Security

Digital surveillance

The “cyber harassment” offence in Uganda – Section 24 of the Computer Misuse Act 2011 – is defined as “the use of a computer in making obscene or indecent requests or threatening to inflict injury to any person or their property”. While intended to safeguard the citizens, many Ugandans actually feel this law puts them at risk because they may be accused of cybercrimes. This is especially true of journalists and other human-rights defenders (HRDs).

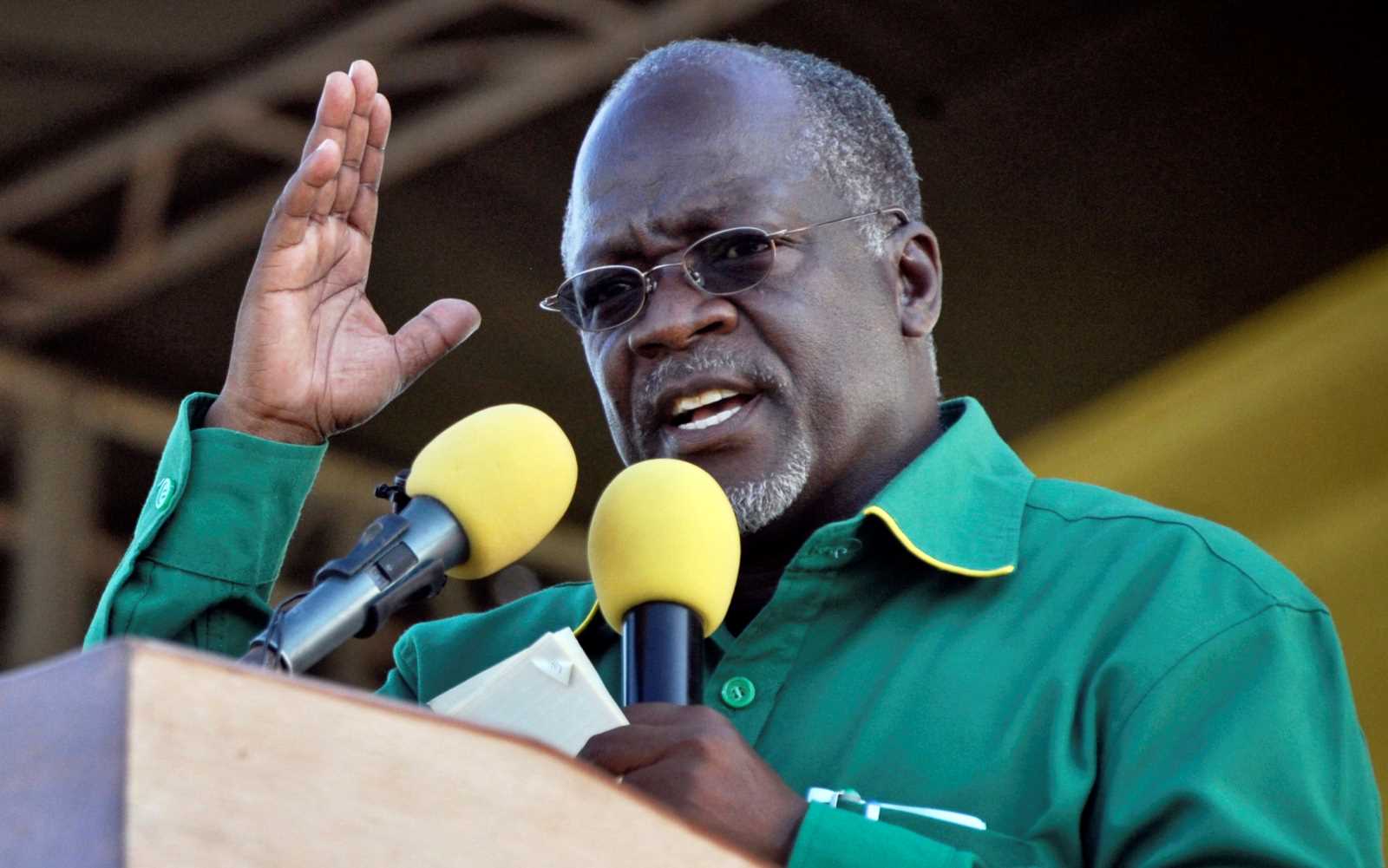

The currently most prominent victim is Stella Nyanzi, a university lecturer and feminist activist. On 2 August, she was sentenced to 18 months in prison for publishing messages on her Facebook page. Before, she had already spent nine months behind bars on remand. Her cyber crime was that she likened President Yoweri Museweni and his wife to a pair of buttocks in a post that dealt with gender issues in 2017. The judges now decided that she was guilty.

Eron Kiiza, one of Uganda’s leading human-rights lawyers, says that Nyanzi’s case shows that the Computer Misuse Act “is part of a policy to curb the freedom of expression”. Joan Nyanyuki of Amnesty International agrees. In her eyes, the verdict is “outrageous”. She maintains that the Ugandan authorities “must scrap the Computer Misuse Act, which has been used systematically to harass, intimidate and stifle government critics.”

Even when repressive state action does not cause lasting harm, its impacts are intimidating.

In 2018, seven journalists working for different media houses exposed a case of corruption in the bank of Uganda and published pictures of the questionable wealth of some directors in the Bank. The journalists were summoned by the police under the Computer Misuse Act to give their statements. Police later lost interest in the case because none of the implicated bank directors came out to accuse the journalists of any wrongdoing, thus the case was dropped.

Online crimes, online control

The Uganda Police Force has established an Electronic Counter Measure Unit (ECMU) with the mandate to detect and investigate crimes that are electronically or computer-generated; these are crimes committed using online platforms like Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, Twitter et cetera. The ECMU is the unit that oversees the implementation of the Computer Misuse Act.

Civil-society organisations see themselves as the major targets of this unit, and they claim that it is working in an extra-judicial manner. Under the Computer Misuse Act, security agencies may only conduct digital surveillance after getting the permission to do so from a judge. In most known cases of digital surveillance, however, such a court order never existed.

The Regulation of Interception of Communications Act (RICA) 2010 is another law that gives state agencies powers to intercept and carry out digital surveillance. Once again, RICA 2010 requires that the security agencies first seek court permission, but this requirement is rarely fulfilled, according to civil-society activists.

At the beginning of 2018, Uganda – with a population of 44 million – had 25 million mobile-phone subscriptions. Although the country has signed several international conventions that ensure freedom of expression like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the new laws are being used against individuals and organisations who are seen to be anti-establishment. Of course, those who investigate corruption are affected too.

Unwanted Witness is a Ugandan civil-society organisation advocating for digital rights. Its report “State of security for HRDs in a digital era” states that 97 % of journalists and human-rights defenders claim that they face digital threats and are subjected to online surveillance. Seventy-nine percent of them said they had no technical expertise to deal with the digital challenges and surveillance.

Dorothy Mukasa, the executive director of Unwanted Witness, argues that all threats to the enjoyment of online freedoms and rights in Uganda stem from the “existing cyber laws which are retrogressive”; they contravene the Ugandan constitution and do not meet international standards. “These laws are basically a tool used by government agencies to control and criminalise free speech,” Mukasa sums up. Together with other civil-society organisations, Unwanted Witness turned to Uganda’s Supreme Court in 2017. So far, there are no results of such legal action.

Powers to gather intelligence and conduct surveillance are concentrated in three institutions:

- the military,

- the police and

- the two secret services (external and internal) that report to the president.

Blocking Social Media

In 2014, the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC) established a media-monitoring centre, equipped with digital logger-surveillance equipment which record and analyse public radio, television and print-media messages.

Given the great influence social media has in the younger generation, the government is keen to monitor social media. Wilson Muruuli Mukasa, the former minister for security, has said publicly that the government established the social media monitoring centre “to sort out people who tarnish the government’s reputation” – meaning, getting rid of them.

On 18 February 2016, during the presidential election, the UCC ordered telecom companies to block all social media. Facebook, WhatsApp and Twitter were thus unavailable when voting results were being transmitted from rural constituencies to the Electoral Commission in Kampala. The opposition claimed that they were kept from transmitting the correct results. The intervention, they say, enabled the government to rig the election.

In June 2018, a social-media tax was introduced (see my contribution in D+C/E+Z e-Paper 2018/10, Focus section). Today, anyone who wants to access social media in Uganda must pay a daily tax of 200 Uganda Shillings (UGX) equivalent to 5 US cents. This tax does not control what is posted on social media, but it reduces their reach.

Journalists, civil-society actors and some politicians strictly opposed this tax. Some of them were arrested and charged for expressing their opposition in public. One of them was Robert Kyagulanyi, also known as Bobi Wine. His vocal criticism of the tax gives him a lot of clout amongst his young followers. He is now a member of parliament and is expected to run for president in 2021.

Security agencies are able to conduct surveillance on all mobile phone subscribers since SIM-card registration was made obligatory in 2012. All telecom companies and internet service providers are by law forced to ensure that their services are technologically capable of allowing lawful interception of communication in such a way that the target of the interception remains unaware of it, according to Section 8 of RICA 2010. Citizens cannot tell whether these capacities are misused or not – and many suspect they are.

The government has made a huge investment to procure and install CCTV (closed-circuit TV) cameras to monitor public spaces, especially in Kampala, the capital city. Some criminals have indeed been caught because their deeds were recorded. However, the same cameras are being used to track the movements of opposition politicians. Many people suspect that the Chinese government is helping the Ugandan government in this surveillance. The CCTV systems were supplied by the Chinese companies Huawei and ZTE.

Edward Ronald Sekyewa is the executive director of the media organisation “Hub for Investigative Media” (HIM). He lives in Kampala, Uganda.

edwardronalds16@gmail.com

Link

Unwanted Witness, 2017: State of security for HRDs in a digital era.

https://www.unwantedwitness.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/State-of-Security-for-HRDs-In-a-Digital-Era.pdf