Motherhood

Healthy change

Bangladesh is the regional front runner. The World Bank reports that the TFR was 6.6 in what was then East Pakistan in 1960. The rate has since been reduced by more than two thirds. The achievement is important because sustainable development requires a stable population.

In Bangladesh, the first family-planning programmes were launched in the 1960s. They did not deliver impressive results. An important reason was that they focused entirely on contraception methods, but failed to tackle issues of maternal and child health as well. What really encourages parents to opt for smaller families is lower infant and child mortality. If they think some of their children will die, they want to have several to make sure that some survive. If they expect their children to live, however, they want to invest in their education to maximise their chances in life. On average, healthier families are therefore smaller families.

After independence from Pakistan, Bangladesh ran very successful vaccination programmes. Moreover, basic health services began to improve, mostly due to non-governmental efforts. However, the government also recognised the need to focus on maternal and child health. More children than before lived beyond their fifth birthday.

Experience shows that close cooperation of state institutions and civil society is useful. In 1978, the Bangladeshi government started to promote family-planning services through family-welfare assistants, most of whom were professionally trained paramedics, nurses and birth attendants. Their job was to reach out to village women at the grassroots level. The point was to advise mothers about the benefits of having a small family, but they offered comprehensive advice on other things and helped families to get access to competent health care.

Bangladesh is a least-developed country. We do not have enough medical doctors. As the experience of Gonoshasthaya Kendra (GK), a non-governmental health-care provider, and others shows, however, paramedics can provide most essential health services. For complicated cases, of course, they need a referral system with professional doctors.

Especially in rural areas, traditional midwives have always been important – and they still are. They enjoy the trust of their communities. It makes sense to update their knowledge and involve them in family-planning promotion.

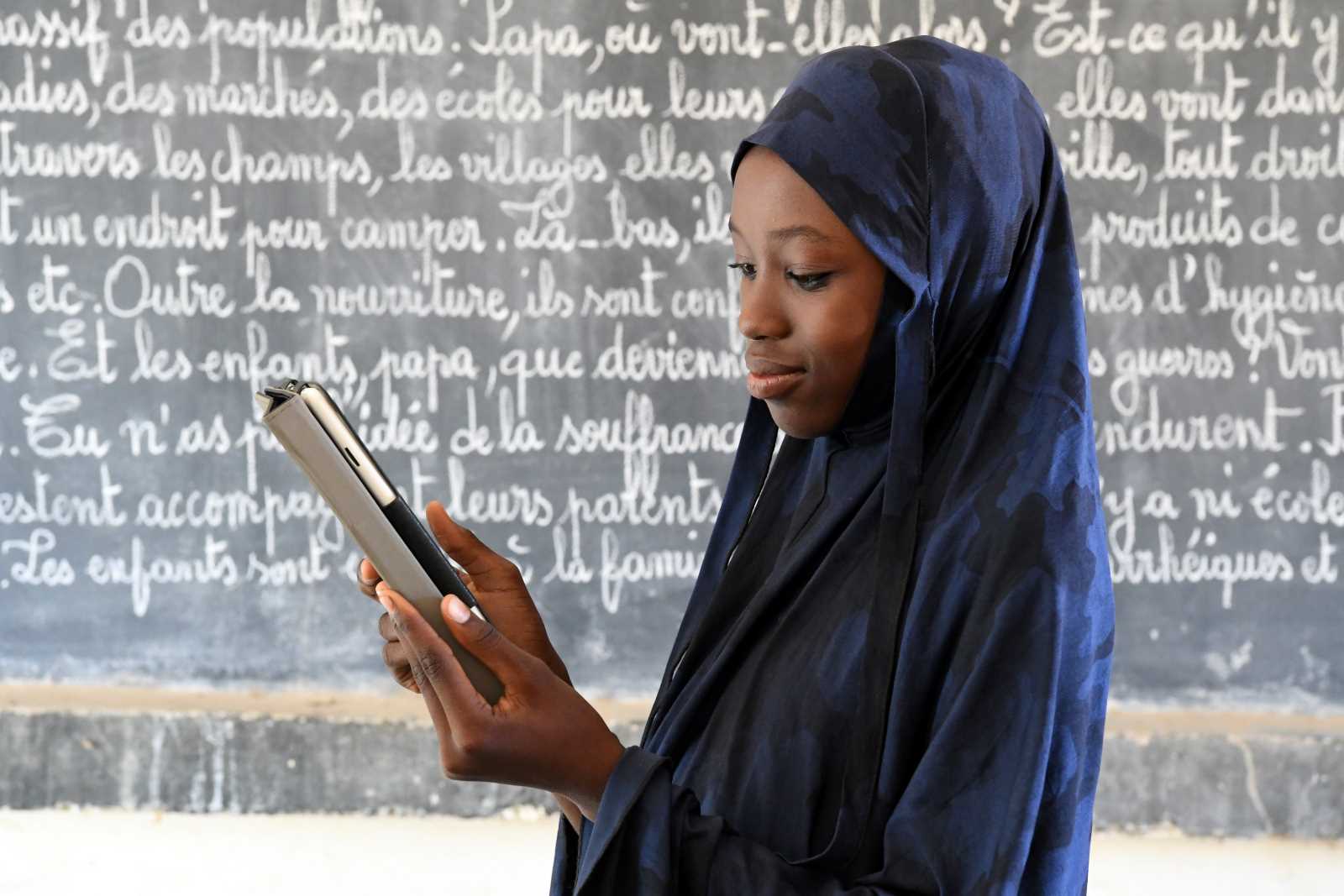

Education gives women more decision-making power about how many children to bear – and girls who go to school tend to get married later. Moreover, gender roles are changing – not least thanks to micro-finance organisations. They have been giving women access to credit for decades.

It is noteworthy that religion was not a major obstacle to promoting birth control in Bangladesh. Our recent history probably played a role. In the liberation war of 1971, many women were raped, and some became pregnant. They did not want the babies of the oppressors, so they needed abortions. Even though our country is predominantly Muslim and has a rather conservative culture, people sympathised with the pregnant rape victims. The humanitarian catastrophe actually provided an opportunity to take a progressive approach to family planning. Religious clerics did not pose a threat to family-planning efforts as they did in Pakistan.

Bangladesh is still a poor country, but we have made some progress. The vast majority of people enjoy food security today, but the poor suffer malnutrition. Masses still lack appropriate shelter. Due to rural poverty, cities are growing fast without proper infrastructure. Impacts of climate change are being felt. Future challenges are daunting, but not insolvable.

It is a great achievement that Bangladesh has lowered the TFR to 2.1. However, average data always hide some issues. The fertility rates are still higher for poor families in rural areas. Health-care services must improve further – and so must social and physical infrastructure in general.

Najma Rizvi is a professor emerita of anthropology of Gono Bishwabidyalay, the university started by GK, the health NGO.

nrizvi08@gmail.com