Identity politics

Why the acronym BIPoC does not have to explain anything

“BIPoC” and the older term „PoC“ are acronyms that in the past were frequently used incorrectly and vaguely – especially by white people. Thus, it is important to first acknowledge that this text is a response to Hans Dembowski’s contribution on this topic (E+Z/D+C Digital Monthly 2024/03, p. 9), and that therefore two white people are discussing the term.

This situation is contradictory because the acronyms were not created for use by white people, as this text will make clear. Its main goal, however, is to offer an analytical perspective on the underlying concepts, even though doing so will not resolve the aforementioned contradiction.

In the nineteenth century, the term “(free) people of colour” referred to freed slaves in the USA. Similarly, people in French Caribbean colonies who had one European and one African parent and thus greater social influence were called “gens de couleur libres”.

In 1963, Martin Luther King Jr used the term “citizens of colour”. It became important in the American civil-rights movement, particularly as a reclamation of the derogatory term “coloured”, which in the USA during the period of racial segregation referred to places such as hotels, waiting rooms or schools where African Americans had to go separately from the white population.

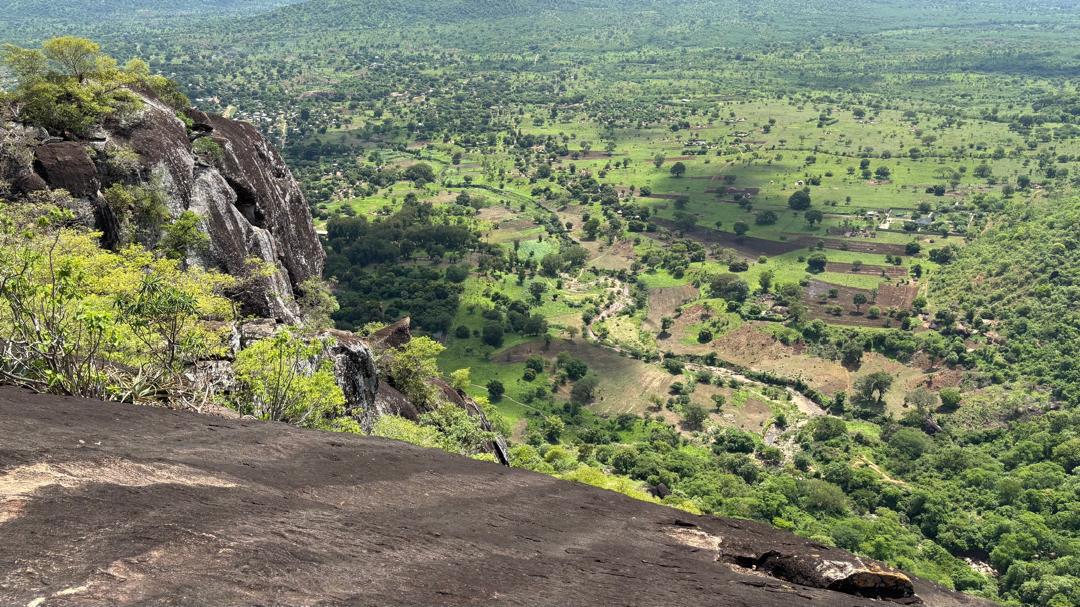

Figures like Che Guevara, Patrice Lumumba or Kwame Nkrumah

Since then, PoC has referred to an alliance of various communities that have experienced structural racism and want to create solidarity through this self-designation. This understanding is inspired, among other things, by the spirit of international solidarity of the 1960s, carried by central figures such as Che Guevara, Patrice Lumumba and Kwame Nkrumah – and in the USA, above all, by the Black Panther Party.

The term PoC is thus meant to counter racist structures that divide society and emphasise differences. It emerged when marginalised groups asserted and organised themselves and began to work together politically.

“People of Colour” and “immigrant background”

The term first caught on in the USA, but is now being used elsewhere, too. In Europe, it is primarily used to focus on the experience of racism – and not, for example, on the experience of immigration. Thus, it makes a distinction from designations like “immigrant background”. The political scientist Kien Nghi Ha speaks of a “people of colour approach” that aims to promote antiracism from an identity politics standpoint and thereby recognises the variety of affiliations each person has.

The goal, therefore, is not to classify certain people. Moreover, the term should in no way make it easier for white society to create external labels and categorise marginalised people. It emerged as a response to a white, racialised view of all “others” and the atrocities that view has engendered. This means that the specifics of skin colour and ancestry within the marginalised spectrum play no primary role. Instead, as Kien Nghi Ha correctly states, the term is an overarching self-designation used by the people in question.

This basic idea of the “people of colour approach” emphasises mutual solidarity rather than the different experiences that subsumed groups have had and continue to have with racism. The addition of “Black and Indigenous”, which turned the acronym into the prevailing and much-discussed “BIPoC”, attempts to make certain groups within the approach more visible and call attention to them in speech. The concern was that these groups were getting lost in the term “people of colour”, though they are central to solidarity efforts given the severity of their experiences with racism. It is unclear when exactly this addition occurred. The New York Times has traced its first appearance on X (formerly Twitter) back to 2013.

Criticism of the term BIPoC

Hans Dembowski argues that the term is of little use for a variety of reasons, especially in world regions like South Asia and Africa, where other identities are more important. He writes, correctly, that the entire concept has become controversial “because not every person who belongs to a minority wants to be lumped into one big category to form an opposite to white people”.

However, a major reason why parts of marginalised groups reject the term BIPoC is that many white people use it incorrectly or misuse it. Damon Young, a Black American writer, notes in an essay that “PoC” on the one hand has become an alternative for white people who do not feel comfortable simply saying “Black”.

On the other hand, he writes, in the USA the term has become an end in itself: when companies and individuals say “PoC”, they feel that they have adequately proven their antiracism and no longer have to deal with the issue. Because of this usage, Young believes that the term has lost its original meaning and degenerated into a linguistic gesture.

In-groups and out-groups

American feminist Loretta Ross made a similar argument in 2011 in what has become a frequently cited YouTube video in which she discusses the term “women of colour”. According to her, white people have used the term in such an inflationary way that it has lost its original political meaning. Ross says that many people now believe that whites invented it. In the video, she explains: “This is a term that has a lot of power for us. But we’ve done a poor-ass job of communicating that history so that people understand that power.”

What has happened to the term BIPoC is typical of language we use to talk about (political) oppression based on identity, among other things, as publicist Constance Grady writes in a story on Vox in which she takes a linguistic look at the acronym. An in-group develops a self-designation to talk about the experiences that the members of that group share. When the term catches on, out-groups begin using it vaguely, thereby robbing it of its political power.

As Grady rightly observes, the out-groups are not necessarily trying to do harm. In the case of “BIPoC”, they are often instead trying to use the right words – but without really thinking about their meaning.

No “oppression Olympics”

The protagonist of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s brilliant novel “Americanah” writes in her fictional blog that an “oppression Olympics” is taking place in America: various minorities “all get shit from white folks, different kinds of shit, but shit still. Each secretly believes that it gets the worst shit.” Adichie’s protagonist believes this proves that there is no “United League of the Oppressed”.

Yet to put it bluntly, this is precisely the starting point for the terms BIPoC and PoC. The approach stems from the desire to give centuries of racial oppression a common standpoint, without creating a hierarchy of that oppression.

The fact that, at the same time, people from various groups want to be named and not disappear behind an acronym is both legitimate and understandable. It is equally understandable that people from the actual in-group of the term BIPoC can no longer identify with it, since white society in particular has been misusing it as an out-group: partly as an empty, supposedly anti-racist gesture; partly in the expectation that it should explain complex identities – which it certainly cannot do, and for which it was not created.

However, this does not call into question the legitimacy of the acronym itself. The initial idea of solidarity behind the abbreviation remains valid. If it serves as a marker of similar experiences and can create solidarity among a very large part of humanity, it still has the potential to be a very powerful concept.

Katharina Wilhelm Otieno belongs to the editorial team of D+C/E+Z.

euz.editor@dandc.eu