Climate justice

Climate justice cannot be left to market dynamics

The science is absolutely clear. The escalating climate crisis means that humanity is heading for disaster. One after another, the assessment reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) have pointed this out. The outlook is becoming ever more frightening. In number six, the picture remained bleak even in the most optimistic scenarios. It is truly amazing that these reports, which are based on historically unprecedented efforts to compile all relevant studies internationally, have not triggered credible and effective responses.

Policymakers clearly know what is at stake, not least due to the annual UN climate summits. The recent Glasgow summit, delayed by one year because of Covid-19, was attended by almost 200 countries. Mass media reported what risks we face and what needs to be done. Nonetheless, we still lack credible and effective responses. “Our fragile planet is hanging by a thread,” said UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres in his closing remarks and added: “It is time to go into emergency mode – or our chance of reaching net zero will itself be zero.”

Occultist market orthodoxy

Extremely powerful forces are at work. Those who benefit from fossil capitalism are pushing humanity towards the abyss. Corporate investors prioritise profits, not the common good, while market-orthodox ideology disparages state action. Governments in the global north and south, whether elected or not, seem enthralled by a kind of occultist cult that praises the private sector.

The real challenge is to steer economic activity onto an environmentally sustainable trajectory. This will require decisive action, and setting market incentives will simply not be enough. Nonetheless, multilateral debate largely sticks to economic paradigms that confront or question corporate power and shy away from regulating it stringently.

At the same time, corporate rhetoric has been changing. For example, the finance-sector giant Black Rock has been demanding more government spending on climate protection. Moreover, many multinationals have adopted some kind of sustainability programme. None of this means much because we lack criteria to detect green washing.

What we need is a transformation of the global economy, but what companies offer is well-designed PR plus new business models, some of which may actually do some good, some of which are designed to attract subsidies and some of which may even prove harmful. To only mention one snag: Many companies promise to offset greenhouse-gas emissions by planting trees. That may work out for a single enterprise, but not all can do so. There simply is not enough land for the large-scale global afforestation that would be required.

Green deals

More must happen than is currently on policymakers’ agenda. There is a trend to draft green deals, and documents of this kind are proliferating. The bad news is that they are not up to task.

The general idea is to follow the example of US President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. It relied on massive government spending to generate employment, create infrastructure and offer new opportunities to masses of people, ending the Great Depression of the 1930. Today’s green-deal proposals often link escaping the Covid-19 slump to environmentally needed investments and greater social justice.

Unfortunately, the green deals tend to stay unconvincing. US President Joe Biden’s Green New Deal is stuck in the Senate (see Katie Cashman on www.dandc.eu), and even if it were implemented, it would not suffice to make the US environmentally sustainable. The EU, in the context of its European Green Deal, has recently accepted nuclear energy and natural gas as “sustainable” options, even though the first causes unmanageable radioactive waste and the latter is a fossil fuel. Observers from less fortunate world regions notice that those who claim to be global leaders struggle to wean their own nations off excessive resource consumption.

It is disturbing, moreover, that green deals tend to be embedded in orthodox economics. They fail to question the accumulative greed of capitalism, which is the biggest cause of environmental destruction. Too many authors do not take into account that unlimited growth is impossible on a planet with limited resources. Instead, green deals rely on green bonds, carbon credits and similar tools to create new options for capital accumulation. Infantile faith in market mechanisms is de-politicising and de-historicising global discourse.

Not all green-deals proposals are the same. Some include progressive ideas for promoting social justice and reducing inequality. Sensible visions of democratic eco-socialism are geared to tackling environmental and socio-economic challenges at once. Authors such as Max Ajl (2021a, 2021b), John Bellamy Foster (2020) and Tom Perez (2021) have done good work in terms of assessing things.

Glaring inequality, worsened by growing environmental hazards

It cannot be disputed that humanity needs global policies in response both to glaring inequality and worsening environmental hazards. A serious global green deal in pursuit of social and ecological justice would be good. Unfortunately, we lack the kind of global-governance system that might conceive, adopt and implement it. What we have are many different multilateral institutions with different agendas and different shareholding patterns. Most of them fail to deliver the results we need.

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change is a striking example. The international community adopted it unanimously three decades ago. The annual climate summits are supposed to improve and implement it. Yes, we have undeniably seen some incremental progress, but the big picture is that the climate crisis has kept escalating. It will soon spin out of control. In spite of the UNFCCC, we are heading towards eco-cide and bio-cide.

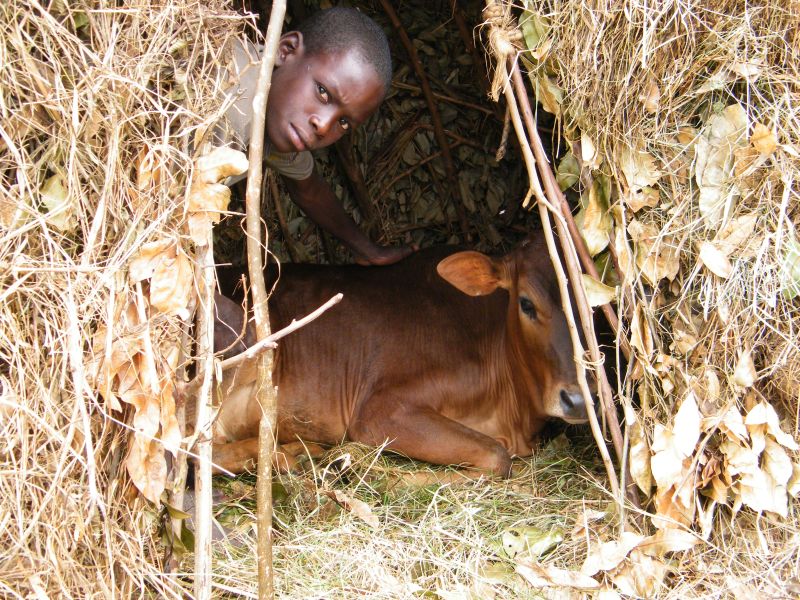

Climate justice is needed at the global level. So far, low-income countries – and especially the poor communities who live there – have felt the worst impacts of global heating. By contrast, the high-income countries, which have emitted by far the most greenhouse gases since the industrial revolution, are better placed to adapt to a changing environment. Compounding global justice problems, high-income countries wield disproportionate power in multilateral settings, but regularly fail to fulfil their promises (see Saleemul Huq on www.dandc.eu).

To keep average temperature increases below 1.5° Celsius, humanity must accept a finite carbon budget. Approximately 70 % of it has been gobbled up by a handful of countries in the global north. China has recently joined the list of big guzzlers. What about the 70 % of the world population who live in other countries – most in the global south – and are largely deprived of material progress?

Phasing down versus phasing out

The insistence of India’s government to keep on using coal must be seen in this context. This step has attracted considerable criticism because it made sure that the final statement in Glasgow only called for “phasing down” coal rather than phasing it “out”. There is much to dislike about Prime Minister Narendra Modi who is not a champion of social justice. At the domestic level, his policies tend to serve Hindu majoritarianism and exclude minorities. Nonetheless, his government’s stance in Glasgow regarding coal made sense. Low and lower-middle income countries must not be made to bear the main brunt of mitigating the climate crisis. If the EU thinks it still needs gas, India will certainly still need coal.

The challenges are complex and huge. It is impossible to fully assess them in a short essay as this one. It is obvious, however, that we need decisive action and that technocratic market interventions cannot suffice. Harmful patterns of production and consumption must be banned. At the same time, disadvantaged communities must not be left even further behind. We need ecological and social justice.

People around the world are indeed rising up in big and small movements. They want to fight for social justice and against environmental destruction. The climate strikes that were initiated by Greta Thunberg, the Swedish teenager, proved that climate worries resonate all over the world. Such activism inspires hope. Doomsday fatalism will not help us. At the same time, eco-activism has not brought about the change needed. Thunberg had a point when she summed up the Glasgow climate summit as yet more “blah blah blah”.

References

Ajl, M., 2021: A people’s green new deal. London, Pluto Press.

Foster, J. B., 2020: Return of nature: socialism and ecology. New York, NYU Press.

Perez, T., 2021: Green new deals in a time of pandemics. Barcelona, ODG – free download at:

https://odg.cat/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/GREENDEALS-ENG_ONLINE.pdf

Praveen Jha is a professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi.

praveenjha2005@gmail.com