Governance

Setting the right example

In recent years, peaceful transfers of power have occurred after elections in important ECOWAS member countries, including Nigeria, Ghana and Senegal. The region’s leaders have developed a habit of insisting on their peers’ democratic legitimacy. They also cooperated with the French military to re-establish multi-party democracy in Côte d’Ivoire and Mali after serious crises.

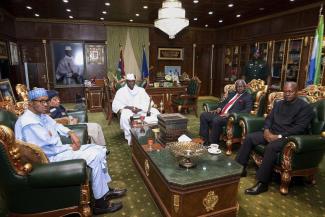

In the past two months, ECOWAS put considerable pressure on Yahya Jammeh, the autocratic president of Gambia, who lost elections in December, but refused to give up power. Facing an imminent military intervention, Jammeh stepped down and opted for exile in Equatorial Guinea.

The determined West African approach is more likely to lead to stability than simply condoning the strongman, as is often done elsewhere in Africa. Stabilising an autocrat’s grip on his country means that discontent and frustration will keep building up since the autocrat’s rule will stay repressive and foster evermore anger. Evermore people will believe that violence is an entirely legitimate means to resolve disputes, and indeed, the only one.

Three things have probably contributed to the ECOWAS stance on democratic principles:

- The civil wars in Liberia and Sierra Leone were interlinked and went on for decades, ultimately dragging in other ECOWAS countries and the UN. They proved that a crisis that traumatises one part of a world region is prone to harm the entire region. Accordingly, it makes sense to prevent – and if need be – contain crises early on. West Africa has had many serious crises, from the Biafra war in Nigeria in the 1960s to the collapse of Côte d’Ivoire early this century to Boko Haram terrorism today. The good news is that leaders now accept that West African problems require West African solutions.

- It helps that many West African countries, and especially the big ones, have been independent for at least 50 years. Two generations have grown up under African governments. The longer a country is no longer a colony, the less sense it makes to blame its problems on foreign powers.

- It probably also helps that most West African countries, and – once again – especially the big ones, became independent without armed struggle. In this world region, France and Britain gradually granted their colonies self-administration, and African leaders then pressed Paris and London into negotiating peaceful transitions to sovereignty. Sadly, this history did not prevent despotic one-party governments, military rule and civil wars. Autocratic leaders, however, could not rely on a militia mindset. In guerrilla warfare, one’s life depends on personal loyalty, and dissent is seen as treason which deserves the death sentence. The longer an armed struggle drags on, the more mafia-like a militia becomes. That is necessary for prevailing in war, but it makes it very hard to move on to pluralistic democracy once the war is over. The leaders of a liberation army are used to absolute command and feel entitled to it, not least because they and their troops sacrificed so much.

West Africa has had its fair share of problems. To the extent that its leaders uphold democratic principles, future crises should prove less traumatic than past ones.