Nation building

A challenge for a young country

The population of South Sudan is estimated at around 11 million. The world’s youngest nation is home to 64 ethnic groups who speak their own languages and maintain their own cultural practices. Thirty-six percent of the South Sudanese are Dinka. The Nuer are the second largest group with 16 %. The remaining percentage is distributed among smaller communities.

Many South Sudanese tend to strongly identify with their own ethnic group, which makes it difficult for the country to develop a national identity. It seems that when it comes to the question of what it means to be South Sudanese, we have not gone beyond superficial things like appearance. To be considered a true South Sudanese, you have to look a certain way: tall, dark-skinned and slim. I am short and not as dark as most of my compatriots, which has made some of them question whether I am really South Sudanese.

South Sudan seceded from Sudan in 2011 after more than 20 years of civil war. The war led to massive loss of life, the destruction of property and the displacement of millions of people. It left many traumatised.

Many people attribute the conflict between Sudan and South Sudan to ethnoreligious identities. The deep-rooted tensions between the Arab Muslims in the north and the predominantly Christian Nilotic ethnic groups in the south escalated into an endless war, as each side saw its culture and religion as superior.

Power, land and livestock

After the separation of the two countries, there has been no real peace in either of them – on the contrary, a devastating war is raging in Sudan. In South Sudan, too, ethnic tensions have not ceased with independence. Which ethnic group you belong to influences the political party you vote for, what opportunities you have on the job market and the social structure of entire cities. In addition, the ethno-political disputes and the competition between the elites of some ethnic groups for power and resources have put the country in an economic tailspin.

The two largest groups in particular, the Dinka and the Nuer, two pastoralist tribes originating from the Nile, have historically been rivals. Today, this primarily means competition for political power and repeatedly leads to violence and conflict.

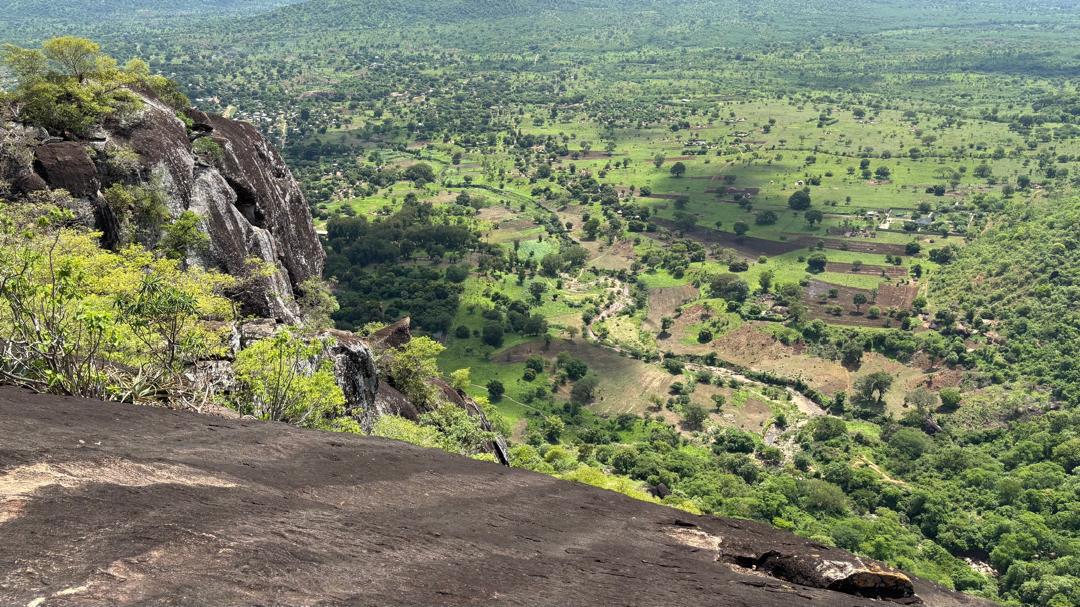

Conflicts over grazing land and livestock are rampant among other ethnic groups as well. The result is a seemingly endless repetition of violence and retaliation. For example, the state of Eastern Equatoria, a region that is home to more than 12 ethnic groups and subgroups, is notorious for cattle rustling and road raids between groups living close to each other. Although peace talks and negotiations have taken place, the conflicts prevent the region from developing due to the absence of security.

Divided diaspora

Tribalism moreover has a major influence on the labour market. It is a great advantage to be a Dinka to be employed by the government. So-called “Equatorian” groups from the east, centre and west have better opportunities in the private sector or with non-governmental organisations.

Ethnic identity also plays a major role in the South Sudanese diaspora. The ethnic groups literally stay together – the refugee and migrant settlements in cities and the refugee camps are organised according to ethnic communities. In Kenya, where many South Sudanese fled to and stayed after the war, Didinga are living in one particular town, while Kakwa live in the next and Nuer in the third. This cements tensions between the groups and further divides the South Sudanese instead of bringing the diaspora communities together.

Ethnic identity is central to preserving the country’s rich cultural heritage, but it is also important to address the challenges it has created in moving the nation forward. South Sudan needs a truly inclusive public discourse in order to implement policies that serve the interests of all citizens.

Alba Nakuwa is a freelance journalist from South Sudan based in Nairobi.

albanakwa@gmail.com