Pharmaceuticals

Brief history of ARV treatment in South Africa

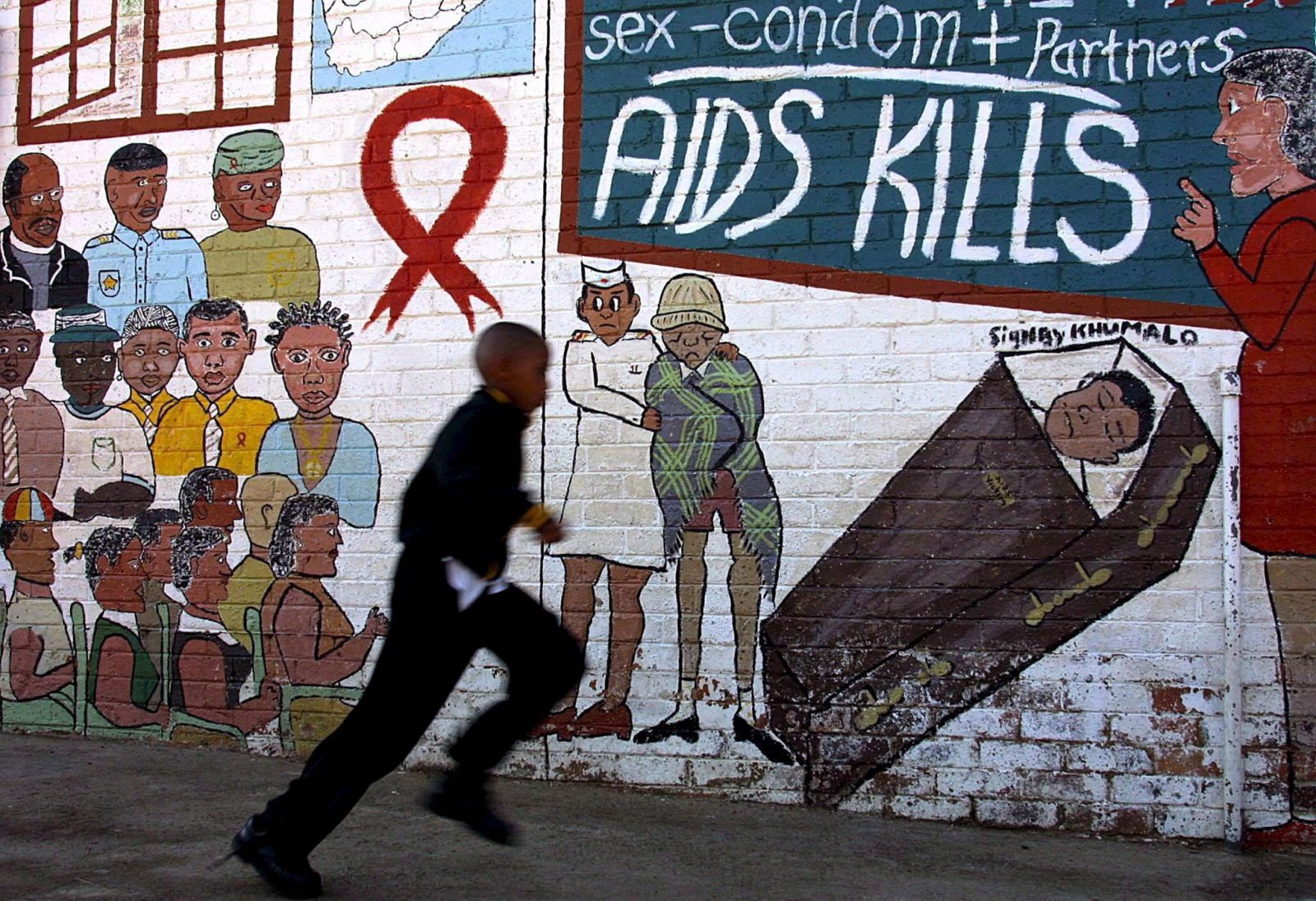

Quite evidently, poverty, lack of education and traditional attitudes mattered very much. For a long time, however, South Africa’s government – then led by President Thabo Mbeki – stayed in denial, failing to launch the kind of science-based awareness campaigns that might have helped to motivate people to practice safe sex, especially by using condoms. By the time those campaigns started, more than a third of pregnant women that took prenatal care were testing positive.

Dreadful death sentence

When HIV/AIDS first started to make headlines internationally in the early 1980s, a positive HIV diagnosis was like a dreadful death sentence. There was no therapy, so patients’ health would slowly deteriorate due to an increasing number of infections one of which would eventually prove fatal.

That pattern changed in the late 1980s, when scholars developed anti-retroviral medications (ARVs). ARVs do not heal HIV, but they suppress its consequences. For those who could afford ARVs, HIV thus became a manageable chronic disease. In was no longer deadly. The innovative pharmaceuticals were expensive, however, and protected by patents. In many high-income countries, governmental health services covered the costs.

Due to the prices, however, ARVs largely stayed unavailable where they were needed most – in developing countries and emerging markets hit by the pandemic. South Africa was a prime example, but other African countries were affected too.

Looser intellectual property rights

Things began to change after the Doha summit of the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2001. Due to pressure from international civil-society groups and countries like Brazil and Thailand, where governments accepted the medical science and were determined to stem the health crisis, the WHO made intellectual property rights more flexible. Governments were given the right to grant compulsory production licences should any pharmaceuticals be unaffordable, but indispensable for public health. From then on, multinational pharma companies began supplying ARVs to low- and middle-income countries at much lower costs, making ARV therapy feasible there.

From 2004 on, ARV treatment was rolled out in South Africa. In retrospect, it was a great success. Nonetheless, more still needs to happen.

Hans Dembowski is the editor in chief of D+C/E+Z.

euz.editor@dandc.eu