Global governance

Climate refugees

“For most questions, we don’t have a consensus,” says Walter Kälin of the Nansen Initiative, a Norwegian-Swiss outfit. It was established in 2012 with the mission of jumpstarting international dialogue on a coherent and consistent approach to protecting people displaced by the impacts of climate change.

Kälin points out that different sets of rules apply to different refugees. Those who leave their countries are basically protected by human rights law, but refugee law applies only to a very limited extent. For internal refugees, there are the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement and African Union Convention for the Prevention of Internal Displacement and the Protection of and Assistance to IDPs (internally displaced persons) in Africa.

So far, most climate migration is internal, says Koko Warner of the United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security in Bonn. In the future, she expects disasters to cause more cross-border migration however.

According to her, the questions most people ask about global warming are: “How will it affect us? Can we adjust?” Households with money, political influence and protection by various institutions are resilient, she says. If need be, they can plan migration. For poor people, however, moving tends to be one of last options. The reason is that their livelihoods depend on their immediate environment. Warner argues that they are the most vulnerable to climate change, and the least likely to migrate in an organised and pre-meditated manner.

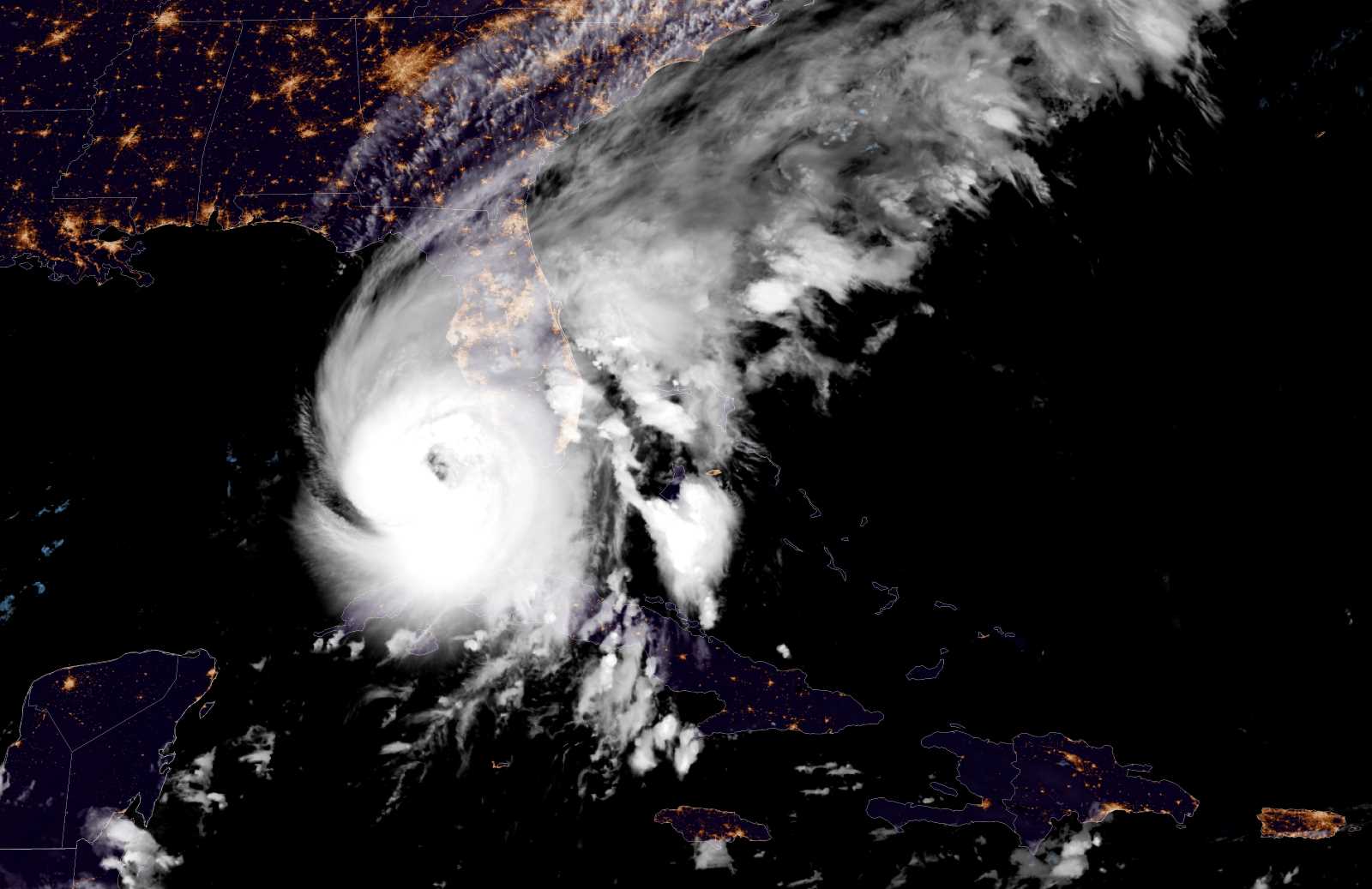

One of the great challenges in the debate on “climate refugees” is whether people are really fleeing because of global warming. Slow-onset disasters, such as the rising sea level which will flood small islands and low-lying coastal lands, are relatively easy to link to climate change. But sudden-onset disasters, such as Hurricane Sandy that recently swept Caribbean islands and the north east coast of the USA in October are harder to link directly to global warming.

Since 2008, however, a broad consensus seems to be emerging that global warming is indeed leading to disasters, both sudden and slow, says Jose Riera of the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR). In his view, climate change is multiplying existing threats: “Seasons are becoming less predictable, as is rainfall. This has repercussions for food security and mobility.”

At a conference held by the United Nations Association of Germany in Berlin in January, Riera suggested working pre-emptively on solutions. Relevant questions, according to him, include: “How can states plan and provide for migration – especially internally? And if people are forced to migrate, how can we ensure that human rights are respected?” The great challenge, in his eyes, is to “prevent the most vulnerable people from becoming trapped by circumstance!”

Experts agree that there will be no multilateral agreement on these matters soon. Annette Windmeisser of Germany’s Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) says: “In the near term, a global solution is illusory.” But national and regional solutions are possible, she insists, pointing to insurance programmes, early warning systems or preventive measures like building dikes.

In a recent German-language publication, an alliance of non-governmental organisations acknowledges that it is difficult to define the appropriate terms and draft the agreements needed to tackle the challenges of climate flight. They insist, however, that such challenges “must not lead to a delay in finding solutions”. Among other things, they want governments to handle migration issues more liberally in view of the mounting problems.

Ellen Thalman

Link:

Amnesty International Deutschland, Brot für die Welt, UN Association of Germany (DGVN), Germanwatch, medico international, Oxfam Deutschland, Pro Asyl: “Auf der Flucht vor dem Klima” (Fleeing the climate, only in German)

http://germanwatch.org/de/6245