Colombia

Colombia offers displaced Venezuelans residence and work permits

Let’s start with the numbers: by the end of 2024, no other country had seen more people flee than Venezuela. According to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), 6.5 million Venezuelans are currently living in other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. Since the collapse in oil prices in 2014, Venezuela has experienced hyperinflation, shortages of food and medicine, a deterioration in healthcare and other public services and a massive rise in crime. At the same time, the increasingly authoritarian government has begun to crack down on opposition.

The situation is widely seen as one of the largest forced displacement crises in Latin America. No other country has taken in more displaced Venezuelans than Colombia. Millions of them have passed the border in search of protection. This makes Colombia the world’s third-largest host country for refugees.

In Colombia, the crisis has been exacerbated further by the influx of people fleeing other Latin American countries, many of whom are en route to the United States. Since the onset of the pandemic in 2020, the country has seen a general increase in transit migration from other South American countries such as Ecuador, from the Caribbean, Asia and even Africa. Almost 3 million international refugees currently reside in Colombia, adding to the challenges the country is already facing.

A role model for neighbouring countries

Nevertheless, Colombia has been better able to respond to the refugee and migrant crisis compared to other countries in the region. This is certainly due to the country’s own experience with displacement: Colombia has the third-highest number of internally displaced persons in the world. Despite the fact that the government and the FARC guerrilla group concluded a peace agreement in 2016, the decades-long armed conflict continues to this day. Clashes between armed groups lead to forced displacement, and by the end of 2024, around 7 million Colombians were registered as internally displaced persons.

The country’s institutional and administrative capacity to respond to the humanitarian needs of migrants and refugees stems from its efforts to provide protection to millions of its own citizens in recent decades. Colombia has spent years learning to adapt and respond to this societal challenge.

To address the Venezuelan exodus, Colombia implemented an interesting initiative in 2021. The Estatuto Temporal de Protección para Migrantes Venezolanos (Temporary Protection Status for Venezuelan Migrants – EPTV) allows Venezuelan migrants to legalise their status. It permits them to stay in Colombia for up to 10 years before having to apply for residency and provides a work permit, access to education and healthcare services. All Venezuelans who were already in the country – whether legally or illegally – and those who entered legally between February 2021 and May 2023 were eligible. They could apply for the EPTV and receive the Permiso por Protección Temporal (Special Stay Permit – PPT), a document similar to a residence permit. The PPT lets Venezuelans approach local and regional governments to access various support programmes.

While imperfect, the EPTV allowed Venezuelans to try to rebuild their lives in Colombia and to integrate in the social-protection network of the country. According to estimates by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), Venezuelan migrants and refugees contributed $ 529.1 million to Colombia’s economy in 2022, accounting for almost two percent of the country’s total tax revenue. The IOM projects that as a result of the EPTV initiative, Venezuelans will contribute even more in the coming years.

Other refugees are less protected

When it comes to the EPTV, Colombia is an example for the continent. However, decrees and laws always also create necessary yet arbitrary limits to plans and programmes. Anyone who does not fall into the above mentioned categories is in limbo. This includes all people from other countries than Venezuela looking for shelter in Colombia. Most of them need to be recognised as “refugees” in order to acquire legal status. But Colombia has a stringent definition of what it means to be a refugee, which makes it harder to be recognised as such within Colombian institutions. Refugees are generally less protected and have consistently had less access to healthcare, education and work.

Being a migrant or refugee in Colombia poses many challenges, even for Venezuelans. Not only are many still struggling to regularise their status and access essential services. Migrants and refugees are often being stigmatised by society. They are being erroneously blamed for a rise in crime and seen as less employable, lazy and less deserving of support. In a country with high levels of informal employment and high precariousness, they are competing with locals for state support.

What’s more, Colombia is a country that is still dealing with several ongoing armed conflicts and currently observing a worrying upswing in violence. Migrants and refugees living in Colombia are being increasingly impacted by violence and displacement and are at a higher risk of being exploited by mafias and armed groups. Reports illustrate the violence that occurs on migration routes from Latin America to the USA, which mafias essentially control. Refugees and migrants can be used by armed groups or find themselves caught in the crossfire. Colombia is no exception.

The USA and its gunboat diplomacy

Another reason why Colombia has responded to the refugee crisis so well is that it has the political will to do so. Historically, Colombia has been a right-leaning country, and given its leadership’s distaste for the Venezuelan regime, it has welcomed Venezuelan migrants with sympathy.

More recently, however, the government of Gustavo Petro has struck a different tone. Petro, who took office in 2022 as the first left-leaning president in Colombian history, has worked to ease tensions with Venezuela. This shift in position has led to a reduction in support for the programmes that assist migrants and refugees, which is coming on top of cuts to USAID funding for humanitarian programmes. In the end, the protection of migrants and refugees also depends on the state of international affairs.

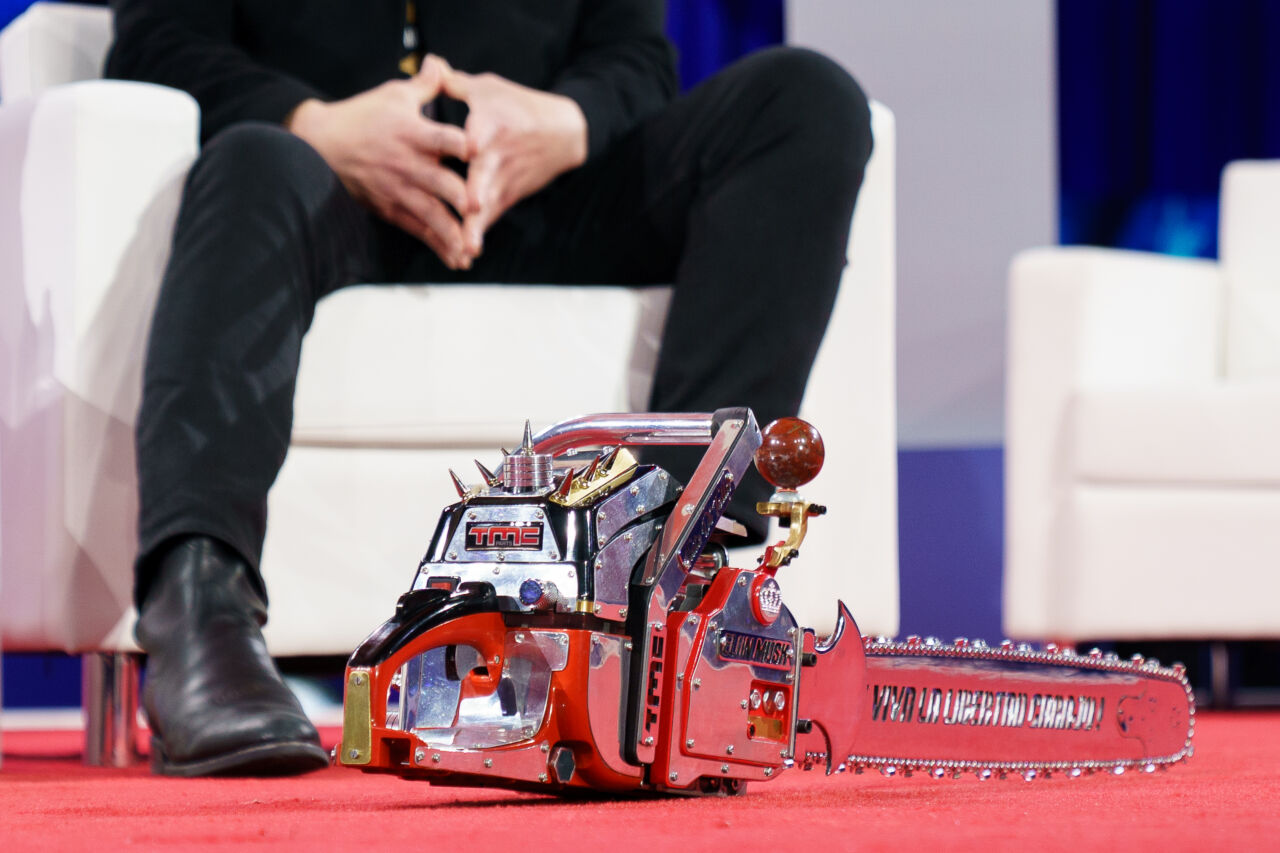

The USA has recently deployed naval ships around Venezuela as part of its gunboat diplomacy and continues to clamp down on migrants and refugees. It remains to be seen whether these tensions will increase the outflow of Venezuelans searching for shelter. It’s possible, too, that migrants and refugees who were trying to reach the USA will now break off their journey. This will present Colombia with future challenges in fulfilling its humanitarian duties. For now, however, it can be said that despite its past and present difficulties, Colombia has chosen to defend humanity.

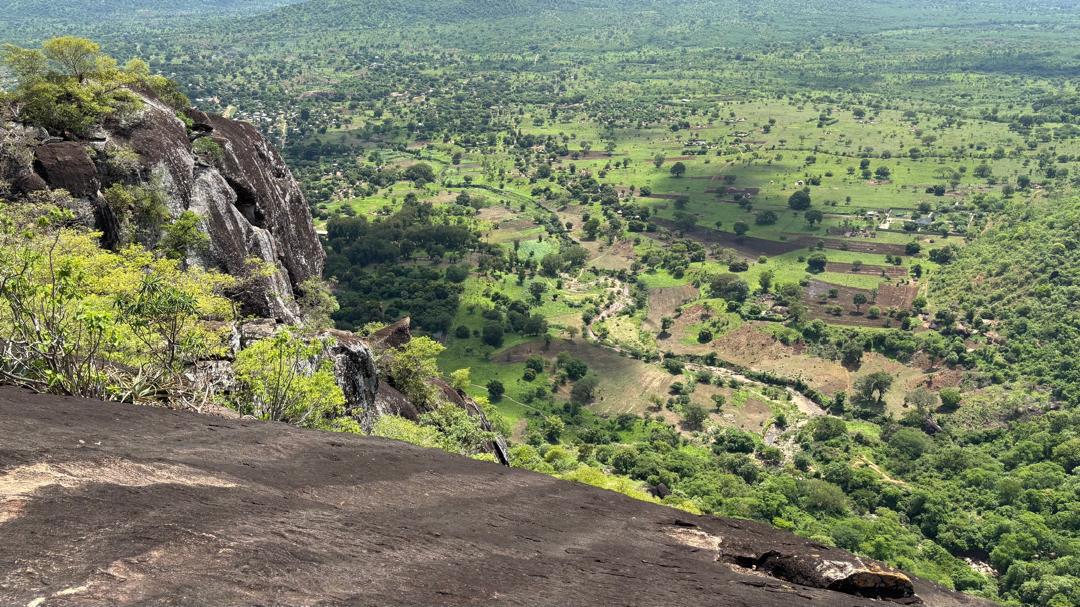

Fabio Andrés Díaz Pabón is a research fellow on Sustainable Development and the African Agenda 2063, hosted by the African Centre of Excellence for Inequality Research (ACEIR) of the University of Cape Town, and a Honorary Research Associate at the Department of Political and International Studies at Rhodes University.

fabioandres.diazpabon@uct.ac.za