Migration in Africa

Life as a refugee in Kenya

I came to Nairobi in 2005 fleeing the civil war in South Sudan. I was eight years old. Now I am one of the 140,000 refugees from my country who, according to statistics of the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), currently live in Kenya. I knew from the start that my life in this new country would not be easy. But the horrific situation we fled from prepared most of us to be ready for pretty much anything.

We refugees are not the only link between South Sudan and Kenya. The two neighbouring countries have always had quite a lot in common. Several ethnic groups have a history in both countries, especially Nilotic speakers such as the Luo and Dinka. Today, moreover, both countries belong to the East African Community and thus have close political and economic ties.

Kenya has a long track-record of providing asylum and protection to South Sudanese. In 1983, a civil war between the central government of Sudan and the Sudan People’s Liberation Army broke out. That war ended in 2005, and South Sudan became independent. Nonetheless, the country is not at peace. Violent clashes between official security forces and rebel militias continue. According to the UNHCR, a total of 2.4 million people have been displaced.

Some South Sudanese have lived for decades in the infamous Kakuma refugee camp and its extension, Kalobeyei settlement, near the border between Kenya and South Sudan. I was lucky, because my stay there lasted only about a month and I could move to Kenya’s capital soon.

I felt privileged as well to be among those who had the opportunity to receive a full formal education, from primary school to university. Of course it was not easy to study in a foreign country. We refugee children typically spoke Arabic or local languages like Didinga or Laarim. The more English and Swahili I understood, the more things began to make sense to me. I also began to make more friends at school.

At first, I was scared of the new school and the new environment. Kenyan culture, however, is quite diverse, comprising at least 43 ethnic groups plus refugees from other countries like Somalia. Everyone is a stranger here from time to time and in different environments, so the interactions at school were quite natural. I soon felt well included.

Violence as a norm

Refugees receive UNHCR support to enrol in school. Many struggle nonetheless because they lack documents and proper guidance on how to proceed in the new system. Among refugees in Kenya, the number of school dropouts is indeed quite high. Financial stress is another reason for this. Although education in Kenya is mostly free at the primary level, it becomes difficult at the secondary and tertiary levels, where tuition charges cost considerable amounts of money. Here, too, I was lucky. I – and several other refugees – managed to complete a diploma course with the support of a German nun. But not everyone is that fortunate.

I consider peace and stability in Kenya a blessing. Most of us feel safe here. The Kenyan constitution contains clear guidelines and democratic principles, which in most cases serve to avoid conflict. The history of South Sudan, by contrast, is marked by war and violence.

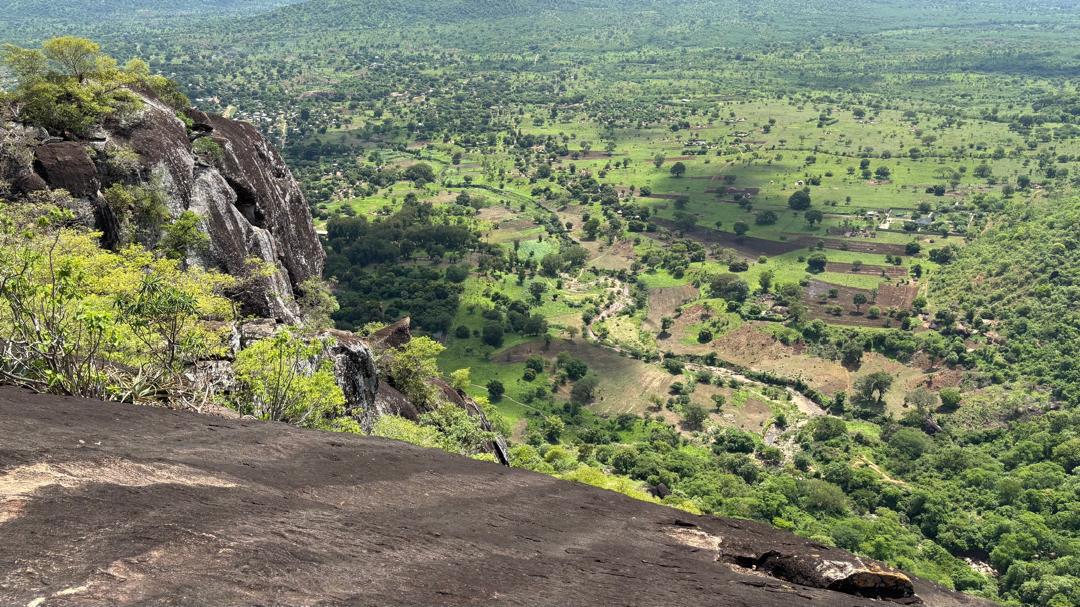

In Chukudum, the village where I was born, most people own one or two unlicensed guns. I have seen heated arguments among neighbours turn into cases of murder. Violence is a norm in South Sudan. Therefore, to live in Kenya freely without feeling threatened is Kenya’s greatest gift to me.

In Greater Nairobi, most South Sudanese live in rented flats. We are proud to be able to cater for the roof over our heads despite our refugee status.

However, our status has some downsides. Unemployment remains a major problem for many South Sudanese, even after getting university degrees, integrating into everyday life as much as possible and mastering Swahili and other Kenyan languages. Work permits are hard to get, and when jobs are available, Kenyan nationals are typically given preference.

The lack of legal documents makes it difficult to open bank accounts and receive medical services. Access to public health care is particularly difficult. We often end up paying more for treatment than would normally be expected. Unfortunately, there is discrimination in Kenya’s multi-ethnic society as well. We experience open neglect and isolation, but people also tell jokes or call us names to remind us where we come from.

Kenya’s 2021 Refugee Act inspires some hope that problems faced by South Sudanese and other refugees may be solved to some extent. For example, the bill affirms that refugees should be able to enter employment and also trade freely if they have the necessary qualifications.

The situation of refugees must certainly improve. Most refugees are young people with great potential. Kenya, South Sudan and other countries of origin could all benefit. It is a shame that this potential remains largely untapped. The refugee status keeps them from making a meaningful contribution to African society – and to the future of our planet in general.

Alba Nakuwa is a freelance journalist from South Sudan based in Nairobi.

albanakwa@gmail.com