Internet

Digital childhood

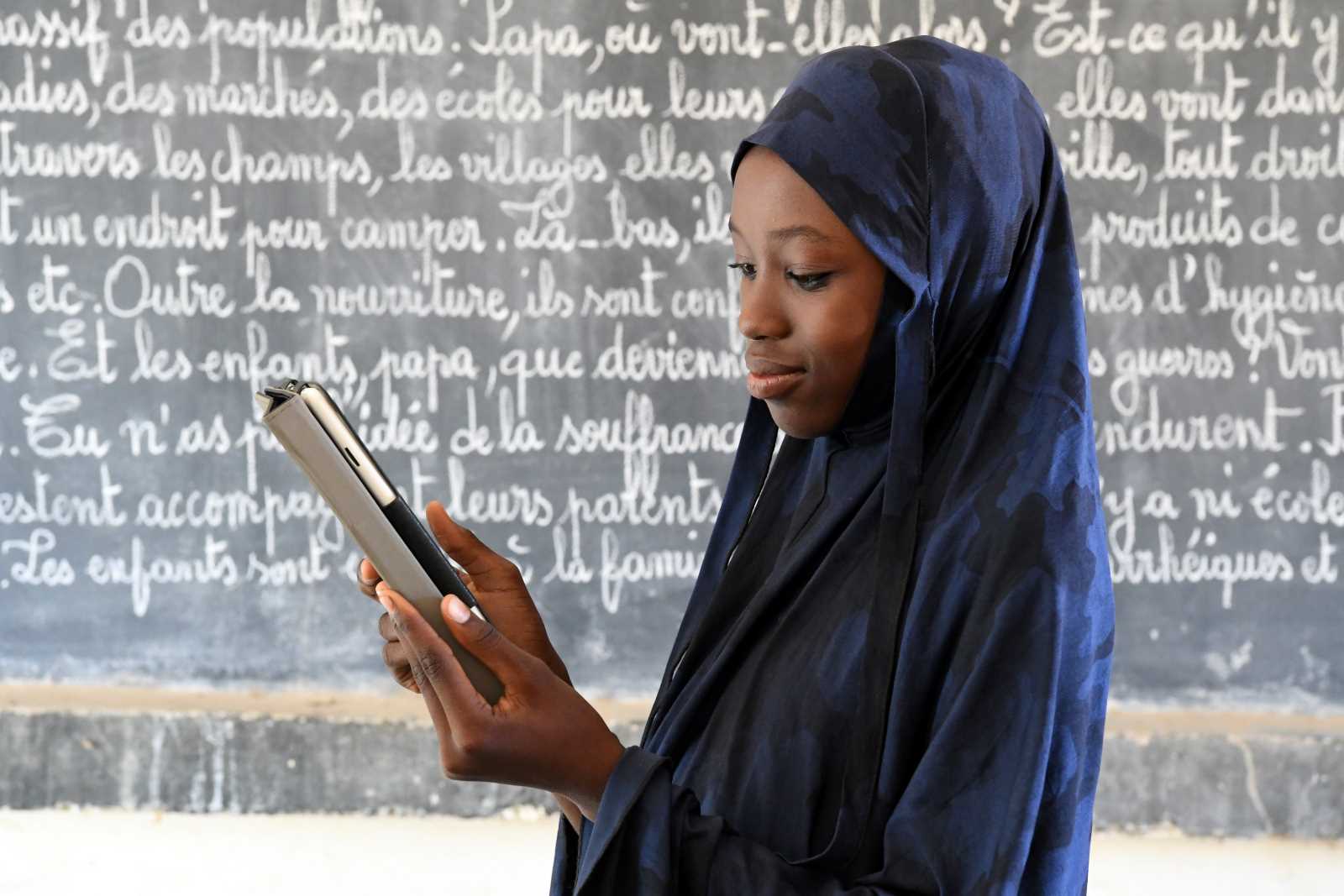

Digitalisation is increasing the tremendous opportunities the young generation has with which to engage the world. UNICEF’s “State of the World’s Children 2017” report points out that information and communication technologies (ICTs) are giving ever more people access to high-quality educational content, including textbooks, videos and remote instruction. The costs are low.

However, the proliferation of educational internet content cannot simply replace competent pedagogy in schools, the UNICEF report warns. Guidance and adult supervision are necessary. The internet is valuable for learning new things, but it is no substitute for the engagement with parents, teachers and other educators.

According to UNICEF, the internet contributes to bridging social divides. It makes information available to both genders, for example, and it is becoming accessible in ever more remote areas. In the developing world, it can serve professional and vocational training, offering new economic opportunities. As the authors write, young people with disabilities can benefit too, not least because they can find information and interact with others without having to leave their homes. Digital divides persist, however. Disadvantaged communities tend not to enjoy access to the web to the extent that better-off communities do. Connectivity infrastructure depends on private as well as public spending. Social disparities are further deepened if the latter is inadequate.

UNICEF outlines three kinds of risks:

- Content – are risks when a child is exposed to inappropriate and unwanted content, such as sexual, violent or racist imagery. Such content can be deeply disturbing and even traumatising.

- Contact – are risks when a child unknowingly participates in dangerous communication with predators seeking youths for commercial, sexual or political purposes.

- Conduct – are risks when children produce online materials that are harmful to other children such as racially charged statements or even sexual content that they create themselves (sexting for example).

Youths (aged 15 to 24) are the most well connected group in the world, according to UNICEF. About 71 % use the web compared with 48 % of the global population. Evidence indicates that children are accessing the internet at ever younger ages. Accordingly, the dangers of cyber bullying, cyber crimes (theft) and unwanted sexual experiences are growing. UNICEF states that children from poor families are especially at risk of being victimised online because they are very curious, but unaware of what rules apply to internet interaction, who their potential correspondents might be and how they might be abused. The UNICEF authors want educators to make children digitally literate so they can navigate the dangers. At the same time, they want content providers to limit existing risks.

Although the internet helps to bridge gender gaps, such gaps persist. In 2017, only 44 % of internet users were female around the world. In India, the share was a mere 29 %. Girls are affected by such cultural exclusion too. One result, according to the report, is that they cannot use the internet to fill knowledge gaps concerning sex or reproductive health. Such information matters to them, but it is not taught in schools or discussed in family circles.

African youths are the least connected in the world. Around 60 % cannot go online, according to UNICEF. The reasons are socio-economic limitations and cultural barriers, especially in the case of girls. In Europe, only four percent of the people aged five to 24 do not have internet access.

UNICEF notes another important divide. In 2016, just 10 languages made up the majority of websites, with English alone accounting for around 56 %. Accordingly, many children and youths who are daily online users cannot find much information in their own languages. Some African and Asian languages have no written form, and some governments do not report in indigenous languages.

Cyber bullying is a concern. It can affect children, youths and adults. People of all age groups are sharing intimate information with friends on social media – and to some extent with the world at large. The young generation in particular uses connectivity to either bolster existing friendships, or create new ones. Children connect with each other more than ever, yet have changed the platforms of communication from offline interactions to online interactions. According to UNICEF, people are more likely to be harassed if they are not part of the mainstream because of:

- their physical or mental condition,

- their cultural, ethnic, religious or political affiliation,

- their sexual orientation or

- their economic situation.

Harassment happens online and offline, but while societies have ways to deal with offline bullying, cyber harassment is a new phenomenon. Victims are more inclined to abuse alcohol and drugs, not regularly attend school and have lower self-esteem, UNICEF warns.

Protection of privacy

There is an ever increasing need to protect the privacy of children and youths in regard to not only cyber bullying but also sexual predators, traffickers and radical agitators. New online platforms increase the access online predators have to children. Crypto currencies and the growth of the deep web and the dark web facilitate criminal activity, including sexual exploitation. UNICEF demands that these areas of the web should be policed.

Parents around the world worry about their children spending too much time in front of a screen. Research on the matter is inconclusive, according to UNICEF. Online interaction connects children from all geographical backgrounds, yet it may also make them less present in their current locality. Too much screen time, moreover, might result in insufficient physical activity. However, in a 2010 study drawing on a survey of 200,000 adolescents aged 11 to 15 in Europe and North America, showed that children already tended to lead inactive lifestyles back then.

There is a growing divide between how children and adults use digitalisation to engage with one another. Children see connectivity as a way to break down communication barriers, while parents worry that screen time may hurt their mental well-being. Parental concerns should not be ignored, argues the UNICEF report, but parents should better understand what the platforms mean for their children. The more adept they are in engaging with their children, the better they will be able to protect them from harm.

Parents should also make their children aware of which companies dominate the internet. A handful of corporations (Facebook, Apple, Netflix and Google) influence what billions of people around the world do with their time.

The youngest generation is the most diverse generation in history, and is only a few clicks away from copious amounts of information and people. Today’s children and youths are digital natives and the internet has become their second home. UNICEF argues that prudent policies must ensure that the internet becomes a safe place for them. Relevant stakeholders include governments, UN agencies, pro-children organisations, development institutions, educators and parents. Important goals are:

- Provide affordable access to high-quality online resources to all children.

- Break cultural, social, and gender barriers.

- Protect children from harm.

- Support law enforcement.

- Safeguard children’s privacy, identities and reputation online.

- Teach digital literacy to keep children informed, engaged and safe.

- Develop ethical standards for business and technologies.

- Involve private-sector companies in advancing appropriate ethical standards and practices.

- Give children and young people a voice in the development of digital policies.

Drake Jamali is an intern at D+C/E+Z, sponsored by the Congress-Bundestag Youth Exchange (CBYX), a programme that invites 75 young Americans to work in Germany and 75 young Germans to do so in the USA.

drakejamali@gmail.com

Link

UNICEF, 2017: The state of the world’s children 2017: Children in a digital world.

https://www.unicef.org/sowc2017/