Multilateral affairs

Brief history of WTO flexibility regarding pharma patents

In that setting, governments in some emerging-market countries allowed generic production in spite of World Trade Organization (WTO) rules on intellectual property (IP). Treatment costs fell in those countries, and health-care outcomes improved in Brazil and Thailand, for example. Civil society organisation took note and supported these and other governments’ efforts for change.

Then in 2001, the WTO summit in Doha modified the global IP regime substantially. Facing a public health crisis, every country has since been entitled to grant compulsory licences to companies to produce generics of patent-protected pharmaceuticals. WTO rules even allow them to grant such licences to companies in foreign countries and import those drugs.

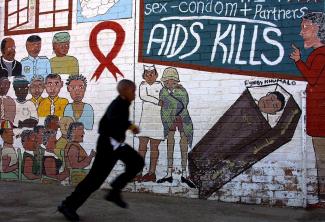

After Doha, affordable treatment fast became available in southern Africa and other world regions severely affected by HIV/Aids. The main reason was that patent holders accepted much lower prices. On the one hand, their bargaining position had worsened; on the other, they wanted to prevent an onslaught of generic production permits around the world.

The full truth is therefore that even though the WTO’s flexibility rules have hardly been used, their introduction 20 years ago had a vitally important impact. The insistence on the right to produce generics was effective in the sense of make vitally important HIV/AIDS drugs more affordable. As Achal Prabhala elaborates in our interview, however, the consensus reached in Doha was never fully accepted by the USA and the EU, and governments of developing countries have largely shied away from making further use of their multilateral victory.