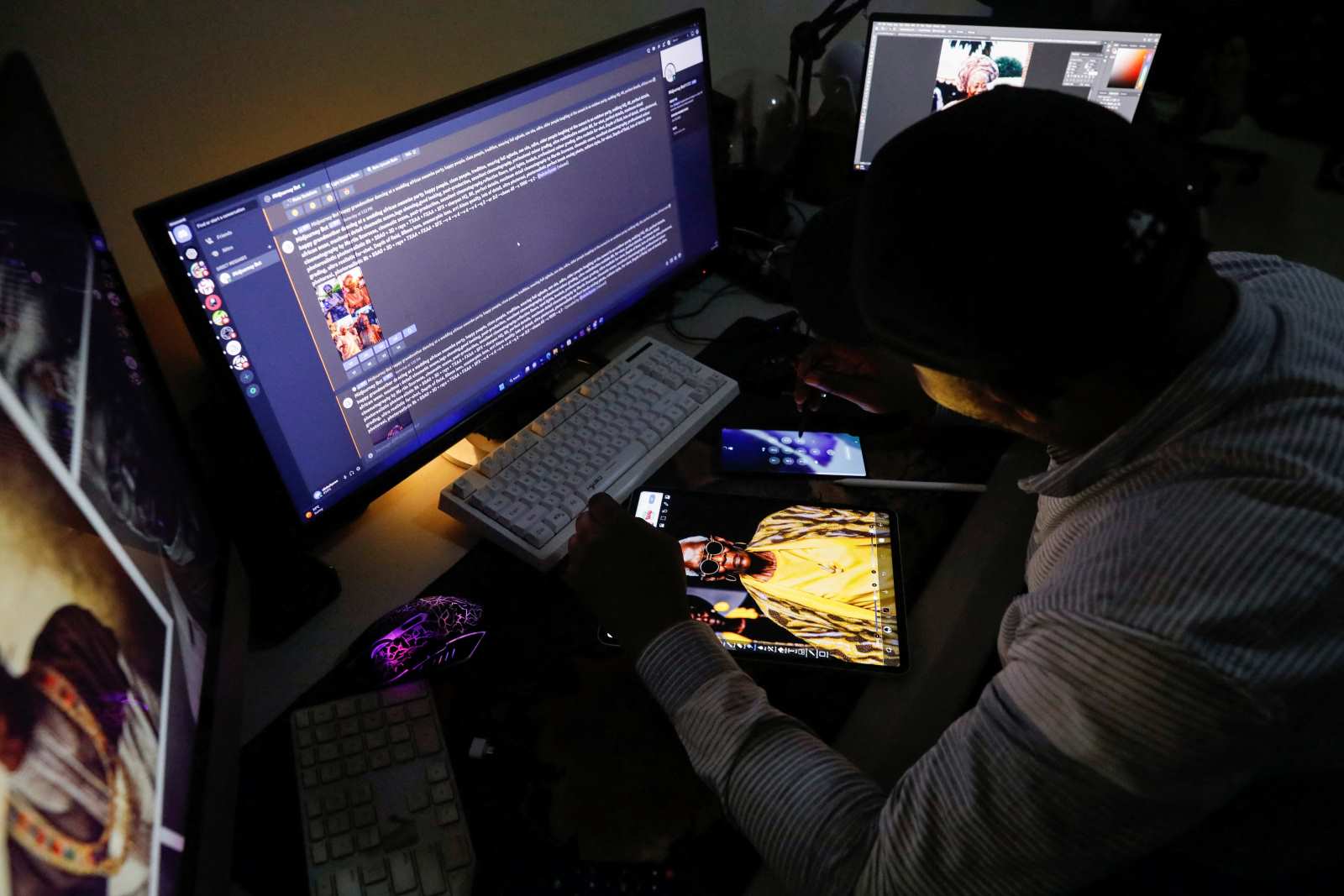

- content moderation, outsourced to precariously employed workers who endure psychological strain with little support,

- data capture, where private information is collected and monetised without adequate consent or protection, and

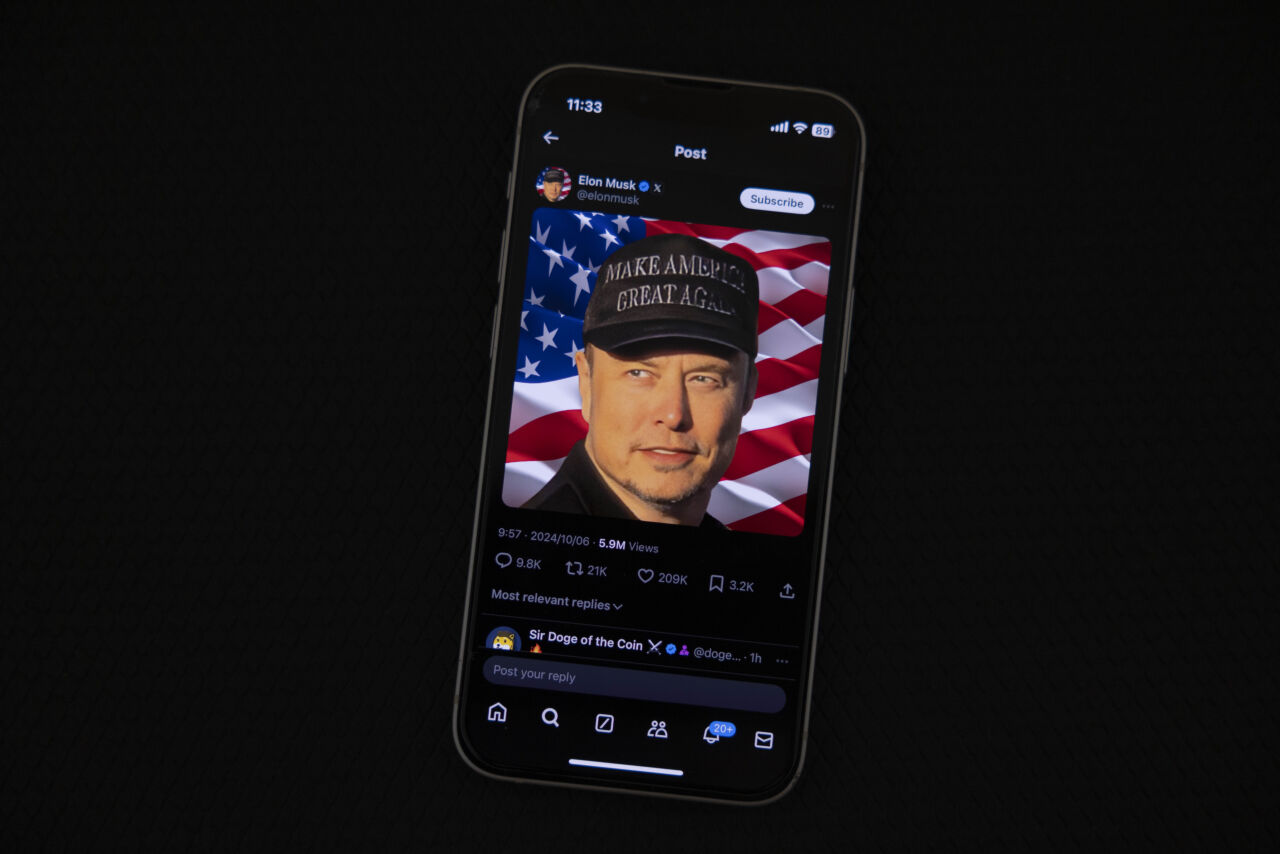

- platform economies, for example ride-hailing platforms like Uber and Bolt, where drivers are subject to opaque algorithms and unstable earnings.

AI is often portrayed as a tool for progress, and countless reports praise its benefits without critically examining its impact on the environment and livelihoods, or its role in deepening inequalities and eroding social contracts. This uncritical optimism masks the real costs of AI-driven systems, diverting attention from the precarious labour and systemic injustices that sustain them.

The reality is that AI supply chains do not serve the interests of vulnerable workers. Instead, they are designed to meet the demands of capital, with little regard for social cohesion, economic fairness or environmental sustainability. The relentless pursuit of profit – without safeguards for the deployment of new technologies – has not only exacerbated existing social injustices but has also introduced new forms of exploitation and harm.

The rapid expansion of digitalisation is reshaping labour and society worldwide. As labour movements lose momentum, we must ask ourselves how workers in AI development supply chains can be supported to benefit from better working conditions, fair wages and reliable insurance. Without systemic change and stronger protection, the risks for workers will become even greater in the future, especially on the African continent.

Mobilisation and legislation

Three key channels can help defend labour rights in the AI supply chain: mobilisation, enforcement of existing laws and new legislation.

Social mobilisation remains a powerful tool in Africa. However, as workers take action against poor conditions, they need support from state institutions that prioritise labour rights over corporate interests.

While AI itself is rarely addressed in African labour laws, existing legislation across the continent already recognises the importance of workers’ rights – for example, in the 2019 Abidjan Declaration. However, one thing is a declaration, and another is holding companies and states to account. African countries need to improve their accountability mechanisms to enforce the labour laws that already exist.

In addition, governments must establish clear mandates to:

- build state capacity to assess and understand the impact of AI on their populations,

- regulate data rights and privacy, ensuring that citizens’ information is protected and that companies uphold their responsibilities,

- adapt labour laws to account for emerging forms of work, safeguarding service providers who rely on AI-powered platforms or tools for their livelihoods.

AI represents a new avenue of exploitation for Africa, where much of the workforce already operates under precarious conditions. As technology advances, it is crucial to prioritise workers’ rights and well-being through mobilisation, stronger labour movements and the formation of unions. Existing labour laws must be reformed to address the realities of AI-driven work, while new regulations are needed to safeguard workers across all sectors. Without such measures, companies will continue to evade accountability, for example through outsourcing on the continent, and AI will only deepen existing inequalities instead of fostering inclusive development.

Fabio Andrés Díaz Pabón is a research fellow on Sustainable Development and the African 2063 agenda, hosted by the African Centre of Excellence for Inequality Research (ACEIR) of the University of Cape Town.

fabioandres.diazpabon@uct.ac.za

Azza Mustafa Babikir Ahmed is a research fellow on Sustainable Development and the African 2063 agenda, hosted by the Institute for Humanities in Africa (HUMA) of the University of Cape Town.

azza.ahmed@uct.ac.za