Multilateralism

The role of BRICS+ in development and climate finance

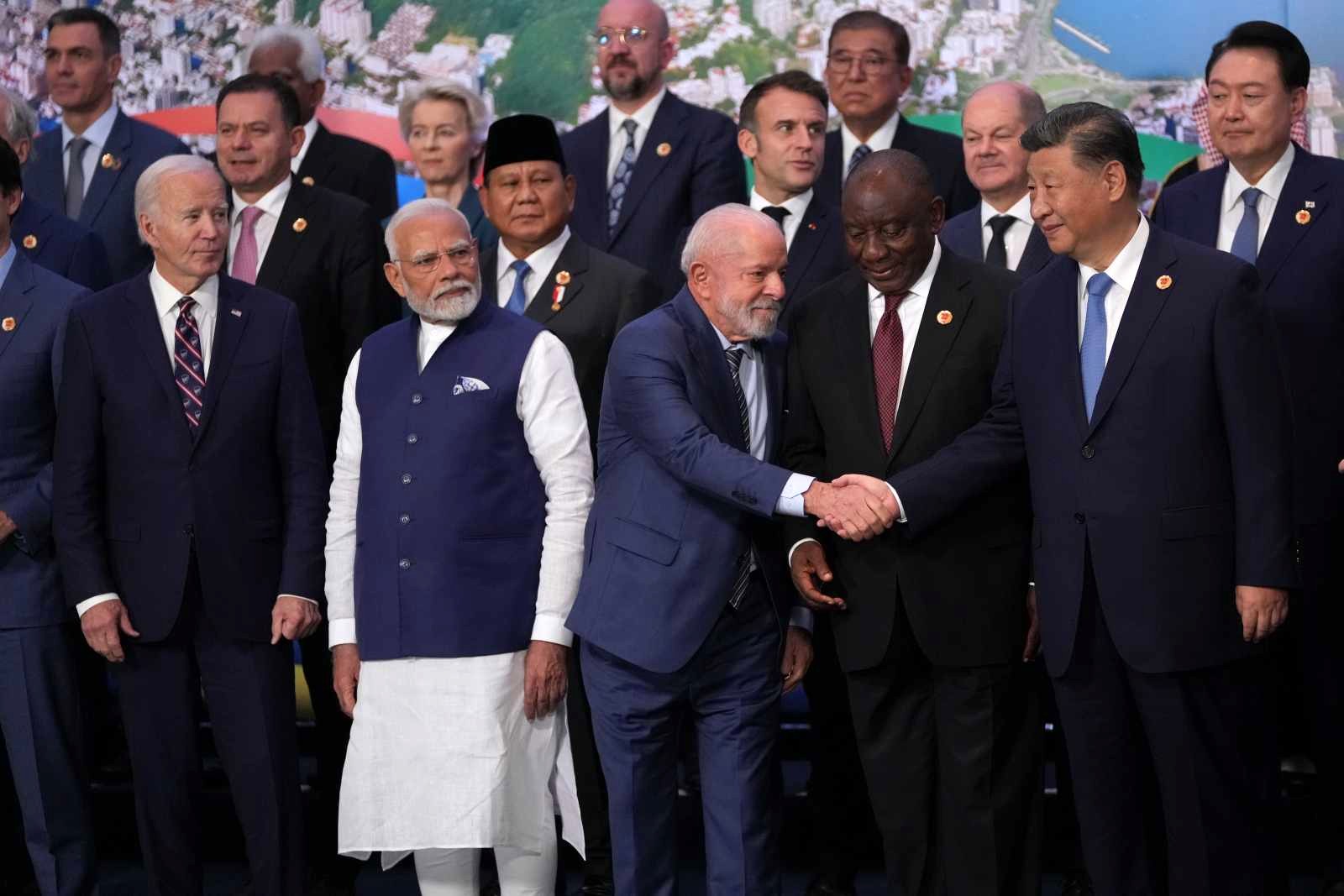

The BRICS+ are made up of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, joined by Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Indonesia and UAE. The group plays a pivotal role in global development and climate finance. With roughly half of the global population and about 40 % of global GDP, the BRICS+ have the potential to collectively shape the global financial architecture and targets. In addition, BRICS+ members have historically accounted for a considerable share of global carbon emissions in absolute terms.

The origins of the group are closely linked to efforts to reform post-war international financial institutions, particularly the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The founding members considered these reforms carried out since 2010 inadequate, however. Specifically, they failed to redistribute decision-making powers in these institutions between countries. They remain heavily skewed towards OECD countries – especially the US, the only country with veto power in both the World Bank and the IMF.

As a response, the BRICS chose to create their own financial institutions. The New Development Bank (NDB) aims to bridge the infrastructure investment gap in the global south, and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA) is designed to protect members from global liquidity pressures.

BRICS+ and climate finance

Following last year’s Climate Agenda in Modern Conditions Forum in Moscow, the BRICS adopted a framework document on climate and sustainable development that includes key aspects of climate action, such as a just transition, mitigation, adaptation and carbon markets. The bloc also recognises the legitimacy of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), including the annual Conference of the Parties (COP) sessions.

While the need to switch to renewable energy sources plays a key role at climate conferences, the share of fossil fuels in the energy mix remains high in some BRICS countries. Among the four original BRIC and South Africa, South Africa has the highest share (94 %), followed by India (89 %), Russia (87 %) and China (82 %). Brazil’s share is only 49 %, mainly because the country makes extensive use of hydropower.

While climate finance has been increasingly detached from development finance in recent international negotiations, some of the BRICS+ see them as inextricably linked. In their view, climate finance is an integral part of development finance. The bloc is also concerned with attempts to link international security issues with climate finance and the climate agenda.

The BRICS+ are in favour of increasing funding to help the most vulnerable countries achieve their climate goals and adapt to climate impacts. The group also calls for better access to concessional loans from development banks and unconditional lending, and advocates more for funding for adaptation to climate change than for decarbonisation.

With the exception of Russia, the BRICS+ countries form part of the G77, the coalition of developing countries in the UN system. As part of this group, they endorsed the call for $ 1.3 trillion of annual climate finance by 2035 that was made at COP29 in Baku last year. Similarly, they emphasised the need to channel these resources through public grants, as opposed to loans and private finance. However, COP29 fell short of the $ 1.3 trillion target and set it at $ 300 billion instead.

BRICS+ might fill political void

The withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement following Donald Trump’s election has created an opportunity for BRICS+ economies – especially China – to fill the political void. China continues to strongly resist being grouped with the US and other high-income economies which are obligated to donate to climate finance under the Paris Agreement. However, it is already one of the world’s largest investors in climate action in the global south – even if it almost exclusively privileges methods of lending that ultimately benefit its own economy.

Brazil will host COP30 in the city of Belém in November this year. The country will therefore play a decisive role in shaping climate financing mechanisms. Brazilian representatives have spoken out in favour of mechanisms that focus on the specific needs of developing nations and thus are expected to campaign for social and environmental justice at COP30. It is doubtful they will succeed, however. Many observers have criticised the inadequate results of previous COPs and the structure of COP itself.

BRICS+ in development finance

The Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development (FfD4), which will take place between 30 June and 3 July in Seville, Spain, came about mainly thanks to the efforts of the G77. Reforming multilateral financial institutions was the original and most important goal of the BRIC, and it will continue to be one of the bloc’s priorities at FfD4. But multilateralism is clearly no longer high on the international political agenda.

BRICS+ countries and developing countries outside the bloc have long pressed the UN to lead negotiations on international taxation arrangements to provide more financial resources for development. During its G20 presidency in 2024, Brazil proposed that a global tax rate of two percent be imposed on billionaires. Donald Trump will undoubtedly oppose such a measure, however.

Excessive public debt is another core problem of development financing. According to the OECD, the number of countries in debt distress increased from three in 2015 to 11 in 2024, while the number at high risk of debt distress rose from 16 to 24 (OECD 2025). The UN points out that about 40 % of the global population live in countries where governments spend more on interest payments than on education or health. In their 2024 Kazan Declaration, BRICS+ recognised the need for greater debt relief and called for the implementation of the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatment “with the participation of official bilateral creditors, private creditors and Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) in line with the principle of joint action and fair burden-sharing.”

Weakening the influence of the dollar

The BRICS+ also seek to reduce their dependence on the dollar. Their immediate goal is to abandon the currency in their bilateral transactions and aim for a more diversified monetary system. One reason is that the US has imposed financial sanctions on Russia, which many see as an example of the “weaponisation” of the dollar – the idea that the US is using the world’s most traded currency to consolidate its geopolitical and geoeconomic dominance. China and Russia in particular have challenged this dominance, and the new BRICS+ members are strengthening the organisation’s anti-American tendencies.

However, in February, India and Russia announced that the BRICS are currently not working on developing a common currency. They issued these statements after Donald Trump threatened to impose 100 % tariffs on BRICS member countries if they tried to supplant the dollar.

Challenges facing the BRICS+

Global finance has always been the area where BRICS’s interests have been most aligned and where they have had their greatest success. However, the member countries do not agree on all issues related to development and climate finance. For instance, in 2023, Brazil proposed the creation of a common currency for trade and investment among the BRICS, but other member countries, most notably India, opposed this proposal. Crucially, the expansion of the BRICS group has significantly exacerbated the collective action problems that have always plagued the bloc.

There are also considerable asymmetries in economic and political power within BRICS+. China tends to prevail in most decisions, including those relating to the expansion of the bloc itself. As a result, with the support of Russia, China has managed to increasingly turn BRICS+ into a force to oppose US hegemony. This is uncomfortable for members that are more dependent on the US and creates new challenges for joint action. As geopolitics permeates (and subordinates) all other issues on the international agenda, including global finance, these tensions are intensifying.

Finally, while Trump’s aggressive nationalistic threats and policies certainly challenge the BRICS+ individually and as a bloc, they also open up opportunities. The US’s decision to increasingly prioritise perceived national interests over multilateral cooperation may free up space that the BRICS+ could take advantage of. Indeed, the bloc could find new ways to exert influence and shape future agendas and institutions.

Links

XVI BRICS Summit Kazan Declaration, 2024:

dirco.gov.za/xvi-brics-summit-kazan-declaration-strengthening-multilateralism-for-just-global-development-and-security-kazan-russian-federation-23-october-2024/

OECD, 2025: Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2025.

oecd.org/en/publications/global-outlook-on-financing-for-sustainable-development-2025_753d5368-en/full-report.html

André de Mello e Souza is an economist at Ipea (Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada), a federal think tank in Brazil.

X: @A_MelloeSouza