Agriculture

Valuable farmland

In all climate zones, agriculture needs sufficient soil that is moist, healthy and mineralised. Suitable land for agriculture is becoming increasingly scarce however. Worldwide, the loss of fertile soil directly affects approximately 1.5 billion people who depend on agriculture. About 42 % of the people in developing countries make a living on degraded land that is not really suitable for agriculture anymore, IFPRI and ZEF report.

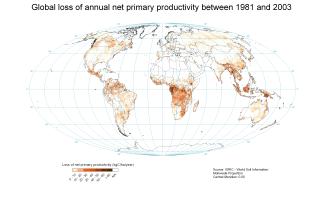

The world population has grown significantly over the past 30 years, and so has the consumption of agricultural products. The amount of land for agricultural production cannot increase however. Boosting crop yields temporarily bridged the gaps. As the scholars point out, the yield increase has recently slowed down. Moreover, climate change is likely to reduce farm productivity in many parts of the world. In these circumstances, “increasing land degradation is something the world simply cannot afford,” the authors write.

Waterlogging, compaction, crusting, acidification and nutrient imbalances can deplete soil fertility quickly. Hot, dry regions are prone to bush fires, a natural phenomenon that triggers soil erosion. Erosion and salinisation are also consequences of low and rare rainfall as well as unpredictable monsoons. Inappropriate and unsustainable agricultural practises similarly speed up the loss of soil. Deforestation, overgrazing, cultivation on steep slopes and bush burning are among the main causes of land degradation the experts explain.

The causes of land degradation are thus numerous and complex. The authors argue, however, that land degradation is the result of political and institutional failure. Many farms are operated in hardly profitable and environmentally destructive ways, they state, because the farmers lack adequate information, land rights and access to credit.

According to the authors, national and international policymakers need to set clear signals for sustainable land management. Moreover, the protection of arable land and water resources are considered to be of equal importance.

It is very expensive to tackle the negative physical effects of soil degradation. Doing so tends to increase the costs of agricultural production considerably. The scholars warn that rising land prices must not be misunderstood as an opportunity for financial speculation. The real message of rising land prices, according to them, is that land is an essential commodity.

Land serves a great variety of functions, preserving the living conditions on earth. Examples for such “ecosystem services” include the provision of food, water and clean air, the regulation of floods and diseases and dependable nutrient and water cycles. There are cultural dimensions to ecosystem services too, relating to medicine or spirituality for instance.

The ZEF and IFPRI authors bemoan that, to date, most ecosystem services are taken for granted, so their real value is underestimated. There is no market for these services. Land degradation is a consequence of market prices not reflecting their worth. To change matters, the economic value of these services must be determined, the authors advise, so decision-makers can take it into account.

Any sustainable, environmentally responsible growth strategy must be degradation-neutral, the study argues. In other words, land degradation must be either avoided or offset by land reclamation. Such an approach must fit biophysical science, and it needs an economic underpinning, the scholars conclude.

Floreana Miesen