Segregation

Revisiting South Africa’s segregationist past

In 1948, the National Party won a whites-only election. It represented the interests of Afrikaners, the ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch settlers who saw their victory as a triumph over British colonists. The National Party subsequently implemented segregation with brutal efficiency, inflicting mass suffering on the black majority.

Black people were barred from many public places, could only visit city centres for work and were forced to settle in specific areas. Their access to law courts and public services was restricted. Trade unions were not forbidden, but apartheid laws meant they could not assertively fight for black workers’ rights. Mixed marriages were illegal.

For decades, economic growth was driven by the country’s rich natural resources, especially gold and diamonds. The mining industry exploited black labour, and its success allowed white South Africa to thrive. Nonetheless, pressure to change kept growing, both domestically and internationally.

The National Party’s grip on the country began to loosen when violent protests started in Soweto outside Johannesburg in 1976 and soon spread nationally. Subsequently, civil-society and faith-based organisations around the world called for boycotts of South African goods. In 1986, even the US Congress imposed economic sanctions.

The success of liberation movements in neighbouring countries such as in Mozambique, Angola and eventually Zimbabwe, moreover, meant that apartheid South Africa stood increasingly alone and it became obvious that its white conscript army was becoming overburdened.

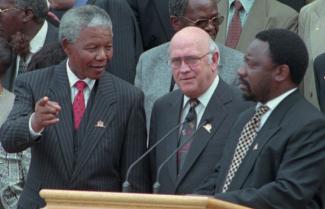

At the same time, repression of the black freedom movement in South Africa consistently led to yet more international opprobrium. Against this backdrop, the leadership of the National Party started negotiations with the ANC (African National Congress), initially in secret. President Frederik Willem De Klerk thought that an agreement with the ANC would preserve some protection and privilege for whites – and specifically for the Afrikaners as a group.

It did not turn out that way after De Klerk unbanned the ANC and the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA) started its work in 1990. In addition to the National Party and the ANC many anti-apartheid groups were involved in the Convention, but generally played second fiddle to the two dominant negotiating partners.

After long and intense deliberations, a liberal constitution was adopted. Its bill of rights protects individual, not group rights. In 1994, the first democratic elections put the ANC in power – where it has stayed ever since. Its track record is mixed (see main story).

Jakkie Cilliers is the founder and former executive director of the Institute for Security Studies, a non-profit organisation with offices in South Africa, Senegal, Ethiopia and Kenya.

jcilliers@issafrica.org