Frieden schaffen

Transitionsjustiz und Wiederaufbau nach Konflikten

INTRODUCTION

Countries recovering from civil crisis are often described as being in transition. ‘Transition’ covers the period of movement from an old legal order attacked or destroyed by civil or political crisis, to a new one of democratic governance as part of post-conflict recovery. The transition may be one from armed conflict to peace and reconstruction(Rwanda, Burundi, Sierra Leone, Mozambique, Liberia, Cote d’Ivoire); a political one from dictatorship to democracy (Nigeria, Ghana, Togo, Guinea); or a combination of both; or as in South Africa, a transition from Apartheid to majority rule. It may also involve a process by which a particular society seeks to investigate its past, and to face squarely a historical memory such as the Holocaust, slavery, or to seek to confront and correct historical injustices meted out to an indigenous community.[i] Whatever the circumstances may be, there is usually an existing situation of structural violence that has bred political/or civil conflict. Post-conflict reconstruction would then entail an effort to restore the broken society, take stock of the past, right past wrongs or historical injustices and determine how a future untainted by the problems of the past could be forged. Such transition period often presents difficult choices in deciding how to deal with the past in order not to compromise the gains of post-conflict recovery, and how to fashion out a better future based on new core values, including respect for human rights and respect for human dignity of every citizen.[ii]

“Transitional justice”, then, refers to a number of special arrangements and mechanisms that may be put in place to address the overhang of legal issues arising from the old order, such as whether or not to hold persons with responsibility for the crisis accountable.[iii] Such mechanisms may be in the form of special tribunals to try alleged perpetrators; reconciliation commissions with a mandate to offer a public platform for apologies and other strategies for making amends; and other truth seeking bodies charged with making recommendations for institutional reform to address the root causes of the civil crisis. It is also true that whenever ‘justice’ is qualified by another word, it invariably dilutes the purity of that commodity and is not ‘real justice’ at all. Be that as it may, there are occasions when ‘justice’ as we know it may not be available, or even possible. Like the two-faced Roman god Janus, transitional justice looks backwards to demand accountability, and forward at the same time to reconstruct the future.[iv]

The international community has set its face against impunity, and will not condone any situation in which perpetrators are granted blanket pardons.[v] Both the Sierra Leonean and Liberian Truth and Reconciliation Commissions were explicitly prohibited from granting amnesties for gross human rights violations and crimes against humanity.[vi] However such a posture does not address issues relating to whether compromising justice in favour of peace would be a necessary sacrifice that a society would have to make.[vii] Nor does it address the issue of whether there would be an enduring enough peace to permit reconstruction to proceed if there should be general apprehension among the populace that the future is not secure on account of those who harbour grievances of not having been well-served by the compromises. It is not every country that has used active transitional justice mechanisms during transitions. For instance, Mozambique and Spain ‘appear’ to have healed post-conflict wounds without resort either to truth commissions or to criminal trials. However, since a campaign for justice for victims of the Franco era has erupted in Spain after many years of silence, it is uncertain whether the comprehensive amnesty policy adopted post-Franco will hold. There are no straightforward answers to the question of whether violators of international humanitarian law should be prosecuted or pardoned – especially when they remain powerful enough to disrupt the social order.[viii]

This paper attempts to raise and expound on issues that face societies in transition as they seek to put the past to rest whilst keeping the demands of the post-conflict reconstruction in focus. The paper is in three parts. Part I discusses the concept of transitional justice, Part II zeroes in on truth commissions as a mechanism for achieving accountability and Part III is the conclusion.

I

Transitional justice immediately brings into focus issues pertaining to the past as well as to the future. It always takes place in a highly contested political space, and confronts questions that are critical to post-conflict recovery.[ix] Should perpetrators of gross human rights abuses such as genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes during the crisis be put beyond the reach of legal justice, or should they be made to face the rigors of the law?[x] What if that conduct was lawful at the time; or that there was no law prohibiting that conduct? As one author observes,

The war criminal will probably have risen to a position of power and responsibility in a state that was failing for reasons inherited from long ago and not of his or her creation, having imbibed philosophies and politics that forbad a real understanding of those other philosophies and politics that come with the intervention of outsiders who imposed a war crimes tribunal on the territory in which s/he tried to function.[xi]

Is there a minimum amount of “standard morality” that everyone should have? Should political exemptions or pardons be granted or should they be subjected to a process of retributive justice? Would compromises of principle have to be made in order to guarantee the peace? Would such compromises not amount to a denial of justice to victims? If they did, would that promote peace or would it deepen the culture of impunity which may have provoked the crisis to begin with? Other questions facing such a polity would be : should conquered leaders with blood on their hands be dealt with by political settlements and or by the law courts? Would insisting on prosecutions in those circumstances not do more harm than good?

For the international community, there may be issues of realpolitik to deal with, depending on the stage at which issues of accountability arise. For instance, should the international community insist on retributive justice to deal conclusively with impunity, would other warlords in the future be encouraged to lay down their arms and pursue political settlement if they knew they would be taken to the slaughter like sheep? Would leaders of other troubled polities not feel so vulnerable as to prolong the suffering of their people in order to secure control over state power that can serve as protection from accountability?[xii] Certainly Liberian Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), which finally brought peace to Liberia after fourteen years of civil war, would never have been signed had the possibility of prosecution been seen to be real at the time.[xiii] This belief is borne out by the fact that following the submission of the Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, recommendations to the effect that those who bore the greatest responsibility for the crisis should be tried by a court set up on the lines of the Special Court of Sierra Leone elicited a fierce public response from the former war-lords. Operating under the ambit of a newly-formed association of Signatories to the CPA, the former adversaries threatened to return to war if anyone laid hands on any of them to put them before a court. The fact this could happen about six years after the CPA had been signed, elections held and a democratic government put in office spoke volumes about what would have happened had the Agreement contained a provision on the prosecution of the war-lords, instead of a promise of a TRC. Certainly they believed at all material times, that they had been granted amnesty in recognition of their participation in the peace process, otherwise they may not have signed on to the CPA.[xiv] The move by the Kenyan Parliament to pass legislation withdrawing Kenya from the ICC after leaders who had been previously indicted won political power, suggests that nothing can protect one better than being in control of state power. If war lords fight tooth and nail to retain control over state power, then peace processes might be endangered. Clearly, then, when a society has a chance to achieve peace rather than a continued state of war, it would seem unreasonable to insist that there could be no amnesty, and so prolong the conflict.

However, while it might be thought that sweeping violations of international humanitarian law under the carpet might be better for assuring a peaceful societal transition, the reality does not bear this fact out. Experience teaches that there are wider costs to proceeding in such manner as to appear to condone impunity because,

…impunity challenges our notions of justice, peace and human security. It challenges justice because it ignores our duty to the victims. It challenges peace because it generates a sense of insecurity and grievance among victims that will be used to justify future outbreaks of violence and renewed cycle of retaliation and abuse.[xv]

Thus, tolerating impunity so that the powerful would have no fear of future consequences and future accountability, would not only remove any disincentive for leaders in other parts of the world, to refrain from perpetrating gross human rights violations or taking advantage of the vulnerable under similar circumstances; but would also make a recurrence of the conflict in that society unavoidable.

Justice? Whose Justice?

It has been argued time and again that there can be no peace without justice.[xvi] For this reason, societies in transition face a constant challenge of whether to prioritise the sustenance of peace or to meet the expectations of those clamouring for the punishment of those who caused the emergency or who used the situation to victimise others.[xvii] It must be clear that options are often dictated by whether or not there was a clear winner in the conflict or whether there was none. Where a ‘victor’s justice’ is possible because of an imposed peace by a strong external power, or because one side clearly lost power and influence, retributive forms of justice such as criminal trials and punishment are possible, and are preferred by those who are in power. However, where there is an arranged or negotiated peace, with the former leaders still powerful even if they no longer control state power, the situation becomes more complex. For instance, in Liberia, although most people appeared to believe that the “war lords” should be punished for what they did to civilian population, there was no such unanimity of thought as to who qualified under this rubric of the “war lord” who deserved to be punished. As the average individual’s definition of “war lord” tended to exclude their own “war hero”, no one could be restricted to the “war lord” category. The evidence on the ground volubly attested to this. For instance, Prince Yomi Johnson, a former war-lord who was notorious for his exploits during the civil war, had won a seat in the Senate to represent Nimba County, his county of origin, in the legislative elections of 2005. Though subsequently cited for gross human rights violations and recommended for prosecution by the TRC in 2010, he was permitted to run for president in the 2011 presidential elections, the recommendation for prosecution notwithstanding. He won so massively in Nimba County, that placed third in the returns, thereby becoming a power-broker whose endorsement was required to settle issues in the constitutionally mandated run-off elections held when neither of the two leading candidates secured enough votes to win the elections conclusively. The elections were eventually won by the incumbent president in November 2011, most likely in response to his active canvassing for votes for the president, in his home county . Could such a powerful figure have been prosecuted at the end of the civil war in 2003, without unravelling the peace?

Again, many persons caught in the web of such crimes believed at all material times that they were serving their people’s interests. The English poet Robert Browning captures this sentiment most vividly in his poem, 'The Patriot', which describes the feelings of an ex revolutionary of one of the 1848 revolutions in Europe who found that the very people who had thrown roses his way the previous year had hurried to the Village Square in order to get a "ringside" view of his execution as a traitor when the revolutions were crushed in 1849. In the cases involving Serbian leaders, witness the demonstrations that occurred upon their arrest, and determine whether the actors were wrong in believing they were serving their people. This is the reality of the choices societies in transition have to make when the former leaders still retain the capacity to mount a resistance that would upset the peace.

It is said that experience in several post-conflict societies has shown that, where perpetrators of grave human rights crimes are not prosecuted for any number of reasons, old wounds are speedily reopened, and social tension is rapidly ignited by innocuous events, leaving the society constantly on tenterhooks. Indeed, twenty years after he had left office, legal processes were begun in UK, Spain and Chile to attempt to bring Chilean President Augusto Pinochet to justice for massive human rights violations committed by the government he headed. The polarization of domestic public opinion that accompanied Pinochet’s eventual return to Chile is more than proof that whatever the option chosen after a major crisis involving the entire society, not all interests would be satisfied.

Choosing to prosecute perpetrators has its attractions. At a minimum, it reinforces individual accountability as its emphasis on punishment ensures that those who have inflicted suffering on others are also subjected to suffering in their turn. However, there are a number of practical difficulties with choosing prosecution. For instance, where, there have been mass atrocities as happened in Rwanda, Sierra Leone or Liberia, one has to accept the reality that prosecuting everyone involved would be impossible. Indeed, in Rwanda, the sheer number of accused persons threatened the stability of the justice system and threw doubt on the integrity of the formal justice system. In the end, a more culturally acceptable, though less satisfactory in terms of respect for due process, option to the formal court system, the Gacaca court, was resorted to, in order to move the case load and relieve the formal system of the strain and impossible stress it had been put under, by the effort to prosecute all perpetrators.[xviii] The rationale for resorting to such a mechanism was put succinctly by one scholar thus: “a mass plebeian process of justice [was] appropriate for the kind of mass crime committed … No perpetrator should be exonerated for his or her choice to participate in the genocide”. [xix]

Another difficulty may be that the courts themselves may have been destroyed by a prolonged conflict. Thus restoring it to functional capability may involve such time and expense that it might not be in a position to take on such a major task for many years. Where the courts have not been destroyed, the integrity and moral standing of the judges may have been so compromised by events of the conflict that they might have become complicit to the atrocities that occurred. It might thus be impossible to expect any form of neutrality from the judges, without which the judicial function cannot be performed with any degree of credibility. These formal aspects notwithstanding, the requirements for discharging the burden of proof might be too much for any prosecution,. The effect of acquittal on the public psyche, after the acquittal of known perpetrators, would be detrimental to any prospect of healing for victims of those atrocities. Therefore, those seeking to subject persons of influence, both social and political, to justice might very well have to redefine the nature of ‘justice’, or else postpone the endeavour until many years of peace consolidation have elapsed, in order not to unravel the peace.

What, then, would be the best option for a particular community contemplating avenues for righting past wrongs and settling the account in order to move into the future? The answer is: whatever would let the peace be sustained until the society’s capacity for managing internal differences and fierce controversy can be better handled. In other words, such societies need a reasonable period of peace consolidation in order to restore its social elasticity and absorptive capacity to deal with internal wrangling without imploding. For instance, thirty years after the Nigerian civil war, the country moved from a point of a wilful suspension of memory to the establishment of a truth commission in 2001.[xx] Obviously, the ‘No victor, no vanquished’ declaration of President Yakubu Gowon did not erase hurtful memories. Nevertheless, it may well be that, for some societies, deferring the day of reckoning may facilitate a stronger ability to cope with the trauma of truth commissions (TC) or trials at a later date.

Deferring the day of accountability has sometimes been misconstrued as seeking peace at any price, without adequate attention to the need for justice. The debate as to whether there can be peace without justice, can be re-framed to the question whether there can be justice without peace? Clearly the prioritization of peace cannot mean underplaying the need for justice. It simply means redefining justice so that the two can move in tandem. Some have, indeed argued that the peace-versus-justice debate is hinged on a false dichotomy[xxi]

If a society is to redefine ‘justice’ then a basic question arises: “Is it to be retributive justice or restorative justice?”[xxii] Whose notions of justice should prevail – the victims’ or the perpetrators’? Further, “Who makes the choice on behalf of the people?” If not the leaders, then who? If it should be the leaders, would they not succumb to the temptation to cover up for their own kind? If it is not to be the leaders, then how would the generality of opinion be ascertained, and how would consensus be signified?[xxiii] In any case, would a society recovering from conflict be capable of achieving such consensus over an issue fraught with controversy? These questions, none of them easy to answer, plague societies in the aftermath of civil conflict.

It is a reality that often the decision is not a ‘choice’ strictly so-called, by the people, but an imposition by those who stepped in to bring the crisis to a close or those who won the war. Often the choice made may be a form of victor’s justice’ as the political leaders in office may have been the ones to face questions had the tables been turned. For instance, although the Nuremburg and Tokyo trials were intended to help the world and Germany close the chapter on the past, was that solution dictated by Germany or approved by the generality of Germans? In pleasing the international community, was any thought given to what the average citizen of the Axis countries wanted? In like manner, it is no surprise that when a choice has been made to use a restorative mechanism such as a TC, it is not usual for public consensus to be obtained. It should be no surprise that TCs seem to be more popular with international community than they are with local constituencies, who sometimes consider restorative justice as a slap on the wrist of perpetrators and a slap in the face of victims.

There are occasions when the choice is dictated simply by the availability of funding. The question of who would pay for the cost of bringing the former leaders to account, may often determine what kind of account would be asked of them. It is not unusual for the choice is made by those who can provide funding for whatever mechanism of accountability is favoured, or for the choice to be dictated by an absence of external funding. This invariably becomes an issue of international politics. Some great powers may not support retributive justice mechanism such as prosecution because of their national interest. [xxiv] For instance, the United States did not support the establishment of an international criminal tribunal for East Timor, or for its acknowledged protégé, Liberia. It does not appear that the harshness of the experience or the longevity of the crisis alone could explain the disparity in treatment., for although Sierra Leoneans endured a 10-year brutal war, they could not have suffered any more than Liberians who also endured a war of equally unmentionable atrocities, lasting about 14 years [xxv]

Although the UN has consistently set its face against the granting of amnesties regarding violations of international humanitarian law, the practical effect may be lost if there is no funding available to follow through with the process. Special tribunals are very costly to set up and expensive to maintain, especially if they must rely on the services of foreign professionals. Thus, without funding from the international community, it would be impossible to set up courts that would deliver justice according to standards of international justice, or detention facilities in which the accused persons would be housed for the duration of the trial, or custodial facilities within which sentences would be served in the event of convictions being secured. Countries recovering from conflict would hardly have the wherewithal to provide and support these expensive institutions. For instance, when the Liberian TRC made findings to the effect that some persons had a case to answer for atrocities committed, and duly recommended their prosecution by a special tribunal set up for the purpose, it became clear that the international community was not going to fund such a body. In the event, sovereignty norms of International Law have ensured that no move can be made in this direction without a request for support from the Government of Liberia. So, despite the strong recommendations of the TRC for the prosecution of perpetrators, it is unlikely to happen in this decade!

Looking at the past a development imperative?

A society that has had a fractious past cannot have a peaceful present. Where the conflict has developed over contested memories, such as memories of ethnic superiority or subordination, then it would be of great importance for the whole society to be provided with accurate information on their past in order "to bring to agreement or union"; the whole society. No one can deny the importance of accurate historical information, which often is unavailable because particular groups of power-brokers may have hi-jacked the nation's history at particular points in time and may have distorted events to paint a picture that is entirely false or unflattering of other groups. If accurate information on a nation's past is known, fashioning a future based on national unity is that much easier. At least the real price paid by some citizens in the history of the particular nation would be known, and the essence of those sacrifices better appreciated. Thus, straightening out the history of the country is an important endeavour if everyone is to be reconciled to the history of the country and to events as they really happened, and not as they were allowed to be recorded. This made it all the more strange when an Afghan Minister stoutly defended a decision to exclude happenings of the last 60 years so as to “bring the people together, and not to divide them. How were they going to be brought together if each side favoured a contested version of events that had occurred only sixty years earlier?[xxvi]

Policies of the past that have led to marginalization or non-inclusion of certain groups in governance, are also known barriers to state cohesion and sources of conflict and controversy. It is indeed the case that every country depends upon certain attitudes such as, the feeling of being well-protected, the sense of belonging, the trust that the state would afford assistance in times of difficulty and therefore a personal commitment to its preservation, ( or simply put, patriotism) of its entire citizenry. These sentiments are, indeed, the building blocks that determine the strength of its body politic, its unity, its peace and tranquillity and consequently its progress and development. It is, thus an equally obvious reality that no country can hope to enjoy any of these necessary sentiments of nationhood, if many of its citizens are unwilling or unable to peacefully co-exist on account of grudges that they bear towards it and towards one another by reason of injury and oppression suffered at the hands of those who were acting in its name at particular points in its history. One of the common characteristics of each of the “failed states” of Africa has been its inability to develop commitment and attachment of its citizens to its existence and preservation. Such inability, often occasioned by marginalization and/or non-inclusion, may have led many of its citizen to feel that they would be better off if they were not a part of that particular political entity. Therefore an opportunity to learn from the past can only be helpful to the future development of such a polity.

Another fact that must be highlighted is that the society itself has an interest in ensuring that the pain and destruction – both human and material - occasioned by civil conflict do not re-occur, hence the need to examine the past. However, many people oppose such introspection on account of the fear of being victimised by such effort, as the process is bound to engender some finger-pointing at the office-holders and other persons in authority at the time. They often feel, and rightly so, that they executed the desires of the public as articulated then, but events having made the public wiser after the fact, are now being held up as social pariahs for having done the very things for which the public had hailed them in times past. The legitimacy of these feelings must be acknowledged, and the public has to appreciate that the guilt for those events is not that of the “perpetrators” alone because some of those violations may have occurred because the public was either accepting of such conduct or even worse, actively cheered on the perpetrators. [xxvii] Consequently, the active development of strategies to prevent the creation of the kinds of environment that produced the events under review, as well as any reforms of existing institutions and structures necessary to avoid a repetition of those tragic events must continue to engage the attention of the nation, long after the transitional justice phase has ended.

II

MECHANISMS FOR ACHIEVING ACCOUNTABILITY

TRUTH COMMISSIONS

A TC is established basically to seek the truth about past events, chronicle accurate accounts of those events in a public manner and initiate processes intended to reconcile the society. There is no specific model for TC as its objects may vary, converge or diverge, and may require a combination of the establishment of the “truth” of certain historical events, some effort at reconciliation, some attempt at reparation, or some demand for criminal accountability.

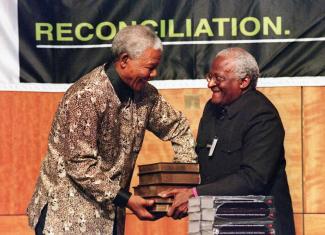

From the mid 1970s, truth and reconciliation commissions emerged as a middle ground between political exemptions from prosecutions and courtroom trials.[xxviii] Truth and Reconciliation Commissions (TRCs) as they were known worldwide, and now TCs have become the mode by which nations with a troubled past seek to come to terms with their past, and make amends for misdeeds done in the name of the state, to fellow citizens. This phenomenon was prominent in Latin America, but was popularised following South Africa’s transition from Apartheid to black majority rule. Since then, more than 30 countries have utilized combinations of truth commissions and amnesties to facilitate transitions towards stability.

This trend of resorting to up TCs has been set by developments in the field of human rights occasioned by the rise in Natural Law philosophies after WWII; the re-kindling of the philosophy of the Social Contract between citizens and the state; and the rise of democratization in Africa. This renewed appreciation of the responsibility of the state for all its citizens and the adoption of liberal democratic ideology of governance, have in turn created the opportunity for persons who suffered human rights abuses under authoritarian regimes to complain, and to demand reparation for whatever they suffered. Again the realisation that such hurts produce bitterness and negative feelings that can be passed on from generation to generation and thus have the capacity to undermine national cohesion and the eventual stability of the state, has in turn spawned a worldwide movement to demand justice for such victims from the state.

The modus operandi of a TC

A TC uses the model of public inquiry to encourage truth-telling about past event, with the hope that such truth would assist the society to come to terms with its past, and so foster reconciliation.[xxix]The institution has been criticized as being a “soft option born of political necessity [that avoids] an unequivocal attack on impunity.”[xxx] Capturing the essence of TCs, Alex Boraine,[xxxi]has explained that,

Documenting the truth about the past, restoring dignity to victims, and embarking on the process of reconciliation are vital elements of a just society. Equally important is the need to begin transforming institutions; institutional structures must not impede the commitment to consolidating democracy and establishing a culture of human rights.[xxxii]

If this is so, then why do people oppose its establishment? Apart from the reasons already proffered, much has to do with the word ‘reconciliation’ which is sometimes required of a TC. Does truth-telling truly foster reconciliation? Many have expressed doubt as to the veracity of this claim. However, what is not in doubt is that no one has ever built a secure future on lies and “official truths.”[xxxiii]

The word "reconciliation" is subject to a number of interpretations, all of which are applicable to TCs at one and the same time. "Reconciliation" according to the Chambers' Dictionary has any of the following meanings (1)"to restore or bring back to friendship or union"(2) "to bring to agreement or union"; (3) "to pacify"; (4) "to make, or prove consistent"; (5) "to adjust or compose", etc.[xxxiv] All these possible meanings of the word "reconciliation", carry their own baggage of connotations. Thus, whichever imagery 'reconciliation' evokes in a particular mind serves as the basis for the person to accept or reject the necessity, importance and relevance of a TRC. For instance, where the meaning attributed to the word is either (1) "to restore or bring back to friendship or union" or (2) "to bring to agreement or union", then the only images evoked are those of "two former adversaries suddenly dropping their animosities and shaking hands in friendship". This unreal image casts doubt on the probability of such an event ever occurring as a result of the process – particularly when the powerful perpetrators are still breathing fire and are showing no sense of wrongdoing. In much the same vein, images of reconciliation as an effort "to pacify" immediately evoke images of persons whose wrath may have been re-awakened by re-living past trauma, going on a rampage due to an inability to appropriately pacify them, thereby disturbing a hard-won but fragile peace. The truth of these criticisms notwithstanding, it is clear that much of the confusion comes from not distinguishing personal reconciliation from national or political reconciliation.[xxxv]

Strengths and Weaknesses

Like every human institution, the TC mechanism has its strengths and weaknesses:

1. TCs focus on victims and seek restorative justice. When a perpetrator confesses his crimes, the victim is empowered and thus restored in a psychological sense. This avoids adversarial processes that pit the victim against the perpetrator

2. They can have a healing effect on the wider society because they are more accessible to ordinary citizens than the courts; and the public airing of crimes, engenders a greater degree of public participation than criminal trials.

3. The amnesties offered by truth and reconciliation commissions encourage a greater willingness by persons involved in the events in question to participate in the process. In so doing, they tend to yield a far more complete narrative of events.

4. TCs are better for truth-finding about past events than prosecutions for criminal trials. Criminal trials focus on one individual at a time; are rigidly controlled by rules of procedure which restrict the ability to engage in wider social inquiry than the particular case allows; and require such a high standard of proof that the standard required becomes a limitation on the ability to establish the truth about past events.

5. They facilitate reconciliation more effectively than prosecutions, and criminal trials may hinder rather than help reconciliation.[xxxvi]

Despite these acknowledged strengths, TCs have significant weaknesses. The debate between impunity and accountability is re-ignited, as many believe that a resort to a TC is a copping out and amounts to “skirting accountability.”[xxxvii]

Perhaps is because the nature of a TC is not properly appreciated, leading to the raising of hopes and aspirations it is not configured to meet; TCs promise more than they can deliver. As Priscilla Hayner has observed,

“… the expectations for truth commissions are almost always greater than what these bodies can reasonably hope to achieve. These hopes may be for rabid reconciliation, significant reparations to all victims, a full resolution of many individual cases, or for a process that results in accountability for perpetrators and significant institutional reform. Due to a variety of reasons … few of these expectations can be fulfilled by most truth commissions.” [xxxviii]

Thus, since they are unable to ensure or enforce accountability for mass atrocities, they do not assuage the thirst for revenge and the hope of achieving it one day, that victims consistently nurse and nurture. The process thus leaves victims with a hangover that makes it difficult for them to heal. Yet, far from this being legitimate criticism, an examination of the argument shows that it is built more on the occasions when amnesties have been granted without any truth-seeking effort, than after such effort, and so cannot be adjudged a fair criticism. In this regard it is the fate of societies that opted for blanket amnesties, such as Nigeria in 1970, that are more instructive.

Apart from the difficulty of getting powerful perpetrators to participate in TC hearings, or showing contriteness to the victims, there are other practical and philosophical bottlenecks. If, as the process requires, forgiveness by the victim is cardinal to the initiation of a reconciliation process, then there are issues such as: Who can forgive, and for what wrongs? Can the living forgive on behalf of the dead? Can a President, who did not participate in the commission of atrocities apologise on behalf of everyone, including perpetrators who refuse to show remorse?[xxxix] Can forgiveness occur without remorse by the perpetrator?[xl] What then would be the nature of this “general apology”? Would such an apology be real or merely symbolic? If symbolic, would it be acceptable to the victims? The converse can also be problematic: If wrongdoers should apologise, can the President forgive them on behalf of the victims who may all have died?

LUSTRATION

One mechanism that is often used as a penalty against office holders who supervise gross human rights abuses is to bar them from public office permanently, or for a specified period. Popular with ordinary people, it inevitably comes up against a number of criticisms 1) there is a lack of due process in imposing such a major penalty without a trial that enables the accused person to mount a defence; and (2) it smacks of a mechanism for depriving political opponents of the opportunity to compete for power or public office.[xli] The legitimacy of those criticisms cannot be questioned, yet lustrations have on occasion assuaged the angst of victims when their perpetrators are deprived of the opportunity to ever use state power again to abuse the rights of citizens.

PAYMENT OF REPARATIONS

Reparations have been classed under outcomes of TCs for so long, that their stand alone stature has hardly been recognized. Yet paying reparations has existed longer than TCs, and has for much longer been the means by which past wrongs have be righted, or historical injustices dealt with. The war reparations that used to be exacted from a conquered people has by and large given way to payments to individuals who are proved to have been the victims of some atrocities. Such reparations serve a useful purpose in giving victims an assurance that their pain has been acknowledged, thereby bringing them closure. Care must however be taken in not making reparations seem as if the payment is blood-money, because then the victim would have been victimized twice.

MEMORIALS AND MEMORIALISING

Memorialising may take many forms, including the building of monuments and other memorials after traumatic events in the life of a polity. This manner of keeping such event in the eye of the public and in the public memory, serves a number of purposes all of which have been recognized as being akin to mechanisms of transitional justice. Compelling the public to remember, is deemed to be one certain way of ensuring that such an event would never be repeated. According to Louis Bickford, memorials,

… reveal and make visible the names, stories and sometimes faces of victims; and force societies by the processes of conceiving of and developing memorials, by commissioning and designing them, and by their very presence, to look inward and critically examine happened at a horrible time and why.[xlii]

What is chosen to be memorialized and what is built as a memorial can both be productive of conflict and controversy. However, the very nature of fierce public debate may be cathartic for the society, particularly if the event involved mass participation and the lowering of standards of morality and compassion by the society as a whole.

III

CONCLUSION

In this paper, difficult questions that societies in transition often have to face in deciding how to deal with the past in order not to compromise the future, have been raised. The consequences of each answer to the future stability of that community have also highlighted, to the end that such societies might be assisted by the experiences of societies previously similarly situated. One of the major questions transitional societies have to deal with, in particular, whether or not retributive justice should be pursued, or whether emphasis should be on restorative justice to promote national healing and reconciliation is not an easy one to answer. If retributive justice is to be pursued, then further issues arise relating to what institutional structures be put in place for such trials would such trials to take place. Would there be a reliance on the old court system for prosecutions, when the courts themselves may have been compromised in the conflict or may have been weakened by the exodus of trained personnel during the civil crisis? If the old courts cannot be used, must new courts be set up? If local courts are unsuitable for the magnitude of offences committed would the international community be willing to support the setting up of international tribunals? If the international community will not provide such funding, can the country’s resources be applied to pay compensation of expensive internationals at the expense of restoration of basic services to aid recovery?

On another level, should the prosecution of violators of international humanitarian law be so prioritized as to supersede the society’s interest in maintaining the peace, especially when the personalities involved remain powerful enough to upset the newly-won peace? These questions do not admit of easy answers, but can neither be avoided nor evaded.

Beginning with the concept of transitional justice, the merits of truth commissions as a mechanism for achieving accountability as well as lesser known mechanisms such as lustration have featured in the ensuing discussion. All this is done in the hope that when a community must choose the best mode for itself, the options available would all be on the table, so that choices could be made bearing in mind that the society’s best interests dictate an acknowledgement of the past, as well as an appreciation of the fact that the future must be made free of the shadows of the past.

NOTES

[i] Priscilla B. Hayner, Unspeakable Truths. Confronting state terror and atrocity. Routledge, New York and London, 2001. chpt 2; Commissioning the Past: Understanding South Africa’s Truth Reconciliation Commission, Deborah Posel and Graeme Simpson (eds), University of Witwatersrand Press, Johannesburg, 2002.

[ii] Rev. Bongai Finca, “Retributive or Restorative Justice – Complementary or contradictory?” in Transitional justice and human security, Alex Boraine & Sue Valentine (eds) International Center for Transitional Justice, Cape Town, 2006, p.56 at 58-64.

[iii] Neil J Kritz Transitional Justice: How Emerging Democracies Reckon with Former Regimes, Vol II: Country Studies. United States Institute of Peace, 1995. Abdul Tejan-Cole, “Painful Peace - Amnesty under the Lome Peace Accord in Sierra Leone” Law, Development and Democracy, Vol. 2. 1999, p. 239.

[iv] Alex Boraine, AJ. Levy and R. Scheffer, Dealing with the Past: Truth and Reconciliation in South Africa, Cape Town, IDASA, 1994.

[v]Art 6(5) of 1977 II Protocol to Geneva Convention prohibits blanket amnesties to perpetrators.

[vi] The Special Court for Sierra Leone was barred from recognizing amnesties granted for the commission of crimes against humanity and other international crimes under Article 10 of its Statute which provided as follows:

“An amnesty granted to any person falling within the jurisdiction of the Special court in respect of the crimes referred to in articles 2 to 4 of the present Statute shall not be a bar to prosecution.” The crimes referred to are crimes against humanity, Violations of article 3 common to the Geneva Conventions and of Additional Protocol II, and Other serious violations of international humanitarian law”.

The TRC Act of Liberia has a provision with like effect when it specifically prohibited the TRC from granting amnesties to those guilty of gross human rights abuses and crimes against humanity.

[vii] Nigel Biggar, “Making Peace or Doing Justice: Must We Choose?” in Nigel Biggar (ed) Burying the Past: Making Peace and Doing Justice After conflict. Georgetown University Press, Washington DC, 2001.

[viii] Peacebuilding In Post-Cold War Africa: Problems, Progress, And Prospects. Centre For Conflict Resolution, Cape Town, South Africa, Policy Seminar Report, 2009 Number 33 p.50.

[ix] Atudiwe P. Atupare, “The Taxonomy of Transitional Justice in Africa: A reflection on the Theoretical Trajectories of Truth Commissions and International Criminal Courts.” (2011-2012) XXV University of Ghana Law Journal.p.1.

[x] Neil Kritz, “Coming to Terms with Atrocities: A Review of Accountability Mechanisms for Mass Violations of Human Rights”, (1996)59 Law & Contemp. Probs. 127.

[xi] Geoffrey Nice, “Who is to blame?” in Transitional justice and human security, supra, (Note 2), p 43.

[xii] At some point, it was felt that the establishment of the International Criminal Court would prolong the Ugandan Conflict. See: Peacebuilding In Post-Cold War Africa: Problems, Progress, And Prospects. Centre For Conflict Resolution, Cape Town, South Africa, Policy Seminar Report, 2009 Number 33, supra.

[xiii] Accra Comprehensive Peace Agreement on Liberia was signed in August, 2003. It set up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) instead of a Court to try the perpetrators. This was later interpreted by the signatories of the CPA as a grant of Amnesty, without which they would not have signed the agreement.

[xiv] Indeed, following the submission of the report of the TRC to the Liberian Legislature, a newly formed group made up of the former war lords, calling itself an association of signatories to the CPA, held a press conference to denounce the recommendations on criminal trials for the war lords, and threatened mayhem if anyone tried to drag them before the courts to face trial.

[xv] Juan Mendez “How to take forward a transitional justice and human security agenda’ in Transitional justice and human security, supra, p.242.

[xvi]Karen Gallagher, Note, No Justice, No Peace: The Legalities and Realities of Amnesty in Sierra Leone, 23 T. Jefferson L. Rev. 149. Abdul Tejan-Cole, supra, (Note 2).

[xvii] Alex Boraine, “Defining Transitional Justice : Tolerance in the search for justice and peace” in Transitional justice and human security,supra, p . E. Gyimah-Boadi, “Ghana’s transitional justice experience” in Transitional justice and human security,supra, p.181.

[xviii] Fatuma Ndangiza, “The role of men and women in rebuilding Rwanda” in Transitional justice and human security,supra, pp170-174.

[xix] Scott Streauss, “Origins and aftermaths. Dynamics of Genocide in Rwanda and their post-crime implications” in After Mass Crime. Rebuilding States and Communities Beatrice Pouligny, Simon Chesterman and Albrecht Schnabel, (eds) United Nations University Press, Tokyo, New York, Paris, 2007; chpt 5, p. 137.

[xx] The Oputa Panel which was a TC

[xxi] Vasuki Nesiah, “Truth vs Justice? Commissions and Courts in Human Rights and Conflict, Julie A Mertus & Jeffrey Helsing (eds) United States Institute for peace press, Washington DC, 2006, p.375. Rev. Bongani Finca, supra, p. 58.

[xxii] Retributive justice focuses on punishment of the perpetrator; and restorative justice is victim-centered as it seeks to rehabilitate or compensate the victim and thereby restore him or her to the position he or she would have been in had the atrocity not been committed.

[xxiii] Truth Commissions and NGOs: The Essential Relationship. The “Frati Guidelines” for NGOs Engaging With Truth Commissions, Occasional Paper Series, International Center for Transitional Justice, New York/ CDD-GHANA, April, 2004, p.1

[xxiv] Contrast the use of two mechanisms, the Special Court and Truth and Reconciliation Commission paid for by the international community through the UN for Sierra Leone whilst the one mechanism urged on Liberia, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was supposed to be funded by the Government of Liberia with its war-straitened circumstances. In the event, the funding was so patchy that it was a wonder they could conclude the work and produce a report at all.

[xxv] Sweden donated a few millions of dollars whilst US gave under a million dollars whilst pledging full support to the process.

[xxvi] Robert Beneduce, “Contested Memories: Peacebuilding and community rehabilitation after violence and mass crimes – A medico-anthropological approach” in After Mass Crime, supra,(Note 17) p.41, at pp.42-44.

[xxvii], Centre for the Study of Forgiveness and Reconciliation, University of Coventry.

[xxviii] Priscilla Hayner, supra,discusses the work of fifteen truth commissions between 1974 and 1994.

[xxix] Brandon Humber, “Does the truth heal: A psychological perspective on the political strategies for dealing with the legacy of political violence” in Nigel Biggar (ed), Burying the Past : Making Peace and doing Justice after Civil Conflict, Georgetown University Press, Washington, USA, 2000.

[xxx] Vasuki Nesiah, supra, at p.378.

[xxxi] Former Deputy Chairman of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and later Chairman of the New York-based International Center for Transitional Justice.

[xxxii] Supra, at p.27.

[xxxiii] Henrietta J.A.N Mensa-Bonsu, “Reconciliation And National Integration.”, in Reconciling the Nation Proceedings of the GAAS/FES Forum on National Reconciliation, FES, Accra, June, 2005.

[xxxiv] Chambers Dictionary, 1982.

[xxxv] Priscilla Hayner, Unspeakable Truths, supra, (Note 1), p.155

[xxxvi] Abdul Tejan-Cole, “The Complementary and Conflicting Relationship Between the Special Court for Sierra Leone and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (2003) 6 Yale Human Rights and Development Journal, 139.

[xxxvii] Vasuki Nesiah, supra, p.378.

[xxxviii] Priscilla Hayner, Unspeakable Truths, supra, (Note 1), p. 8.

[xxxviii] Priscilla Hayner, “Fifteen Truth Commissions 1974-1994: A Comparative Study (1994) 16 Human Rights Quarterly, p.558.

[xxxix] Henrietta J.A.N Mensa-Bonsu “The National Reconciliation Process: The Role of Religious Bodies.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of Catholic Diocesan Priests, Wa, Ghana, January, 2003.

[xl] Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela, “Reconciliation. Co-existence and the building of trust.” in Transitional justice and human security, supra, p79.

[xli] The Liberian TRC made recommendations for lustration of a number of persons including the sitting President. The recommendation was successfully challenged in the Supreme Court by one of those listed for the sanction.

[xlii] Louis Bickford, “Human Rights and the Struggle for Memory”, in Transitional justice and human security, supra, p.136.