Early childhood development

Various potentials

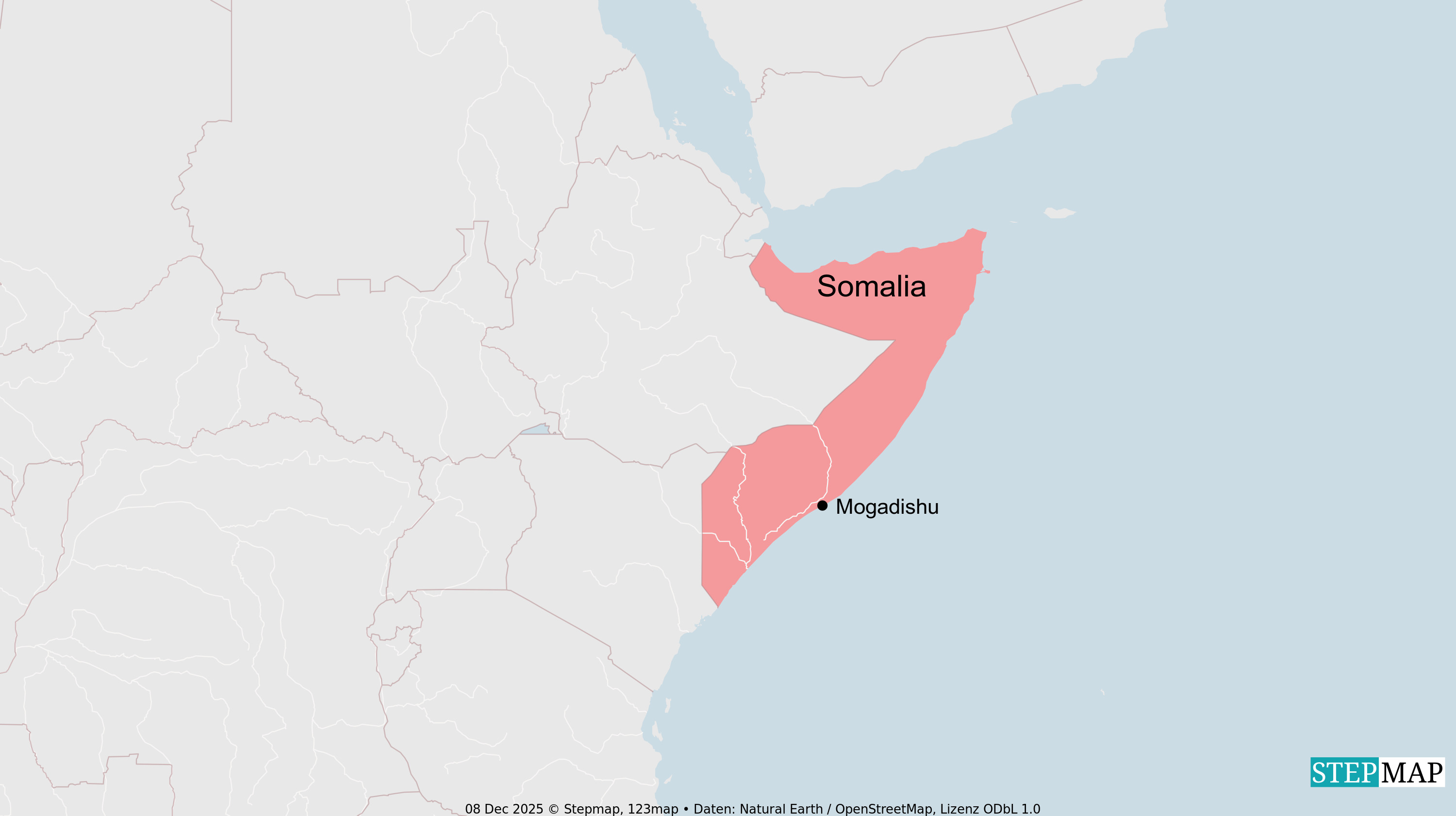

Early childhood development, particularly caregivers’ responses to its different stages, varies considerably around the world. During our research in a village in rural Kenya, we found two-year-old Kibet sitting alone on a tree stump, whimpering fiercely and kicking his feet; his face was a picture of rage and misery. His mother, who was busy chopping wood for the cooking fire in the house nearby, had a simple explanation for her child’s tantrum: “Kasinyin” – literally “his work”. She explained that he was just “doing his thing” and that he would soon get over it on his own. Such examples of self-assertion – whether charming or annoying to caregivers – mark the increasing autonomy and ability to think about oneself in relation to others that characterises early childhood development. However, how caregivers react to this varies from society to society.

At the same time, a child’s evolving abilities give rise to new expectations and demands within their “developmental niche”, the culturally structured environment of daily life. These expectations, which often take the form of “developmental timetables”, reflect the beliefs held by parents and caregivers regarding the ages at which children should acquire specific developmental skills.

For example, a study of grandmothers’ developmental expectations for children aged three to five in Botswana by Marea Tsamaase looked at the skills required for self-care, communication, learning Setswana customs and taking on household chores. Grandmothers expected three-year-old children to be able to dress themselves (without putting on clothes backwards), eat independently and, most importantly, follow simple commands. By the age of five, the grandmothers expected the children to be able to do some of their own laundry and help with the cooking. The word “clever” (“botlhale”) used by these grandmothers was closely related to social skills and reflected the child’s ability to carry out household tasks and other valued skills, such as bringing a chair for a visitor.

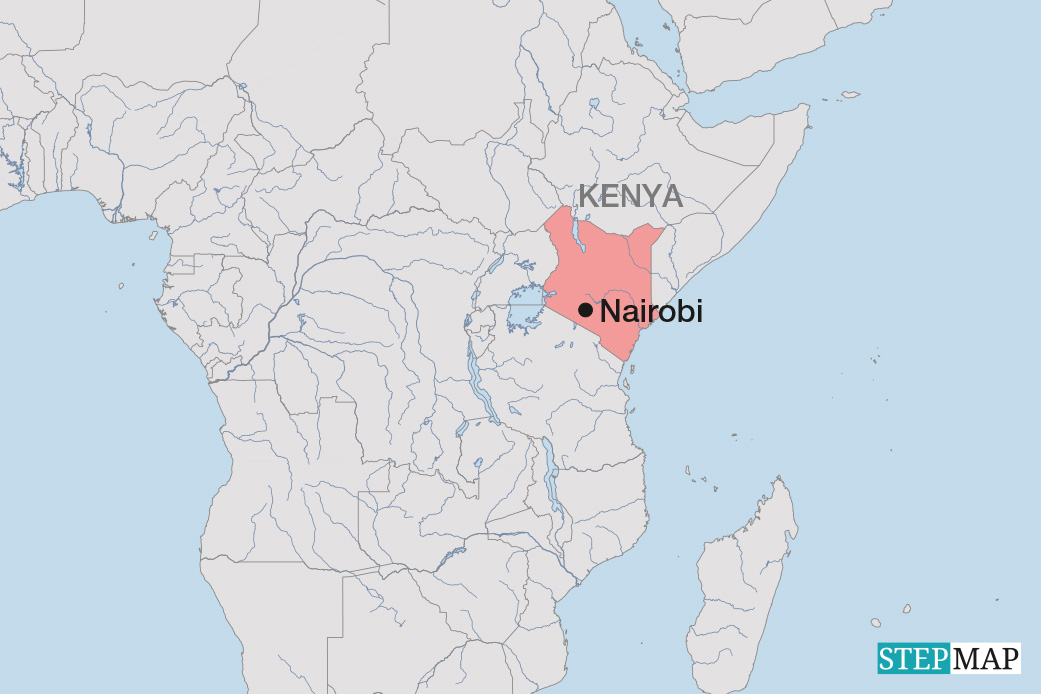

The cultural model of intelligence as socially embedded has been identified in various sub-Saharan communities. Among the Kipsigis in western Kenya, for example, children’s “intelligence” was often judged by their ability to do housework without supervision. Similar observations have been made in Côte d’Ivoire, Zambia and Nigeria. The immediate goal is to have a child who can be relied upon from an early age to take on a variety of responsible household tasks, including caring for younger siblings.

In western societies too, culturally rooted developmental plans have a significant impact on the acquisition of different skills at certain ages and influence parents, teachers and policymakers. A collaborative study of parents and preschools in Italy, Spain, the Netherlands and the US found that while there are similar agendas for early childhood education, the underlying goals for children’s development vary.

In Italy, almost all children start preschool at the age of three and attend until the age of five. Children in preschool participate in planned activities such as games, expressive or motor activities, in addition to lunch, a nap and an afternoon snack. Pre-academic activities are introduced in the last year of preschool, but more emphasis is placed on respecting rules, such as raising the hand before speaking and staying seated during structured activities. Targeted pre-graphic exercises may be introduced for literacy acquisition, as well as phonological exercises to begin learning the alphabet and exercises on quantities to support the development of number learning.

Early childhood education in the Netherlands is structured somewhat differently, as general pre-school education begins at the child’s fourth birthday and is integrated into primary schools; however, the content of Dutch pre-school education is quite similar to the Italian system.

School-related skills paramount

In contrast to early childhood education in western Europe, three- and four-year-old children in the US are cared for in a variety of ways, such as at home with family or a babysitter, or in a centre-based daycare or preschool. In recent years, there has been increasing pressure on educators and parents in the US to accelerate the acquisition of school-related skills. As one daycare teacher in Connecticut told us during our research, “we are now teaching preschoolers what used to be taught in second grade.” Accordingly, we found clear trends in parents’ perceptions of their own role in teaching school-related skills to young children before the children actually enter formal education: Nearly three-quarters of US parents indicated that they believe it is important to teach their children such skills.

Concern in the US about preparing children for school at an ever-younger age has been fueled in recent years by media attention to the importance of “brain development” in the first two or three years of life, which is said to require intensive educational intervention before a child’s chances of reaching its full potential are irretrievably lost.

Ironically, the goal of helping children “reach their full potential” emphasised in international publications such as “Nurturing Care for Early Childhood Development” by UNICEF, the World Health Organization and the World Bank, neglects the wide range of skills necessary for successful development in different cultural contexts. Instead, it recommends that parents follow current western middle-class practices aimed at early academic development and autonomy.

Link

Harkness, S., Super, C. M., Bonichini, S., Ríos Bermúdez, M., Mavridis, C., van Schaik, S. D. M., Tomkunas, A., & Palacios, J. (2020). Parents, preschools, and the developmental niches of young children: A study in four western cultures. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 170, 113-142.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cad.20343.

Sara Harkness is a social anthropologist who has studied children and families worldwide.

sara.harkness@uconn.edu

Charles M. Super is a developmental psychologist whose research focus is the unfolding of early development in diverse human cultures.

charles.super@uconn.edu