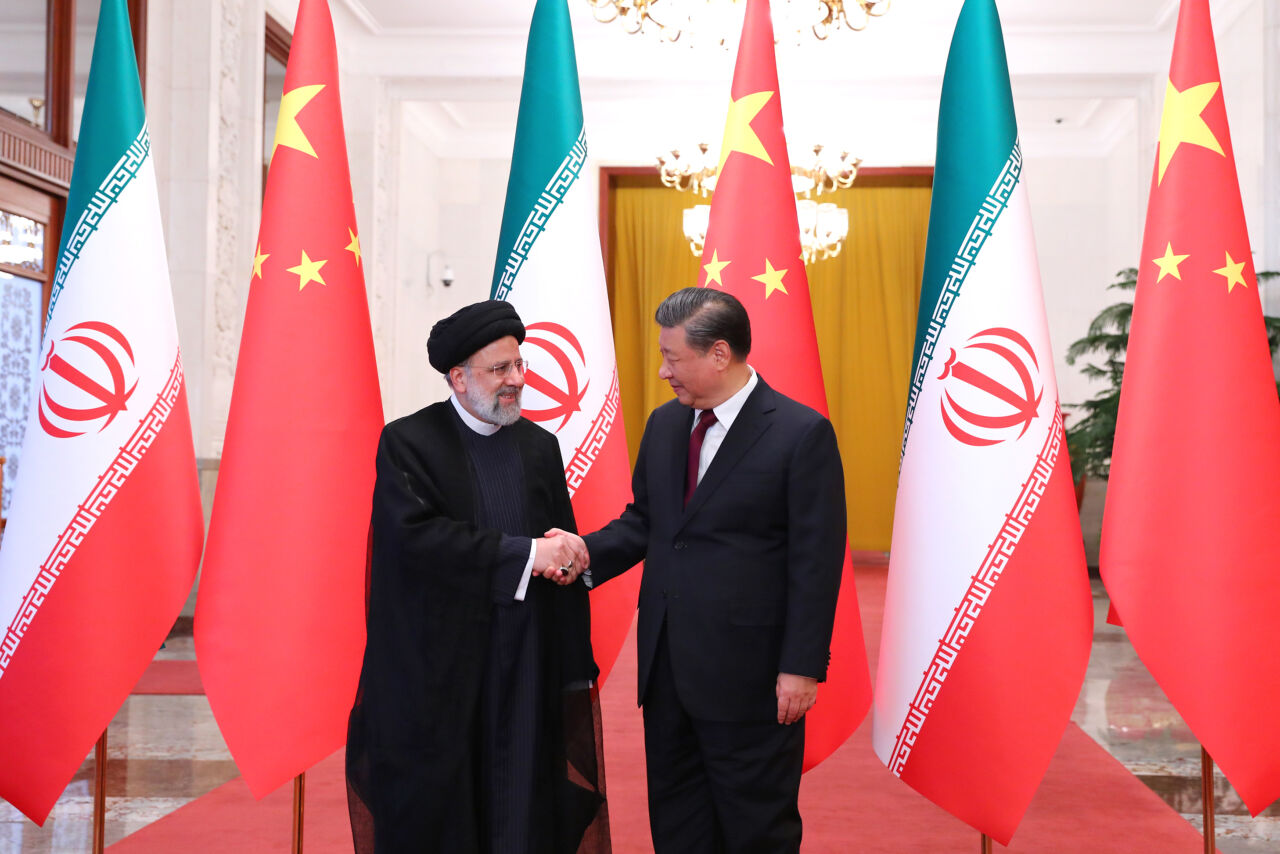

Xi’s Consolidation

China’s leader gets stronger, but his regime gets weaker

Since rising to power in 2013, Xi has fostered a personality cult and worked on rebuilding this country’s system of government in ways that increase the authority of himself, the top leader. The news about the two-terms limit being scrapped fits this pattern. Xi is doing his best to make his rule permanent.

As autocrats tend to do, he will argue that he needs absolute power to ensure peace, prosperity and progress. He is cultivating the narrative of the strong leader who provides what the people need. The implication is that the leader knows what the people need, and that he needs to be forceful because he must control many evil forces that want to harm the people. The personality cult culminates in the claim that whatever is good for the leader is good for the people.

In truth, of course, this kind of supreme leader is accountable to no one. And while they all claim to be serving the people, they enrich themselves, their families and cronies. Unrestrained power means unrestrained scope for abuse. While dictators claim to be strong, however, their strength relies only on suppression. In truth, they fear all kinds of opposition – for various reasons:

- They must look like they are in control at all times because any sign of weakness would undermine their claim to authority.

- They know that many people have legitimate grievances and that public debate of such grievance would reveal that “the people” are not happy.

- Enforcing their will by violence and the threat of violence, they know that their end may be brought about violence too.

Dictatorships promise stability, but they are inherently more fragile that democracies that are supported by a strong institutional order and people’s consent. I assessed the matter in a blog post last year, and the following sentences bear repetition :

“Mao Zedong famously stated that power comes from the barrel of the gun. The philosopher Hannah Arendt convincingly argued that this notion is wrong. Real power stems from the legitimacy a ruler enjoys in the eyes of the people. If people find the government legitimate, they are likely to adhere to its rule. If they are only kept in check by guns, however, their compliance evaporates the moment the threat of violence disappears or is merely reduced. Reasonable regulations are more likely to be accepted than arbitrary orders. Accordingly, rules that result from public debate and democratic deliberation are more powerful than the edicts of dictators.”

Mao Zedong was a totalitarian dictator who caused his people enormous suffering. Millions died during the so-called Great Leap Forward and during the Cultural Revolution. The Communist paradise Mao promised never materialised. China’s economic miracle – and escape from poverty – began under Deng Xiaoping who introduced market competition and provided some scope for personal choice. For good reason, Deng established term limits. He did not introduce democracy, but he did ensure that there were checks and balances within the Communist party.

Xi is now abolishing these checks and balances. Accordingly, trust is being eroded further. If policies are not assessed in thorough debate, mistakes and failures become more likely. If leaders are free to do as they please, personal whims become more important than reasoned arguments. If people fear those in positions of power, they will not speak about what really bothers them and resent will grow without being articulated. Ultimately, this leads to a vicious cycle with lack of trust reinforcing the need for repression which further undermines trust.

Let me end this blog post with a few lines from a comment I published in November (https://www.dandc.eu/en/article/why-dictatorship-less-efficient-apologists-want-us-think). They still make sense:

“Strongman rule will do little to improve China’s socio-economic fortunes. Having masses of people controlled by the secret police is expensive, but does not contribute to a nation’s prosperity. Moreover, oppression discourages every entrepreneur or innovator who does not have a direct mandate from the government. Yet another issue is that, where public debate is hushed up, policymakers only become aware of social or environmental problems very late – if they don’t prefer to suppress bad news entirely. On top of all this, corruption thrives in the lack of checks and balances, no matter how noisily the top leaders may claim to be fighting it. For these and related reasons, despotic rule is actually quite inefficient. However, it does serve one purpose well, and that is enforcing an oligarchic order.”