Summer Special

“I belong here!”

The debate regarding where people belong is not a German peculiarity – it is a global debate. In China, for instance, the Uigurs, a Muslim minority, are being discriminated against by the state; Israeli Palestinians cannot move freely in their own country, and in Myanmar, members of the Rohingya ethnic minority are simply considered as foreigners and denied citizenship. Who belongs to a country and who does not is generally being decided by the biggest ethnic or religious group. Where there is no democracy, minorities are in trouble.

Germany is a country of immigration, and its constitution guarantees religious freedom. People of diverse ethnic and religious groups live in Germany. But this is not so self-evident for everybody. Often, the rightful belonging of a person is put into doubt – for instance with the frequently posed question: “Where are you from?”

The German journalist and author Ferda Ataman has Turkish parents, grew up in Southern Germany and lives in Berlin. In her recently published book, she discusses all sorts of misunderstandings regarding immigration.

Ataman considers the obnoxious question about her origins not as a sign of interest, but of exclusion: “This shows where the enquirer places me: as a non-German. Not belonging.” In and of itself, this is no problem, she clarifies – but considering the structural discrimination of minorities, this difference matters.

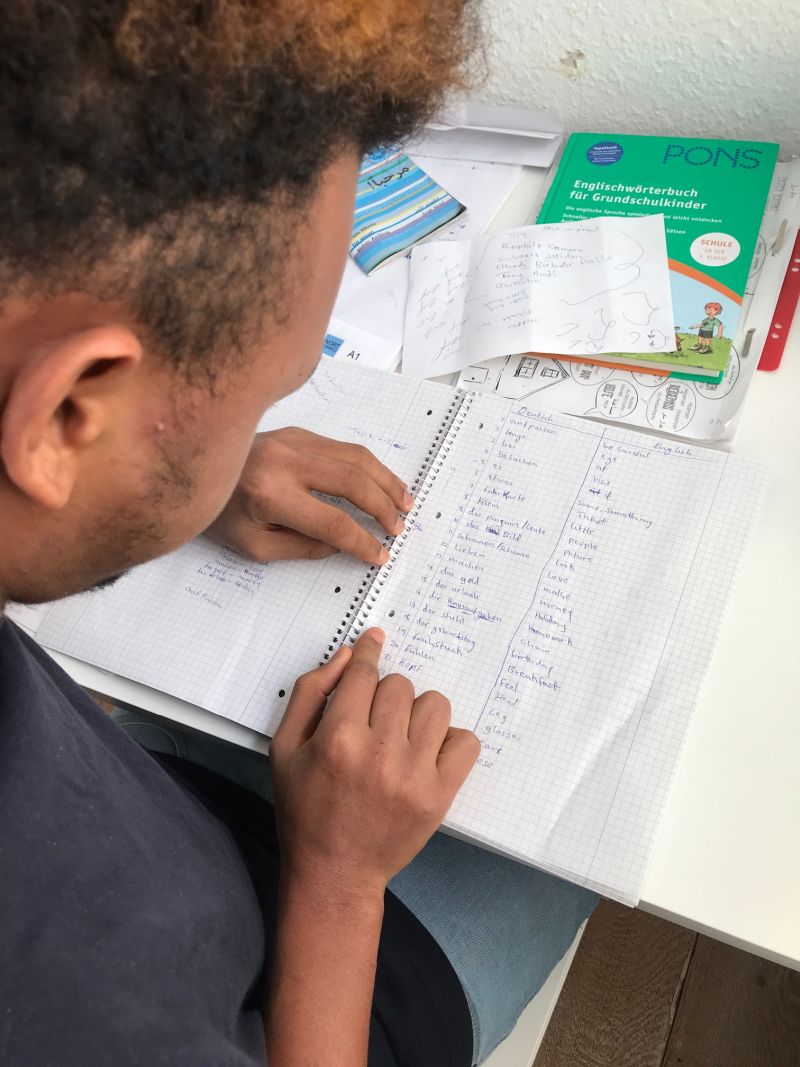

Ataman points at studies by the OECD, which unequivocally show that children of immigrants’ families are being discriminated against in German schools: for example, they have a five times smaller chance to enter a high school than a German child – with equal academic performance!

There are countries like the USA or India, which counteract the structural discrimination of minorities with “affirmative action”, for instance, by reserving a certain number of university places for them. In both countries, however, these policies are being questioned since quite some time.

Ferda Ataman analyses in her book the German debate regarding integration. Even second or third generation immigrants “are considered to have the obligation to fulfil, to assimilate perfectly” – but the criteria for this change permanently. “Apparently, integration has no aim: we will never be real Germans. So why join the game?” she asks polemically.

The debate around identity and belonging is no mere intellectual banter. For populist parties all over Europe, this is a focal point of their agenda: migration is a crucial topic for bargaining political positions. Right-wing parties push for a strong national state – and this should be aligned along an ethnic homogeneity. “In Germany, our perception of belonging has a lot to do with genes,” Ataman writes. “Germans are those who were here first and therefore always belonged here. Many believe that there is a native people (‘Germans’) that does not change, even when immigrants come on board.”

The demand for an ethnic and religious homogenous national state is not being spelled out clearly, but is disguised in the debate around the issue of homeland. And exactly at this point, it is taken for granted that people from migrant families always locate their home in countries abroad. Ataman comments: “Homeland is for most people a place or a feeling. But if politicians want to exploit feelings, they should focus on those that look into the future and not the past.” That is the forte of this book: it is directed towards the future and offers suggestions for an improved coexistence.

Book

Ataman, F., 2019: Hört auf zu fragen – Ich bin von hier! (Stop asking – I belong here!) Frankfurt a. M., S. Fischer (only available in German).