Citizenship

When nationality becomes a lifetime wait

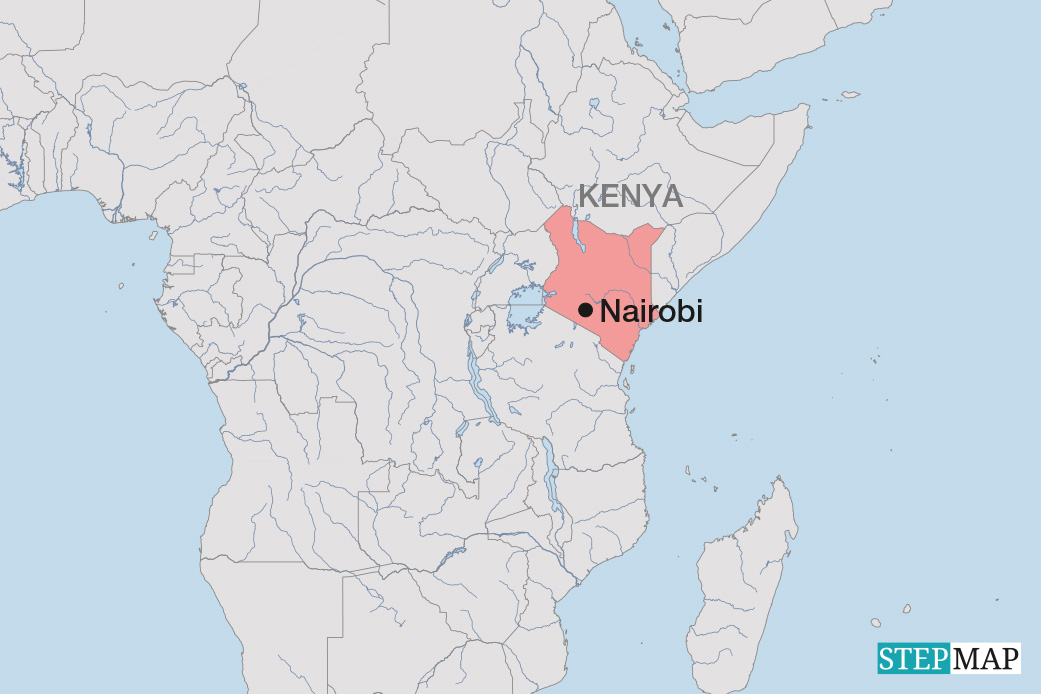

In one of the low-income settlements of the Kenyan capital Nairobi, 26-year-old Fatuma Hassan keeps a well-kept stall selling second-hand shoes. Her business is doing well, but she cannot open a bank account, register a SIM card or travel outside the country. Fatuma was born in Kenya to Somali parents who fled in the early 1990s due to drought. She has lived in Kenya all her life. Yet every attempt to get an ID ends in the same response: “pending vetting.” Her documents have been pending for eight years.

Fatuma says she has visited the local registrar’s office more than a dozen times. Each time, she is asked to bring more witnesses or new letters from chiefs and elders, proofing that she belongs to the community and grew up there. “I gave up,” she says. “Even the people who helped me are tired.” Without an ID, she cannot apply for jobs, register property or even prove her existence to the state.

Across the city, in Nairobi’s largest informal settlement Kibera, 52-year-old Salim Osman faces a similar problem. His parents were Nubians, descendants of soldiers from Sudan who had been brought to Kenya by the British during the colonial era. To this day, many Nubians are denied citizenship.

Salim works as a mechanic. His workshop runs on borrowed licenses. He has tried to apply for an ID five times. Each time, the process comes to a standstill. “They keep saying they are still checking,” he says. “Checking what? I was born here. My father and grandfather were born here.”

In Kenya, there are thousands of people like Fatuma and Salim. Many of them live in informal settlements or border regions, areas where residents typically struggle to have their nationality recognised. Without IDs or passports, they cannot access public services, vote or enrol their children in schools. They live in a country that does not fully accept them and in a system that struggles to define who belongs and who does not.

A continental challenge

Kenya is not alone in this. According to the UN Refugee Agency, millions of people worldwide remain stateless or at risk of losing their nationality – including in many parts of Africa. In Côte d’Ivoire, for example, descendants of migrant farmers still face exclusion from citizenship laws. In Tanzania, some communities of mixed origin have no papers decades after independence. In Zimbabwe, descendants of Malawian and Mozambican labourers have been denied identity cards for generations.

Governments are now under pressure to fix the problem. Civil-society groups are documenting unrecognised populations and lobbying for simpler, fairer ID systems. Kenya has recognised long-marginalised groups, including the ethnic groups of Makonde, Shona and Pemba, as eligible for nationality. Even though Kenya’s President William Ruto promised to abolish extra vetting for residents of the Northeastern region, many Nubians in Kenya still face barriers according to civil-society groups. Sierra Leone has adopted reforms to prevent children from being born stateless. But overall, progress remains uneven. Suspicion and ethnic profiling are still prevalent in ID registration processes. For many people it can take years, and some give up after a while.

According to human-rights organisations statelessness is both a legal and a development issue. Without citizenship, people often cannot access healthcare, education or jobs. They can barely participate in the economy or political life. “Proof of one’s identity is a fundamental right that empowers and protects everyone from systemic discrimination,” explains an activist from Namati, Kenya, an NGO that advances citizenship rights and access to justice. “We call on governments to ensure that everyone is equally documented regardless of their tribe, religion or race.”

Fatuma says she still hopes to get her papers one day. But she no longer expects it soon. “Maybe my children will get them,” she says hopefully. Salim is less optimistic. With a shrug, he says he will keep fixing cars and paying taxes even if the country never recognises him. “I have nowhere else to go,” he says. “This has always been my home.”

Joseph Maina is a freelance writer based in Naivasha, Kenya.

mainajoseph166@gmail.com