MENA

Two peoples’ experience of displacement

Israel was founded with a UN mandate in 1948. The background was the Nazi genocide. The idea that Jews needed a state of their own to feel safe was broadly accepted.

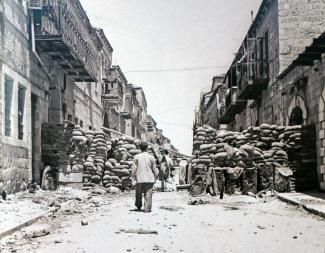

The UN had also foreseen a separate sovereign Palestinian state, but the despots of neighbouring Arab countries did not want that to happen. They thought they could get rid of Israel immediately, but they lost the war they started on the occasion of Israel’s independence. As a result, Israel conquered additional territory.

The conflict was bizarrely asymmetric from the very beginning. Things would probably have been different had there been something like a Palestinian nation in the 1940s. There wasn’t. As a matter of fact, many Arab countries still lack the kind of nationhood that means that people share a sense of identity which obliges them to mutual respect and solidarity.

The background is that Arab borders were rather arbitrarily drawn at the end of the imperialist Ottoman empire. Society was basically feudal, with city-dwelling absentee landlords exploiting illiterate peasants. It thus wasn’t unusual for Palestinian farmers to work for landlords who lived far away, in Damascus for example.

Feudal mentality and absentee landlords

Before Israel’s independence, such absentee landlords had sold land to Jews, with the result of Arab farmers losing their livelihoods. The new Jewish owners and their families did the farm work themselves. Moreover, Bedouin communities added a sense of anarchy because they did not stay in one place.

The Jews who had settled in Palestine and created Israel, by contrast, had a strong sense of nationhood, solidarity and mutual support. Socialist ideas from Europe were very common. Men and women were literate. People appreciated formal education. At the same time, the Jewish community had a strong culture of public debate, which provided space for expressing dissent in a context of solidarity.

Post-Ottoman Arab countries, in comparison, were rather rigidly authoritarian and hierarchical. An important reason why Israel’s army triumphed in 1948 was that its soldiers were defending their nation, whereas Arab soldiers were only really serving their leaders.

While pan-Arab agitation did little to help Palestinians, it did lead to persecution of Jews from Iraq in the east to Morrocco in the west. Jewish communities have largely disappeared from Arab countries.

It is estimated that some 800,000 people were forced to flee, and their obvious destination was Israel. Their expulsion from Arab countries obviously did not alleviate Palestinians’ suffering. They paid a heavy price for the Arab defeat in 1948, when 700,000 or so were displaced. Their descendants still speak of the “Naqba”, which means catastrophe. Others were displaced in later wars which Israel again won.

Most of the descendants are still refugees who lack citizenship of any state. The West Bank and Gaza have been occupied territories since 1967. Israeli settlements are spreading in the former area, and formal security forces protect them. Their infrastructure is far better than that of Palestinian villages. The Israeli government has publicly announced its intentions to annex large areas. Serious grievances thus persist.

It is true that Israel has a history of displacing Arabs. What is less-well known and gets totally lost in anti-Zionist agitation, however, is that about 50 % of Israel’s population is originally from the MENA region. Like the survivors of the Nazi genocide, the Jews that fled Arab countries have a history of violence displacement.

As peoples, both Israelis and Palestinians share the experience of discrimination, oppression and forced migration. As the Israeli scholar Yuval Noah Harari has pointed out, both sides have empirical reasons to believe the other wants to destroy them. Accordingly, peace building is extremely difficult. I’ll return to the issue below.

No real pan-Arab solidarity

From the 1970s on, governments of neighbouring Arab countries later more or less abandoned the Palestinian cause. They actually did not have a good track record of taking care of their own people. The problem is that strongmen anywhere tend to defend their power, suppress the opposition and surround themselves with cronies. That was no different in North Africa and the Middle East.

While Arab countries suffered stagnation, Israel became a prospering and dynamic economy. Of course, foreign direct investment, particularly from the US, helped, but the institutional landscape mattered too. It was missing in the Arab world, which as a whole did not lack funding. Indeed, the region might look different today, had the oil monarchies of the Gulf invested more in Arab development instead of basically entrenching their absolutist power and exploiting natural resources to the benefit of royal families. The full truth is that pan-Arab rhetoric served despots’ authoritarian needs but did not lead to tangible pan-Arab solidarity.

The rise – and divisiveness – of political Islam

Frustration with authoritarian leaders eventually led to pan-Arab ideology becoming largely irrelevant, while Islamist groups became more influential from the late 1970s on. Again, however, it was not really about pan-Muslim solidarity. There are three different brands of political Islam that vehemently disagree with one another. The Wahhabis, the Muslim Brothers and Iran’s theocracy have very little common ground. The consequences have been dreadfully bloody in some places, especially Syria.

In Palestine, however, the shared history of displacement and oppression fostered a sense of Palestinian nationhood. To alleviate the people’s suffering, the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) decided to stop the armed struggle and make peace with Israel. Hamas, which has roots in the Muslim Brotherhood, disagreed and opted for violent subversion. Today, things look worse for Palestinians than ever before.

Hamas’ Islamist ideology has led to deadly terrorism. This outfit opposes peace and wants to eliminate Israel. For this cause, it is willing to sacrifice thousands of its own people’s lives.

Western observers, however, tend to neglect the fact that right-wing extremists in Israel have a history of making peace impossible too. Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was murdered by an Israeli, not an Arab, for example. Violence perpetrated by Israeli settlers on the West Bank keep feeding Palestinians’ Naqba narrative which revolves around displacement.

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have spelled out in detailed reports why they accuse Israel of apartheid. One need not necessarily agree with the term but should not dismiss such criticism as mere anti-Semitism. The reports deal with Israeli state action and are not concerned with Judaism as a faith or as an ethnic identity.

Palestinians are still politically divided. There has been deadly violence between the PLO and Hamas in the past. It also matters, that people live in very different socio-political conditions in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, Gaza and Israel itself. All four areas have sizeable Palestinian populations.

Israel’s Palestinian citizens

It is ironic, to put it mildly, that for decades Palestinians with Israeli citizenship were the Arab community with the most civic liberties in the world. While Arab Israelis do face discrimination and have reason to feel they are only second-class citizens compared to Jews, they are represented in Parliament, enjoy the freedom of speech, are free to organise and to hold assemblies. Before the Arab Spring, Palestinian Israelis had more civic rights than were granted in any Arab country. With Tunisia’s regime becoming increasingly authoritarian, that may actually be the case again today.

Palestinians in East Jerusalem never got citizenship after Israel annexed that part of the city, breaching international law. They only have permanent rate of stay, and they lose it, if they spend too much time outside Jerusalem. Israel’s planning system discriminates against Palestinians no matter where in the four different jurisdictions they live.

The really bizarre thing, however, is that Hamas and Netanyahu both have long relied on their “violent coexistence”. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has a history of making the PLO look weak and corrupt while maintaining an awkward cooperation with Hamas. His hardline militarism thrived on occasional skirmishes with the hostile militia, but apart from those skirmishes, he did nothing to weaken Hamas. His overarching goal was to stay able to tell western allies that he simply had no partner for making peace.

Left to themselves, Israel and Palestine are unlikely to make peace. Mutual resentments are deeply entrenched. Both sides have suffered brutal violence in the past. There is precious little trust. The implication is that peace will certainly depend on international mediation. Given that the multilateral system is increasingly polarised and was never strong enough to ensure the kind of global governance we need, that seems hard to accomplish. Without peace, however, the deadly violence will continue to haunt both Israelis and Palestinians.

Hans Dembowski is the editor-in-chief of D+C/E+Z.

euz.editor@dandc.eu